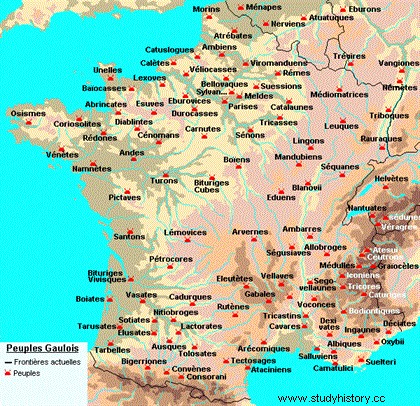

At the time of Celtic Gaul, the Arverni were a prosperous and influential people occupying the current region of Auvergne. They are mainly known by the general public through the figure of Vercingetorix and the famous Asterix comic strip in which the eponymous hero goes in search of the shield of the great "resistant" chief. However, the Arverni are much more than these images of Epinal:they were one of the most powerful peoples of Gaul who had an important role long before the war led by Caesar.

At the time of Celtic Gaul, the Arverni were a prosperous and influential people occupying the current region of Auvergne. They are mainly known by the general public through the figure of Vercingetorix and the famous Asterix comic strip in which the eponymous hero goes in search of the shield of the great "resistant" chief. However, the Arverni are much more than these images of Epinal:they were one of the most powerful peoples of Gaul who had an important role long before the war led by Caesar.

The appearance of the Arverni in the sources

However, is it possible to write the history of a people who have left no writings and whose only elements are found scattered in the stories of ethnographers, foreign historians or scientists such as Posidonius of Apamea, Appian or victors seeking to legitimize their conquests? If the task is not easy, it is not impossible. The results of recent archaeological excavations shed new light on the history of this people, representative of the changes that took place in central Gaul.

The origins of the Arverni people are unknown. Livy reports that they would have been part of the Bellovesos expedition (Roman history , V, 34) around 600 BC or the following century. The latter was the nephew of the biturige king Ambigatos and had the mission of seeking new territories to satisfy their populations and those of their allies. The historicity of this event is doubtful:according to the historian Wenceslas Kruta, it would be a founding myth of the insubre city Mediolanum (Milan).

The Arverni seem to appear for the first time with certainty in Roman accounts during the Second Punic War. The latter provided troops in 207 to Hasdrubal in Spain, who came to the aid of his brother Hannibal (Livy, Roman History , XXVII, 39). The information on this people from this date is more numerous but subject to debate. They are a preeminent people and fight for hegemony within Gaul with the Aedui. Hegemony must be understood in the Greek sense of the term:political and military superiority over neighboring peoples. The hold of the Arvernian hegemony seems to have reached central and southern Gaul at its peak.

L  e first king of this people whose name we have preserved is Luern (mid-2nd century BC). He was known for his wealth and prodigality. A fragment of Posidonius from Apamea (around 135 BC - around 51 BC) preserved thanks to the Deipnosophists of Athenaeum (late 2nd-early 3rd century AD). ) is particularly evocative in this respect; “Luern, to win the favor of the multitude, had himself carried in a chariot through the countryside, and threw gold and silver to the myriads of Celts who followed him. He had a space of twelve square stadia enclosed, on which he had vats filled with drinks of great price, and such quantities of food prepared that, for several days, he was allowed to those who wanted to enter the pregnant to taste the dishes that we had prepared and that were available without interruption. »

e first king of this people whose name we have preserved is Luern (mid-2nd century BC). He was known for his wealth and prodigality. A fragment of Posidonius from Apamea (around 135 BC - around 51 BC) preserved thanks to the Deipnosophists of Athenaeum (late 2nd-early 3rd century AD). ) is particularly evocative in this respect; “Luern, to win the favor of the multitude, had himself carried in a chariot through the countryside, and threw gold and silver to the myriads of Celts who followed him. He had a space of twelve square stadia enclosed, on which he had vats filled with drinks of great price, and such quantities of food prepared that, for several days, he was allowed to those who wanted to enter the pregnant to taste the dishes that we had prepared and that were available without interruption. »

Before continuing, it is necessary to clarify what is meant by royalty. The term king refers to the Gallic word rix which resembles rex in Latin. However, it does not fully have the meaning given to it today:many Gallic names have a -rix suffix (Orgetorix, Ambrorix, Cingetorix, Dumnorix and the famous Vercingetorix).

