The armored phalanx was of course the supreme weapon of the Greeks. But no weapon alone is sufficient for success. The Greeks knew this from prehistoric times, when they defeated their opponents thanks to the close connection between the various weapons of their armies.

This was also true in classical times. In archaic times it seems that the weight was given exclusively to the phalanx of heavy infantry and the other weapons were sidelined. Of course, areas that traditionally produced cavalry or light cavalry continued in this period to line up lightly armed footmen or horsemen alongside their horsemen.

Thessaly of the Alevids, for example, had many and elite cavalry. In their wars against the Phocaeans (middle of the 6th century BC) the Thessalians achieved great victories against the Poles, in the lowlands. But when they tried to invade the mountainous Phocis, the Phocian slender spearmen, and not the hoplites, overwhelmed them.

The Thessalian cavalry also showed its worth during the first major civil war of historical times, the Lilantian War, between Chalkidos and Eretria. Almost all the cities of central Greece and Athens took part in this war, fighting with one or the other of the belligerents. It is worth noting that, according to a tradition, the use of firearms in this particular war was forbidden, following a common agreement between the warring parties.

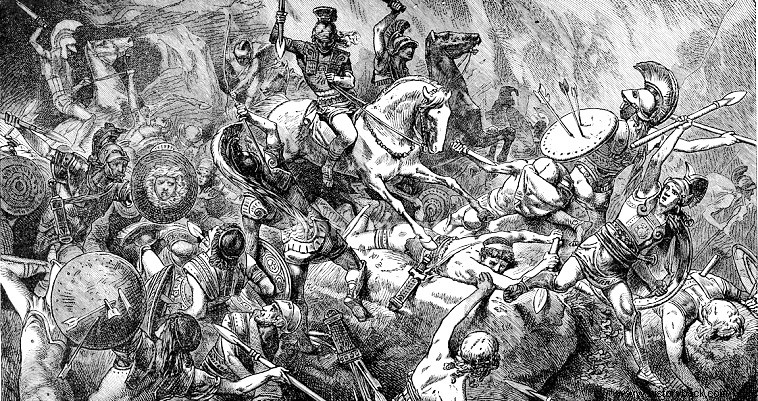

On the field of battle, however, the cavalry was only an auxiliary weapon, in contrast to the striking role it had in the Minoan and early Mycenaean armies. His mission was to cover the flanks of the friendly phalanx, to overturn the opposing light infantry who were possibly harassing the friendly hoplites, to advance the phalanx by reconnoitering and clearing the ground, and to pursue the defeated enemy.

It was therefore, due to mission and regardless of armour, light cavalry. However, the majority of horsemen did not carry breastplates. The horsemen were armed with a number of javelins and swords. Later, heavier cavalry was formed, whose men wore helmets and breastplates. They also carried the same equipment as the light horsemen, but with the addition of a short spear.

Only the Macedonian heavy cavalry, as early as the 6th century, were real shock cavalry, whose men did not carry sidearms but long lances 3-3.5 meters long, the xyston . In southern Greece, due to the morphology of the terrain, the development of cavalry was not favored.

Great Athens fights at Marathon without cavalry. But even at Plataea the Greek allied army lacks cavalry support. After the alfalfas, the cities of southern Greece developed a small number of cavalry divisions. The Athenians formed a division of 1,000 light cavalry and 200 horse archers.

Sparta theoretically had a cavalry division of 300 men, whose men formed the royal guard – Leonidas' 300 who fell with him at Thermopylae. But these men never fought on horseback. At best they acted as mounted infantry, using horses to move faster, but always fighting on foot.

Only in the middle of the 5th century BC. Sparta developed its first real cavalry division, 400 strong. The cavalry was arranged by islands in square formations similar to the phalanx, with a relatively large depth of up to 8 yoke.

The Thessalians were the first to invent the rhomboid formation, a formation that gave cavalry tactical flexibility by allowing rapid engagement, but also disengagement and retreat in any direction. At the four corners of the rhombus were the hilarchos at the top, the bodyguards at the sides and the tails at the back.

All four were officers. Their placement at the four corners of the rhombus allows excellent control of the clay and maintaining its cohesion. Later Philip of Macedon invented the emboloid formation, known as the wedge, which was nothing more than a development of the Thessalian rhomboid formation.

The wedge could be simple – an isosceles triangle with the apex towards the enemy – or double – a flattened rhombus. The hilarchos took their place at the top and the bodyguards at the sides. The base of the wedge was formed by an odd number of horsemen.

The number of horsemen per yoke decreased with each yoke approaching the top of the wedge. The wedge was an offensive formation par excellence, ideal for use by shock cavalry such as the Macedonian Companions, whose men also carried the appropriate weapon for its exploitation, the long lance.

The cavalry in the times under review undertook, as already said, auxiliary missions of the phalanx. Under normal conditions, cavalrymen were not capable of prevailing, without the assistance of friendly infantry, against an enemy division of heavy infantry.

But they were able to inflict losses on it, to delay it, but only this one was losing its coherence to defeat it. An exception was the Macedonian cavalry, which, thanks to its weight and speed, was able to break up, not easily, the phalanx of hoplites. Chariots, finally, seem to have been kept in service until the 6th century.