Civil wars were an endemic phenomenon in ancient Greece, in all its historical phases. Before the royal house of Mycenae dominated Greece it had to fight hard against the other Achaean kingdoms, the Peloponnese first, and the rest of Greece later. The myths of Herakles, national hero of the Mycenaeans, born in Thebes and forefather of the Dorians (the Heracleids), are enlightening on this point.

The myth about the cleaning of the stables of the king of Ilia, Augeas, is related to the Mycenaeans' war against the Ilias, which ended with the victory of the former. The royal dynasty of the region was dethroned and the country passed under the "guardianship" of Mycenae.

In commemoration of his victory, legend states that Hercules then established the Olympic Games. Having secured control of the northern Peloponnese, the Mycenaeans turned against the Messenians. The Messenians were defeated and their king Nileas was killed. His youngest son, Nestor, ascended the throne in his place.

All that remained was the conquest of Laconia. This was achieved with the assistance of the Arcades. And here the old dynastic house of Hippo was overthrown and Tyndareos, a close friend of Herakles, took over as king. The subjugation of the entire Peloponnese under the scepter of the king of Mycenae, Eurystheus, was now a fact. Essentially, this development is estimated to have been achieved at the beginning of the 13th century BC.

Both Apollodorus of Rhodes, and Pausanias, make extensive reports about these events, considering them completely true. Regardless of whether their mythological descriptions were accurate, it is important that they describe wars that actually took place and that led to the declaration of Mycenae as the first Peloponnesian power. From there, however, competition began with the other ancient and powerful city, Thebes.

Thebes in the 13th century BC. was the most powerful city, head or member of a coalition of cities in central Greece. The city was probably ruled by a king of the Minyan house. The Minyas were probably an Ionian race, i.e. they were racially related to the Mycenaeans and are connected to the first Neolithic civilizations of Sesklus and Dimenius.

The leader of Jason's Argonaut Expedition was Minyas by birth, but most of their Argonauts were Mycenaeans. Both Herodotus and Apollonius of Rhodes speak of the house of the Minyas.

According to Herodotus, the inhabitants of Lemnos were also Minyas. From 2,000 BC the house of the Minians controlled Boeotia, part of Magnesia, Phthiotida and Phocis with the Boeotian Orchomenos as its center. Until the 13th century BC this state was strong enough to defy the omnipotence of the Mycenaeans. The two coalitions acted and functioned in competition with each other and thus the conflict did not take long to break out.

This war should be considered the first historically recorded war that took place in Greece. Homer gives us in his epics many facts about him. The reasons that led to the outbreak were dynastic and of course economic.

Tradition states that the occasion was given when Adrastos, king of Argos, helped his son-in-law Polyneices against the brother of Eteocles, son of Oedipus. In the meantime, at about the same time, equally important events were also taking place in the Peloponnese.

After the death of Heracles, the king of Mycenae Eurystheas expelled the descendants of the hero from the Peloponnese. They, led by Hyllos, fled to Athens. When Eurystheus campaigned against Athens, he was defeated by the combined army of the Heraclides and the Athenians, near Megara, and was killed.

Thus the dynasty of Perseus disappeared from Mycenae, on whose throne Atreus now ascended (about 1280 BC as evidenced by evidence of destruction at Mycenae). The Heracleians finally fled to Thebes. Since then at regular intervals they would attempt to return to their ancestral land. The first time they attempted it they were defeated and Hyllos was killed.

To prevent their further descent, Atreus fortified the Isthmus (around 1,250 BC), as evidenced by the remains of Cyclopean fortifications found in the area. So when Polyneices claimed the throne of Thebes, the Peloponnesians found the golden opportunity they were looking for and attacked Thebes.

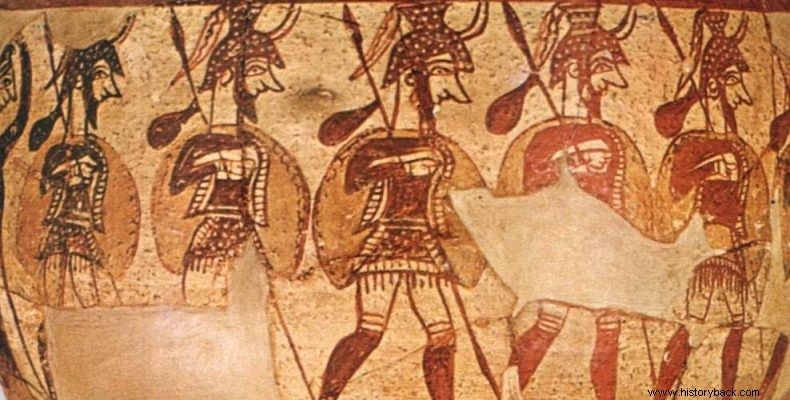

Argios Adrastos was placed at the head of the operation. Arcadian and Aetolian troops also took part in the operation. The Peloponnesians arrived before Thebes and asked the Thebans to grant their demands. But their proposal was not accepted and the war began. The Peloponnesian forces attacked but were repulsed. Then the Thebans, with the help of their Phocian and Orchomenian allies, counterattacked.

However, in the battle fought on the Ismenian hill, near the city, the Thebans and their allies suffered a crushing defeat and their forces withdrew within the walls. The Peloponnesians then attacked the city again but were again repulsed and two of the leaders of the army, Kapaneus and Amphiaraos, were killed. A duel ensued between the two brothers, Eteocles and Polynices, in which both were killed and the conflict remained inconclusive.

The Peloponnesians continued the fruitless and bloody attacks until the rest of the leader, except Adrastos, was killed. The latter abandoned the siege and returned to the Peloponnese, after first asking the king of Athens, Theseus, to demand the burial of the Peloponnesian dead, which the new king of Thebes, Creon, had ordered to remain unburied.

Indeed, Theseus pressed the Thebans and received and buried the dead Peloponnesians. Thus ended the campaign of the "Seven on Thebes", with a defeat for the Peloponnesians, but not so overwhelming as to give the Thebans the right to attempt an invasion of the Peloponnese.

But the Peloponnesians persisted and a few years later they repeated the attack against Thebes. This time the operation was led by the descendants of the dead leaders of the first operation, all of whom later participated in the campaign against Troy. The "Campaign of the Descendants", as it was called, brought the desired result. The united armies of the Messenians, the Corinthians, the Megarians, the Arcadians and the Argives defeated the Thebans in the battle of Glisanta and took control of the city.

After the final victory of the Mycenaeans and in this cruel and long war, the successor of Atreus, Agamemnon, remained the absolute ruler of all southern, central and western Greece. Another important result of the Theban defeat was the flight of the Heraklides further north. Later when, after the long Iliadic (Trojan) War, the power of the Mycenaeans weakened, the Heraklideans will return to their homeland, contributing, unintentionally, to the creation of the myth about the "descent of the Dorians".