For Jean-Louis Brunaux, the Gallic kings are not the "holders of supreme authority" (Voyage en Gaule , p. 150) but magistrates responsible for a given period of defending the city. For this researcher, warrior societies can hardly accept the value of a man outside a battlefield. Stephan Fichtl or Frédéric Trément and his collaborators (2002) think that there were two consecutive systems, “classical” royalty and then oligarchic regimes. Among the Arverni, this passage would have taken place shortly after the end of the reign of Luern's son, Bituit.

Roman actions in southern Gaul and Cimbri incursions in the late 2nd century destabilize Arverni hegemony. Rome intervened following requests for help from its Massaliote allies against the Salyans and the Aedui against the Arverni who had just "ravaged" their territory. It crosses the Alps and, from 125, controls new territories at the expense of the Salyens and their Voconces and Ligurian allies. The Celtic-Ligurian alliance is defeated, the capital of the Salyes, Entremont, is taken in 123 and the population of the city is reduced to slavery. The Salyan chiefs (dunastai) and their king Teutomatos fled and took refuge with the Allobroges.

According to Livy, this choice is not neutral because the Salyans had participated, like the Allobroges, in the attack against the Aedui. Thus an alliance and privileged relations between these three peoples take shape. The Allobroges who welcomed the Salyan chiefs do not wish to hand over the fugitives. The Arvernian king Bituit seems to have had a more conciliatory position at this time and tried according to Appian to negotiate with Rome:

The ancient Roman sources on the episodes that follow are so diverse that it is very difficult to trace a complete and coherent account. With the failure of the embassy, the battle becomes the only way to resolve the conflict. After a defeat of the Allobroges near the city of Vindalium against Cneius Domitius Ahenobarbus, the army of Bituit was defeated in 121 BC. J.-C. by that of the consul Quintus Fabius Maximus undoubtedly joined by that of Cneius Domitius at the confluence of the Rhône and the Isère. A trophy commemorating the victory is raised on the spot. The Roman general then receives a triumph and the agnomen Allobrogicus.

The Arverni remain independent unlike their Allobrogian and Salyan allies. Perhaps Rome imposed on the Arvernes in the peace treaty to change the political regime that we identify in the following century? Be that as it may, the Arvernian king is brought to Rome and is present during the triumph:"Nothing in the triumph was so remarkable as King Bituitus, covered with arms of various colors, and mounted on a chariot silver, as he had fought. (Florus, Compendium of Roman History , I-37). Fallen, the son of Luern ends his life in exile in Albe with his son Congentiat. The latter may have returned to his family after his stay. In any case, the Arvernian hegemony in southern Gaul is obsolete and the Arvernians must take into account the arrival on their northern borders of this threatening power.

The Arvernian Territory

The territory of Arvernes includes the current departments of Puy-de-Dôme, as well as a portion of Allier, Haute-Loire and Cantal. Many axes of communication cross the territory including the Allier allowing access to the outlets of the Loire. Caesar indicates that the Arvernian territory was divided into pagi (Gallic War , VII, 64, 6). This division should not hide a strong centrality from the 3rd century around the plain of Clermont-Ferrand. This centrality is not observed among the Aedui (centrifugal system) and among the Bituriges (uniform system with oppida equally and regularly distributed over the territory).

The Gandaillat / La Grande Borne complex extending over 150 hectares a few kilometers east of Clermont seems to have been a central place in the Arverne city between the 3rd and 2nd c. Before our era. It is not impossible that it is the capital Nemossos known thanks to the Roman writings. The site was abandoned from the end of the 2nd century and replaced by three other oppida Corent, Gergovie and Gondole with an area of approximately 70 hectares each. This assessment must however be nuanced:the oppida of Bègues, Saint-Just-de-Baffie or Cusset located on the outskirts could be secondary centers with a certain importance.

The Arvernian territory has experienced continuous population and economic growth since the 3rd century. The plain of Limagne is the heart of it and is densely populated (between 200,000 and 300,000 inhabitants between the end of the 2nd century and the beginning of the 1st century). Archaeologists have clearly shown that this space was the breadbasket of the Arvernes. The agriculture practiced there can be described as intensive and requires significant irrigation and drainage for its sustainability. This development is only possible at the cost of constant efforts due to its consequences (acceleration of erosion, accumulation of black earth, deforestation, climatic fluctuations, etc.). Many mines are attested throughout the territory (gold in particular).

