The Spanish transition, understood as the period between the death of Franco on November 20, 1975 and the electoral victory of the PSOE on October 28, 1982, was characterized by the transition from a dictatorial political regime to a democratic one. This course was channeled through pacts and negotiations between the Francoist forces and the democratic forces. Every negotiation is the product of a relationship of forces:the Franco regime had all the institutional support and a part of the population, sociologically aligned with the regime; the opposition had democratic legitimacy, international support and a very active, albeit small, base. The continuity of the Franco regime was impossible and the implantation of a democracy without counting, at least, with the opening sector of the regime was not feasible either. Hence the need for a convergence between the aforementioned Francoist sectors and the main opposition forces. Some based their strength on the control of State institutions, others on important popular mobilizations.

It has been wanted to present this process as a model in terms of the transformation of a dictatorial regime into a democratic one. Emphasis tends to be placed on the capacity of those political leaders for negotiation, but the Transition was far from being an exemplary and peaceful process. The degree of political violence that it produced was much higher than that which occurred in Portugal with the Carnation Revolution –April 25, 1974– and the subsequent revolutionary process, where there were no fatalities; and it was also much higher than the one that occurred during the fall of the Greek Colonels' Dictatorship on June 24, 1974, where there were less than a dozen fatalities and all of them in events that occurred later.

The democratic transition process has recently been questioned, blaming it for some of the current problems of Spanish democracy. This accusation doesn't make much historical sense; To demand more forcefulness from the democratic forces of that time in the negotiation processes that were carried out is to misunderstand that historical situation. Although very weakened and with little or no international support, Francoist sectors that were recalcitrant to any change continued to control, to a considerable extent, some not inconsiderable sources of power:the judiciary, law enforcement, the armed forces, etc., which sometimes acted with total autonomy from the government. . They also had another element that permeated many Spanish social sectors:fear, fear of repression by the regime, fear even of a military coup –Tejero and others in 1981–, and fear of a new civil war. That fear prevented popular mobilizations from reaching sufficient strength to bring about the fall of Francoism. The uncertainty about what might happen also favored moderate options.

The difficulties of that historical situation are shown in the extreme violence that characterized the period. Paloma Aguilar and Ignacio Sánchez Cuenca recorded 665 deaths as a result of political violence between 1975 and 1981. The breakdown of the figure shows the origin of these deaths:

- State repressive action:162 deaths, 24%.

- Actions by nationalist terrorist groups:361 deaths, 54%.

- Actions by far-left terrorist groups:67 deaths, 11%.

- Actions by far-right terrorist groups:57 deaths, 10%.

There was therefore, in the Transition, a confluence of forces that opted for the practice of political violence, of terrorism in short. The police repression, directed by commanders who came from the Franco regime, was oriented against the left, and it is true that it aggravated the conflicts but it was not a driving force behind terrorist violence. The groups that practiced it had their own objectives, independent of the police action:independence of some territory, reaction to the actions of ETA or intimidation of the left -in the case of the extreme right-, blows against the dominant classes (businessmen, military,…) by the extreme left. Their actions, regardless of their casuistry, contributed to social and political instability and encouraged the moderate forces of the Franco regime and the opposition to converge to stabilize the political system.

One of the most paradigmatic examples of this terrorist violence was the so-called Atocha massacre. On January 24, 1977, three extreme right-wing gunmen entered a labor law office located at 55 Atocha Street in Madrid. The members of that office were linked to the CC.OO union. and with the PCE, still illegal. The result of the assault was five people dead – Enrique Valdevira, Luis J. Benavides, Francisco J. Sauquillo, Serafín Holgado and Ángel Rodríguez – and four injured. It was a full-fledged provocation to the communist left to induce a reaction that would make its legalization and inclusion in the new democratic system difficult or impossible.

The context of this terrible action is part of the reaction of the extreme right to the release of Santiago Carrillo. He had been in Spain illegally since February 1976 and had been arrested in December of that year and released shortly after. Days before the attack there had been two deaths of people linked to the left – one assassinated by Triple A and another hit by a can of smoke in a demonstration –, an office of the UGT in Madrid had also been assaulted, which was found empty at that time.

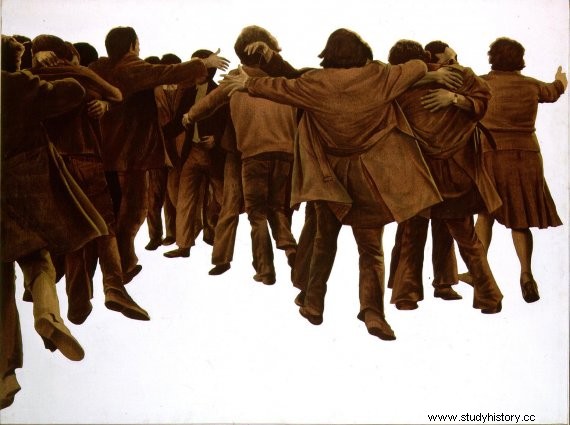

The response of the PCE and the left in general was far from what was expected by the reactionary forces. The burial of the Atocha victims became a massive demonstration that passed without incident; solidarity with the victims spread throughout the country through strikes and other acts. The Communist Party showed its restraint and this undoubtedly favored its legalization during Holy Week of that year –April 9, 1977–.

This time the government was not going to remain impassive in the face of the slaughter. The priority for the police was the capture of the assassins; this was essential to give credibility to the democratization process that was taking place. They had not fled, relying on their political and police contacts. The Armed Police arrested them a few days later, revealing that they were all related to the Falange Española or Fuerza Nueva. Further investigations also brought to light the likely involvement of the so-called Gladio network, an Italian far-right organization.

The Atocha massacre marked one of the milestones of political violence during the Transition. It was an example of how the most reactionary sectors of the Franco regime, still powerful, tried to prevent, by all means, any process that would lead to the establishment of a political democracy. We have already seen that they were not the only ones and that other nationalist or extreme left forces were also involved in making this project difficult. For all these reasons, it was a complicated process that finally gave way to a democratic system, imperfect without a doubt, but the result of the relationship of political and social forces that existed at the time.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.

Alvarez, L. (2011). The sewers of the transition . Madrid:Espasa.

González Sáez, J. M. (2012). The political violence of the extreme right during the Spanish transition (1975-1982) Proceedings of the III International Congress on the History of Our Time . Logroño:University of La Rioja.

Julia, S. (2014). Still the Transition! THE COUNTRY .

Kornetis, K. (2011). The Greek and Spanish democratic transitions in retrospect. In C. L. Frias, Jose Luis; Rodrigo, Javier (eds.) (Ed.), Reevaluations. Local stories and global perspectives. Zaragoza:Ferdinand the Catholic Institution.

Nerín, G. (2016). The Spanish transition:a democracy of blood and lead. The National . Retrieved from http://www.elnacional.cat/es/cultura-ideas-artes/xavier-casals-transicion-espanola_104653_102.html

Redero, M. (1994). The Spanish transition. Notebooks of the Current World, 72 .

Sanchez Cuenca, I. (2009). Terrorist violence in the Spanish transition to democracy. History of the Present, 14, 11 .

Sotelo, I. (2013). The myth of the Consensual Transition. THE COUNTRY .