According to the 2018 Barometer of Reading Habits and Buying Books, the number of book readers in their spare time reached 61.8% of the population. The number of frequent readers also grew, those who read at least once or twice a week, which now account for 49.3% of the population. 38.2% of Spaniards never or almost never read. Although the trend is upward, these figures do not exactly place us at the head of Europe. Regarding the consumption of wine, the quintessential product of taverns, the data shows that the consumption of wine per person per year is 21 litres. This figure places us very far from France or Italy, also large producers but better consumers, since their rates are 47 n and 37 litres/person/year, respectively. As can be seen, also in wine, as in reading, we are much more producers than consumers. Understanding, of course, that both wine and books are an important part of our culture.

But I have not come today to talk about the consumption of books or wine, at least not about the current situation; but that books and wine are the pretext to show them how the relationship of the Spanish with books and with wine goes back a long way, as evidenced by the edifying anecdotes of some of the great classics of Spanish literature, related to wine , the taste that some of them had for him and how they "reproached" each other.

But first, let me provide some more data:according to data from the Spanish Economic Yearbook According to La Caixa, in Madrid there were almost 18,000 bars and restaurants in 2013, out of an estimated population of 3.3 million inhabitants; and, according to the census carried out by the Spanish Confederation of Guilds and Associations of Booksellers, in 2013 there were 4,336 bookshops in Spain. The aforementioned Census of Bookstores gives the Community of Madrid 517 bookstores, third position in the ranking by autonomous communities, behind Andalusia and Catalonia. Therefore, Madrid in 2013 had 18,000 bars and 300 bookstores.

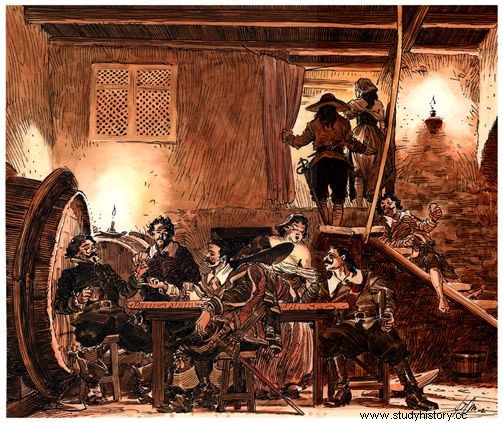

And Madrid at the beginning of the 17th century? 391 taverns in front of 1 bookstore.

Néstor Luján tells in Daily life in the Spain of the Golden Age :

in 1600 there were no fewer than 391 taverns in Madrid, according to the chronicles of the time.

And the people, echoing their number, recited, almost without hyperbole, the epigram

Madrid is a brave city

that between ancient and modern

has three hundred taverns

and a single bookstore.Let me add, just in case, that brave , said of a person, refers to having rustic customs due to lack of good manners or people treatment.

The generous rounding "down" of the epigram (from 391 to 300) is surely a metric requirement that does not ruin such tasty octosyllables. I do not know the accuracy of these data and if the epigram is a kind of satirical joke that in the Golden Age highlighted the great fondness of the Spanish for wine compared to culture, including in the lot some of the great classics of our literature . Numerous municipal regulations exist from those years that show how wine was a fundamental element in the commercial activity of the city, including convents, which competed shamelessly in the production and dispatch of such a precious element, and the bitter disputes that bartenders and monks kept about it. I know that times have changed, that literacy and access to culture have improved a lot, but our love of wine seems to go back a long way.

The literature of the time treats innkeepers very badly. The most common accusations, those of watering down the wine, selling it full of mosquitoes and dealing with it. You probably know the origin of the word “tapa ”, today associated with a small portion of food that accompanies any drink consumed in a tavern, but which originally had the textual function of “covering” the glass of wine with a piece of bread or ham to prevent insects of all kinds from falling inside. . It is clear that Tirso de Molina was concerned about the issue because he states:

When I ask for a drink, they bring me water in the glass and they pour wine on me.

And on another occasion:

Here they call innkeepers

and they go about baptizing lambs.

Lope de Vega also reflects on the question:

Because in wines in Madrid

the same is water as wine…

no matter how many fountains you make

the more you have in the taverns.

And lashes out at the bartenders and their sinful morning rush:

When the road boy

throws barley to the mules

and the thieves with bulls

water down the milk and wine.

Rojas Zorrilla also parodies the situation when one of his characters shows a spell to transform water into wine, in the style of the Wedding at Cana, and another replies:

If this is wine from Madrid

it will be just as watery as before.

Although these verses were aimed more at expressing dislike for the bartenders than at criticizing the benefits of wine, which they did not hesitate to praise when they had occasion. It is Quevedo who made this declaration of intent:

He said to the frog the mosquito

from a jar:

"It is better to die in the wine

than to live in the water."

And it is clear that he did not care too much that the wine had mosquitoes, as he declares in his sonnet He drinks precious wine with mosquitoes inside:

Nits of the vintage, I admit you

In my throat because you have as a rope

The grandson of the vine, blessed liquor.Take the vogue towards my walnut,

That by drinking you all, I take it out on you

The wine you drank and it drowns you.

And it is once again Lope de Vega who affirms:

The older wine gets, the hotter it is:contrary to our nature, the longer it lives, the colder it gets.

Literary disputes have been common among our pens. Some brilliant, others pitiful. In his good judgment, he allowed the darts that Pérez Reverte and Umbral dedicated to each other to be qualified in one way or another; those that Cela received from various fronts; or the joke that Valle Inclán dedicated to José Echegaray, when he sent letters to a friend who lived on the street that were dedicated to the Nobel Prize winner and put in the address “ street of the old idiot ”. The letters arrived, hey.

Although it must be recognized that the most meritorious are those exchanged by Quevedo and Góngora, on the one hand, and Cervantes and Lope de Vega, on the other. They were the ones who raised the insult to the category of literature. But our classics not only held literary jousts, but, as an active part of 17th century society, they also reproached each other for their fondness for wine and questioned the merits achieved by their rivals, attributing them to the excessive intake of the grape derivative. Almost all the great Castilian classics, from Quevedo to Lope de Vega, had a reputation for not disgusting good wine, to the point of being described as drunk by some "envious" contemporaries. When the Lord of La Torre de Juan Abad received the Encomienda from Santiago, Góngora wrote about it:

It is due to San Trago and not to Santiago,

And in other delicious verses Góngora himself attacked the two great literary enemies of his, with this witty diatribe:

Today they make a new friendship

more because of Bacchus than because of Phoebus

Don Francisco de Que-bebo

and Félix Lope de Beba.

But as where they give them they take them, Góngora also received his. Apparently he wasn't disgusted by wine either, so his alter ego Quevedo gave him a tasty barrage by referring to him as " Priest of Venus and Bacchus ”

Surely everyone spoke from their own experience. And the "tradition" of associating literary creativity with the intake of alcoholic beverages has survived to this day in the most diverse variants. But I cannot end without advising you not to forget to follow the wise advice that the classics wrote about wine. As Quevedo himself said:

To preserve health and collect it if it is lost, it is advisable to extend the use of drinking wine in everything and in all ways, because it is, in moderation, the best vehicle of food and the most effective medicine.

And in the mouth of Don Quixote, Cervantes recommends Sancho Panza about his love of wine:

Be temperate in drinking, considering that too much wine does not keep a secret or keep a word.