The Arvernian territory has experienced continuous population and economic growth since the 3rd century. The plain of Limagne is the heart of it and is densely populated (between 200,000 and 300,000 inhabitants between the end of the 2nd century and the beginning of the 1st century). Archaeologists have clearly shown that this space was the breadbasket of the Arvernes. The agriculture practiced there can be described as intensive and requires significant irrigation and drainage for its sustainability. This development is only possible at the cost of constant efforts due to its consequences (acceleration of erosion, accumulation of black earth, deforestation, climatic fluctuations, etc.). Many mines are attested throughout the territory (gold in particular).

Craftsmanship is not to be outdone:archaeologists have spotted the appearance of a "standard tableware service" in the 2nd century and have also found many painted ceramics dating from the same period. These disappear with the standardization of productions in the 1st century. The intensification of exchanges results in the creation of a currency which is used daily from the second half of the 2nd century and whose distribution area exceeds the limits of the city (a large part of the coins originating from Gaul Chevelue found in the south of France are Arvernes). This reflects their economic importance in the region. This development is accompanied by a growth in imports of wine amphoras which is reflected in the growing attraction that Rome exerts on the city.

Arverni on the eve of Caesar's conquests

The influence of the Arverni seems to have been reduced to the Cadurci, the Gabales, the Vellavi and the Eleutetes in the 1st century BC. However, their importance remains considerable and is made possible by the economic development mentioned above. In the middle of the 1st century BC, the city was ruled by an aristocracy which adopted an oligarchic system similar to that of Rome. The members of this aristocracy debate in an assembly (perhaps discovered at Corent) and compete for power. The personalization of currencies and the profusion of banquets reflect the extent of the political struggles. Despite its dissensions, political control over the territory of the city is reinforced and there is a scarcity of “foreign” pieces within it. This elite owns vast agricultural estates as shown by the discovery of tombs at Chaniat-Malintrat which contained pieces of armament, ornaments, amphoras, metal dishes, etc. Excavations at Corent have also brought to light the wealth and refinement of this aristocracy. The mansions are vast and influenced by the Roman model.

The Arverni also adopted before the conquest to some extent certain elements of Roman architecture as shown by the excavations at the Corent site. The wooden sanctuary from the beginning of the 1st century BC is reminiscent of those around the Mediterranean. Mathieu Poux, Matthieu Demierre, Romain Guichon and Audrey Pranyes in an article quoted in the bibliography establish a parallel between the public square of Corent and the Roman forum. This imitation is evoked by Caesar among the Carnutes when he describes their city Avaricum (Bell. Gall, VII, 28). This organization is also found in Alésia. The authors remind in their article that these forums should not be compared to those better preserved and better known from the imperial period.

The Arverni also adopted before the conquest to some extent certain elements of Roman architecture as shown by the excavations at the Corent site. The wooden sanctuary from the beginning of the 1st century BC is reminiscent of those around the Mediterranean. Mathieu Poux, Matthieu Demierre, Romain Guichon and Audrey Pranyes in an article quoted in the bibliography establish a parallel between the public square of Corent and the Roman forum. This imitation is evoked by Caesar among the Carnutes when he describes their city Avaricum (Bell. Gall, VII, 28). This organization is also found in Alésia. The authors remind in their article that these forums should not be compared to those better preserved and better known from the imperial period.

Dwellings in the city partly imitate Italic domestic constructions (surfaces covered with a crushed pozzolan screed similar to Roman pozzolan mortar floors; the plan of the houses with a interior courtyard, etc.). Arvernian modernization clearly had its sights set on the Roman model. All this necessarily generated significant political tensions, in particular on the attitude to adopt towards Rome and the new practices throughout the first half of the 1st century AD. These will come to light with the Gallic Wars.

The Arverni during the Gallic Wars

At the start of the war, the Arverni are withdrawn from events and respect the treaty (foedus ) passed with the Romans. But Vercingetorix breaks this neutrality by putting himself at the head of the revolt. We will not discuss the history and role of Vercingetorix in this war in detail which would require a complete article. We will only recall that he is the son of Celtillos who would have sought to impose royalty on Gaul a few years or even decades earlier. This last point is disputed by certain authors like Laurent Lamoine who sees in him only a magnate with a considerable influence on the city but without real political power.

