The Brazilian economy is considered, in 2018, the ninth world economy and the first in Latin America, according to IMF data. Brazil's GDP is estimated at 2.14 trillion dollars.

The country reached the position of seventh world economy in 1995 and has remained among the top ten economies since then.

It is important to remember that economic indicators do not necessarily reflect good social indicators.

Economy of Brazil Current

The current Brazilian economy is diversified and covers three sectors:primary, secondary and tertiary. The country has long abandoned monoculture or targeting only one type of industry.

Today, the Brazilian economy is based on agricultural production, which makes Brazil one of the main exporters of soy, chicken and orange juice in the world. It is still the leader in the production of sugar and sugarcane derivatives, cellulose and tropical fruits.

Likewise, it has an important meat industry, with the creation and slaughter of animals, occupying the position of third producer of bovine meat in the world.

Check out EcoAgro's 2012 data on Brazilian agribusiness:

In terms of the manufacturing industry, Brazil stands out in the production of parts to supply the automotive and aeronautical sectors.

Likewise, it is one of the main oil producers in the world, dominating the exploration of oil in deep waters. Even so, it stands out in the production of iron ore.

See also:What is Agribusiness?History of the Brazilian Economy

The first market to be explored in the territory of America by Portugal was pau-brasil (Caesalpinia echinata ).

The tree was found in abundance along the coast and through it, Brazil got its name. This species is medium in size, reaching 10 meters in height and has many spines.

With a yellow flower, pau-brasil has a reddish trunk that after processing was used as a dye for fabrics.

The economic history of Brazil can be studied through economic cycles. These were elaborated by the historian and economist Caio Prado Jr. (1907-1990) as an attempt to explain the paths of the Brazilian economy.

See also:Extractivism in BrazilPau-Brasil Cycle

The pau-brasil was found in most of the coast of the Brazilian coast, in a range that went from Rio Grande do Norte to Rio de Janeiro. The extraction was done by indigenous labor and obtained through barter.

In addition to its use for extracting dye, pau-brasil was useful in the production of wooden utensils, in the making of musical instruments and used in construction.

Three years after the discovery, Brazil already had a timber extraction complex.

See also:Pau-Brasil cycleSugar Cane Cycle

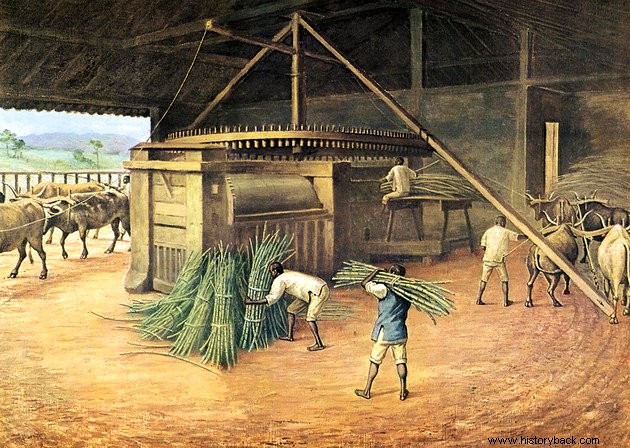

After the pau-brasil supply - which became practically extinct - the Portuguese began to explore sugarcane in their colony of America. This cycle lasted more than a century and had a significant impact on the colonial economy.

The colonists installed sugar mills on the coast, which were made using slave labor. The mills were located throughout the northeast, but mainly in Pernambuco.

As there were difficulties in mastering the logistics of sugarcane exploration, support for the sugar industry was obtained from the Dutch, who became responsible for the distribution and commercialization of sugar to the European market.

Among the consequences of this cultivation is the deforestation of the Brazilian coast and the arrival of more Portuguese to participate in the immense profits generated in the Portuguese colony. There is also the importation of Africans as slaves to work on the plantations.

As a monoculture, the exploitation of sugarcane was based on the structure of large estates - large land holdings - and on slave labor. This was supported by the slave trade, dominated by England and Portugal.

The colonists also engaged in other economic activities such as searching for precious metals. This led expeditions, known as entrances and flags, to the interior of the colony to find gold, silver, diamonds and emeralds.

See also:Sugarcane CycleGold Cycle

The search for precious stones and metals peaked in the 18th century, between 1709 and 1720, in the captaincy of São Paulo. At that time, this region included what is now Paraná, Minas Gerais, Goiás and Mato Grosso.

The exploitation of precious metals and stones was boosted by the decline of the sugarcane activity, in frank decadence after the Dutch started planting sugarcane in their colonies in Central America.

With the discovery of mines and nuggets in the rivers of Minas Gerais, the so-called gold cycle begins. The wealth that came from the interior of the country influenced the transfer of the capital, previously in Salvador, to Rio de Janeiro, in order to control the exit of the precious metal.

