On the first day of December 1912, the weather had improved. The Greek destroyers were still patrolling the entrance to the Dardanelles straits, awaiting the exit of the Turkish fleet. The information said that the Turkish fleet was preparing to leave its shelter.

On December 1st, the Greek destroyers "Sphendoni", "Langhi" and "Navkratousa", which were patrolling in front of the straits, perceived an enemy destroyer exiting them. Immediately "Sphendoni" and "Longhi" sailed against him with all their might and from a distance of 3 km opened fire on him.

The Turkish destroyer eventually escaped and returned to the safety of the straits. A little while later, however, the cruiser "Menjitier" appeared.

The Greek destroyers signaled Kountouriotis and hurried to engage the enemy cruiser. "Menjitier" fired over 100 shots. But none found the target. In the meantime, Kountouriotis had ordered the departure of the fleet from Moudros.

He was sure that the cruiser was a precursor of the Turkish fleet, which would finally go out to fight in the open sea. But the Turks again disappointed him. After "Menjitier" exchanged fire with the Greek destroyers for some time, it turned back again and entered the straits.

The Greek admiral, however, correctly interpreted the events as preliminary moves by his Turkish counterpart, which were intended to "read" the Greek reactions. The signs indicated that the exit of the enemy fleet was imminent.

With this rationale, the Greek admiral remained all night of December 1st to 2nd in front of the straits, at a distance of only 6 km from the coastal forts. And the next day, however, the Greek fleet was patrolling in the same area.

Shortly before nightfall, only Kountouriotis moved the fleet south, initially towards Lemnos, in order to mislead the enemy. But as soon as darkness fell, the fleet changed course and moved north again, sailing past the coast of Imbro.

Little by little the light of day began to overcome the winter darkness. December 3rd was dawning. Greek ships were still plying the same monotonous route between Imbros and Tenedos. Suddenly the half-asleep Greek crews woke up abruptly. Word of mouth spread the joyful news.

"Columns of smoke from the Dardanelles. The Turks are coming out." A feeling of relief overcame every man of the Greek fleet, from Kountouriotis to the last sailor.

In a production line, the cruiser "Menjitier" and three destroyers were sailing towards the exit of the straits. Before long they were out and heading south. From the narrows, however, other columns of smoke could now be seen. It was the Turkish battleships that were sailing in turn towards the exit.

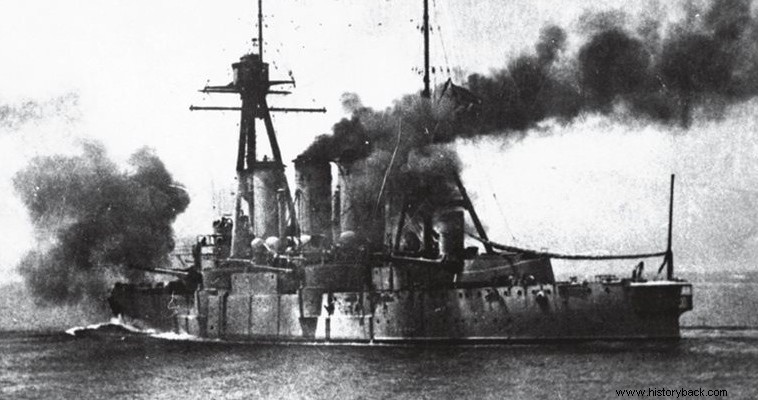

Leading the way was the flagship Hayredin Barbarossa, on which Admiral Ramiz Pasha was aboard. Also following in the production line were "Turgut-Reis", "Mesoudie" and "Asar-i-Tefiq".

The "Barbarossa" and "Turgut-Reis" were very powerful ships, each with six 11-inch (280mm) guns, being, in theory, capable of sinking the entire Greek fleet alone.

At 09.00 the two fleets were directly opposite, one from the other, at a distance of 14 km still prohibitive for the execution of fire, with a chance of success. From the bridge of "Averof" Kountouriotis observed the enemy movements. With his cross of Holy Wood hanging around his neck, the admiral addressed his crews with the order of the day.

"With the help of God, the wishes of our King, and in the name of justice, I sail with unyielding momentum and with conviction towards victory, against the enemy of the nation. Kountouriotis s ».