At the head of the anti-Roman "party", Celtillos is executed by the city. His son is to some extent his political heir. We know Vercingetorix was part of Caesar's military entourage, perhaps as a hostage delivered by the cities. This trip allowed him to acquire useful military and political know-how against the Romans. This one returns in the city but its projects of conquest of the power and resistance come up against the interests of other aristocrats. Gobannitio, his uncle and probable member of the pro-Roman “party”, bars his way and exiles him from Gergovia. Taking advantage of the massacre of Roman traders at Cenabum by the Carnutes (signal of the beginning of the revolt in Celtic) between the end of the year 53 and the beginning of the year 52, the young man returned to the city with an army and took the power. Local aristocrats join his cause like Vercassivellaunos, his cousin or Critognatos "of high birth and who enjoyed high consideration" according to Caesar. Vercingetorix sends embassies to other peoples, rallies supporters and takes the lead in the revolt. After the victory of Gergovie, the epic of the rebels ends with the defeat of Alésia a few months later in 52.

The insurrectionary episode ended, the Arverne city once again sided with Rome. Epasnactos had significant political power in the city from at least the 1950s, as evidenced by the "EPAD" coins. During the Gallic Wars, it issued “EPAD” coins with a horseman while after the conquest, it issued coins with a soldier on foot and a Roman ensign. The weight of the second type of coins aligns with the Roman quinary. The acceptance of Roman supremacy is reflected in the Arverne coinage. It is very likely that he was always a member of the pro-Roman "party" and that he therefore constituted a weighty ally for Rome in the new political order it sought to establish.

The insurrectionary episode ended, the Arverne city once again sided with Rome. Epasnactos had significant political power in the city from at least the 1950s, as evidenced by the "EPAD" coins. During the Gallic Wars, it issued “EPAD” coins with a horseman while after the conquest, it issued coins with a soldier on foot and a Roman ensign. The weight of the second type of coins aligns with the Roman quinary. The acceptance of Roman supremacy is reflected in the Arverne coinage. It is very likely that he was always a member of the pro-Roman "party" and that he therefore constituted a weighty ally for Rome in the new political order it sought to establish.

Caesar spares Arverni and grants them the privileged status of a free city. The latter will return it well because they will never again rise against the central power and will not take part in the later civil wars (unlike other cities). The transfer of political power to Augustonemetum at the end of the 1st century BC under Augustus sealed and definitively marked the entry of this people into the era of Roman domination. Finally, the construction of the Temple of Mercury Arverne in the 1st century on the summit of Puy-de-Dôme completed the passage of the city into the Roman world.

The Arvernes reveal the evolutions that Iron Age societies went through in Central Gaul. This important people with a broad influence, initially opposed to Rome, then seeks to obtain the good graces of the neighboring power even if internal opposition sometimes manifests itself in a violent way as illustrated by the Vercingetorix episode. Influenced very early on by Rome, he is emblematic of the new historiographical trend which insists on ancient contacts with Rome. These contacts are accompanied by economic exchanges and by an increasingly strong attraction for the Roman model.

Conquest is no more than the realization of this increasingly significant domination. If the history of this people is more difficult to retrace in Roman times due to the lack of sources, we can nevertheless say that the city had a certain economic importance with the continuation of intensive agriculture and the production of sigillated ceramics. in Lezoux and it certainly also had a political importance of which we only perceive a few fragments today.

Some Arverni statues (whether that of Mercury for the temple by Zenodorus from the 1st century or the foot of a recently discovered monumental statue dating from the beginning of the 2nd century certainly representing a imperial character) show the high degree of refinement of the Arverni. Sidonius Apollinaris in the 5th century allows us to find more numerous sources thanks to his writings:defender of Roman culture and very close to imperial power, he chose the ecclesiastical path and became a leading political figure among his people. A journey also emblematic of its time.

Indicative bibliography

- BRUNAUX Jean-Louis, Journey to Gaul, Seuil, 2011.

- BRUNAUX Jean-Louis, The Gauls, Beautiful Letters, 2005.

- BRUNAUX Jean-Louis, Alesia, Gallimard, 2012.

- KRUTA Wenceslas, The Celts:History and Dictionary. From origins to Romanization and Christianity, Robert Laffont, 2000.