On March 18, 1962, the agreements were signed in Evian who are going to put an end to this war which does not speak its name, the war in Algeria. The representatives of the GPRA and the French government agree to put in place an immediate ceasefire (taking effect on March 19). The Evian agreements also include political and military clauses, which open up the possibility of Algerian self-determination. However, we can ask ourselves the question:have these ultimately poorly known but highly disputed agreements been applied?

On March 18, 1962, the agreements were signed in Evian who are going to put an end to this war which does not speak its name, the war in Algeria. The representatives of the GPRA and the French government agree to put in place an immediate ceasefire (taking effect on March 19). The Evian agreements also include political and military clauses, which open up the possibility of Algerian self-determination. However, we can ask ourselves the question:have these ultimately poorly known but highly disputed agreements been applied?

The context of the negotiations

Since the year 1961, the Algerian war has increased in intensity and nature with the creation of the OAS, following the referendum on the self-determination of Algeria . Violence was at its peak, and France was on the brink of civil war after the putsch of Generals Jouhaud, Salan, Zeller and Challe in April 1961. The GPRA negotiated with the government, while the FLN organized demonstrations and attacks in metropolis. This leads to tragedies like October 17, 1961, during the bloody repression by the police of Maurice Papon of a demonstration of Algerians in Paris. The OAS, for its part, also multiplies the attacks.

Their number increased at the beginning of 1962, and De Gaulle tried to put their importance into perspective, while ordering punishment for the members of the OAS. On February 8, 1962, a demonstration by unions and left-wing parties against “the fascist danger” was harshly repressed by the police and left eight dead at the Charonne metro station.

This does not prevent the new Evian conference from opening on March 7, 1962; it resulted in the Evian Accords on March 18, 1962.

The Evian Accords (March 18, 1962)

The culmination of two years of difficult exchanges, the Evian agreements are made up of 93 pages and 111 articles, and cover several areas, military and political. The agreements were prepared upstream, during February 1962 (after Charonne), at Les Rousses, in the presence on the French side of Louis Joxe (Minister of Algerian Affairs), Robert Buron and Jean de Broglie; and on the Algerian side, Krim Belkacem (vice-president of the GPRA), Lakdar Ben Tobbal, M'Hamed Yazid and Saad Dahlab.

The first part deals with the conditions of self-determination of Algeria, and its relations with France ( economic aid and cultural cooperation, for example). The second part must settle past disagreements, in particular on the French in Algeria, the majority of whom are supposed to be able to stay in the country that has become independent. The case of the Sahara is also discussed, and France retains its economic interests there and the right to carry out nuclear tests there for five years. On the military side again, France keeps under its control the naval base of Mers-el-Kébir for another fifteen years. The last part of the Evian Accords finally fixes a ceasefire at noon the next day, March 19, 1962, and guarantees the property rights of the French in Algeria.

The first part deals with the conditions of self-determination of Algeria, and its relations with France ( economic aid and cultural cooperation, for example). The second part must settle past disagreements, in particular on the French in Algeria, the majority of whom are supposed to be able to stay in the country that has become independent. The case of the Sahara is also discussed, and France retains its economic interests there and the right to carry out nuclear tests there for five years. On the military side again, France keeps under its control the naval base of Mers-el-Kébir for another fifteen years. The last part of the Evian Accords finally fixes a ceasefire at noon the next day, March 19, 1962, and guarantees the property rights of the French in Algeria.

The application of the Evian agreements

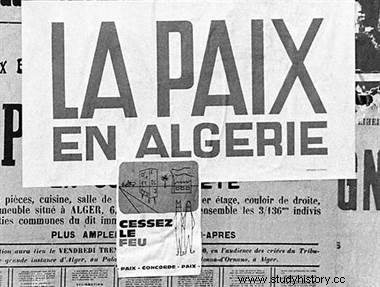

As expected, the ceasefire was proclaimed on March 19, 1962:it was peace. Normally. the French government put up posters proclaiming “Peace in Algeria” and announcing the ceasefire on the walls of Algerian towns and villages. However, the agreements are quickly challenged and denounced. First of all by the OAS which, from March 21, designates in a leaflet the French forces in Algeria as “occupying forces”. In the following weeks, the violence escalated and the French in Algeria began to leave the country, against the instructions of the OAS, which decided to apply a scorched earth policy.

But the Evian Accords are also contested on the Algerian side. Indeed, the winners of the war opposing the various factions of the GPRA which, in the summer of 1962, came to power in an independent Algeria since July 3, were opposed to what they considered to be neocolonialism. Most of the provisions are "revised", and Algeria turns to foreign aid workers, particularly from the Soviet bloc, and begins a policy of Arabization.

But the Evian Accords are also contested on the Algerian side. Indeed, the winners of the war opposing the various factions of the GPRA which, in the summer of 1962, came to power in an independent Algeria since July 3, were opposed to what they considered to be neocolonialism. Most of the provisions are "revised", and Algeria turns to foreign aid workers, particularly from the Soviet bloc, and begins a policy of Arabization.

The results of the Evian agreements are therefore mixed, because of the context of violence and the policy of the new Algerian power. They nevertheless enabled the end of the war, and paved the way for the independence of Algeria, without completely breaking cultural ties with France.

Bibliography

- S. Thénault, Algeria:from “events” to war. Misconceptions about the Algerian War of Independence, Le Cavalier Bleu, coll. Misconceptions, 2012.

- B. Stora, History of the Algerian War (1954-1962), La Découverte, 2004.

- G. Pervillé, Atlas of the Algerian War, Otherwise, 2003.