At the same time, the admiral was shouting from the bridge to the sailors of "Averof":"Our time has come, guys. Remember the sailors of '21. We will crush the infidels. God is withus ». Immediately afterwards the admiral came down from the bridge and together with the ship's priest, Archimandrite Daphnos, turned the whole ship around, encouraging his men.

The time was 09.22 when two flashes were seen from the fore tower of the "Barbarossa". The other Turkish battleships followed his example. A few moments later the Greek ships also responded. The Turks scored non-stop and particularly densely, but also particularly misplaced. On the contrary, the fire of the Greek ships was slower but also more accurate. After an exchange of fire for about 10 minutes, the first fires became visible on the Turkish battleships.

The distance that separated the two fleets was constantly decreasing. Kountouriotis from the bridge of "Averof" continued to direct, completely uncovered, the race. In vain his officers begged him to enter the armored compartment of the bridge and direct the battle from there.

He remained unperturbed in his place. Suddenly Koundouriotis , realizing that the stay of "Averof" in formation did not allow him to make the most of the ship's potential, made the historic decision, which also determined the fate of the conflict.

Leaving the command of the squadron of old Greek battleships to the captain of "Spetsai", Captain Ginis, Koundouriotis ordered the famous "Z" sign to be raised on the mast of the flagship .

In this way the admiral declared his intention to move with "Averof" independently. "Barba-George" roared as the "boilers" began to be fed with more and more coal. The "Averof" was now sailing at a speed of 20 knots.

The purpose of Kountouriotis was no other than to be at the top of the Turkish line, while the other three Greek battleships would attack him from the side.

At 09.55 "Averof" was located exactly perpendicular to the axis of navigation of the Turkish battleships. His guns were constantly fired at the advancing "Barbarossa," from which jets of fire were constantly shooting out.

But the other Turkish ships were also receiving a barrage of fire from the Greek battleships and scouts. Attacked from all sides, the Turkish admiral realized that if he did not retreat soon into the straits, his fleet would decorate the bottom of the Aegean with the carcasses of ships.

He was therefore forced to order a change of course towards the straits. However, his signal, in the midst of the battle, was misinterpreted, as a result of which the Turkish faction lost all cohesion.

In the face of the ensuing chaos, the frustrated Turkish Admiral Ramiz ordered his ships to sail independently towards the straits. Kountouriotis, seeing the disintegration of the Turkish formation, ordered the attack of the destroyers against the enemy.

Unfortunately, however, the radio antenna of "Averof" had been destroyed by enemy fire and, luckily for the Turks, the signal never reached the Greek destroyers. Annoyed then, the admiral decided to confront the Turkish fleet alone, with "Averof", the "Seitan Papor", as the Turks called it.

The sight was truly unique. A single ship single-handedly pursued an entire fleet. All Turkish vessels and shore guns fired incessantly against the Averof ». However, their fire was tragically wrong and the lucky "Barba Giorgos" escaped.

Despite the pursuit of "Averof", however, the Turkish ships managed to enter the straits, even if they were on fire. The naval battle had ended with the complete predominance of the Greek fleet. It had lasted just 63 minutes of the hour. With his band frolicking in the stern, the Averof finally turned west, abandoning his prey.

During the "Naval Battle of Hellas". » the Greek fleet suffered minimal damage. A single man was killed and eight wounded. Unfortunately, one of the wounded, Lieutenant Mamouris, died a few days later from an infection of his minor wound.

No Greek ship suffered any significant damage. Even the "Averof", which bore the brunt of the fight alone, had minimal damage to the bow bulkhead.

On the contrary, the Turkish fleet had suffered serious damage and serious losses. More than 100 men had been killed and as many wounded. "Barbarossa" suffered the most serious damage. The rest of the Turkish battleships had minor damage.

The fleet's victory in the Battle of Hellas was widely celebrated throughout Greece. Strangely, celebrations were also held in Constantinople. Turkish newspapers, apparently at the behest of the government, competed with each other in publishing the most obscene monstrosity. So some of them assured their readers about the sinking of "Averof" at the entrance of the straits.

Still others described in vivid colors the sinking of the "Averof" 70 n.m. from Piraeus, to whose port it was towed, after the serious damage it had suffered in the naval battle. Finally, they made a reason for disorderly retreat and crash of the entire Greek fleet! If nothing else it was a serious attempt to convince themselves.