The Portuguese Crown surcharged the colony's products and collected taxes, called fifth, spills and capitation were paid at the Foundry Houses.

The fifth corresponded to 20% of all production. The spill, on the other hand, represented 1,500 kilos of gold that had to be paid each year under penalty of compulsory pledge of the miners' assets. In turn, capitation was the rate corresponding to each slave who worked in the mines.

The settlers' dissatisfaction with the collection of taxes, considered abusive, culminated in the movement called Inconfidência Mineira, in 1789.

The search for gold influenced the process of settlement and occupation of the colony, expanding the limits of the Treaty of Tordesillas.

This cycle lasted until 1785, coinciding with the beginning of the Industrial Revolution in England.

See also:Gold CycleCoffee Cycle

The coffee cycle was responsible for boosting the Brazilian economy in the early 19th century. This period was marked by the intense development of the country, with the expansion of railways, industrialization and the attraction of European immigrants.

The grain, of Ethiopian origin, was cultivated by the Dutch in French Guiana and arrived in Brazil in 1720, being cultivated in Pará and later in Maranhão, Vale do Paraíba (RJ) and São Paulo. Coffee plantations also spread across Minas Gerais and Espírito Santo.

Exports began in 1816 and the product led the export list between 1830 and 1840.

Most of the production was in the state of São Paulo. The high amount of grain favored the modernization of transport modes, notably rail and ports.

The flow was made through the ports of Rio de Janeiro and Santos, which received funds for adaptation and improvements.

At this historic moment, slave labor had been abolished and farmers did not want to take advantage of freed workers, most of the time because of prejudice.

So there was a need to find more hands for farming, a condition that attracted European immigrants, especially the Italians.

After almost a hundred years of prosperity, Brazil began to face a crisis of overproduction:there was more coffee to sell than buyers.

In the same way, the coffee cycle came to an end as a result of the New York Stock Exchange crash in 1929. Without buyers, the coffee industry declined in importance in the Brazilian economic scenario from the 1950s onwards.

The fall in coffee production also represented a milestone for the country in terms of diversifying its economic base.

The infrastructure, previously used for the transport of grains, was the support for the industry, which starts to manufacture products of simplified elaboration, such as fabrics, food, soap and candles.

See also:Coffee CycleBrazilian Economy and Industrialization

The government of Getúlio Vargas (1882-1954) began to encourage the installation of heavy industry in Brazil, such as steel and petrochemicals.

This led to a rural exodus in several parts of the country, especially in the northeast, where the population was fleeing rural decay.

Measures for the benefit of industry were favored by the outbreak of the Second World War. At the end of the conflict, in 1945, Europe was devastated and the Brazilian government invested in a modern industrial park to supply itself.

See also:Industrialization in BrazilKubitschek goals

Industry becomes the center of attention in the government of Juscelino Kubitschek (1902-1976), which implements the Plan of Goals, called 50 years in 5. JK predicted that Brazil would grow in 5 years what had not grown in 50 .

The Goals Plan indicated the five sectors of the Brazilian economy where resources should be channeled:energy, transport, food, basic industry and education.

It also included the construction of Brasília and, later, the transfer of the country's capital.

Economic Miracle

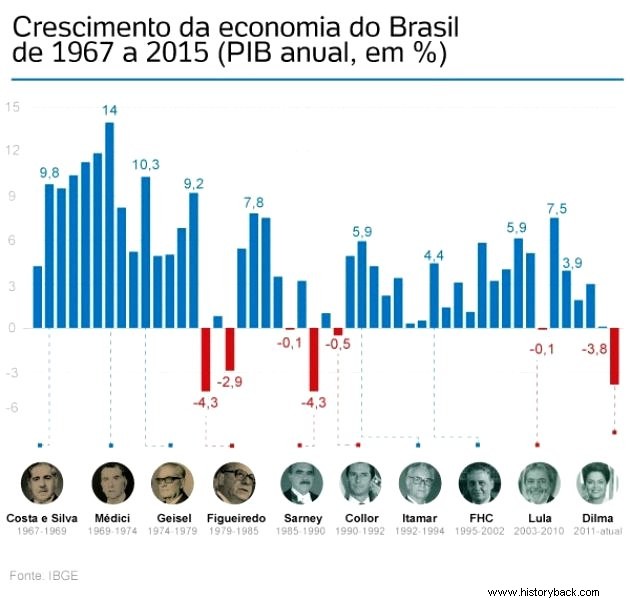

During the military dictatorship, governments open the country to foreign investments that boost infrastructure. Between 1969 and 1973, Brazil lived the cycle called the Economic Miracle, when the GDP grew by 12%.

It is in this phase that major works are built, such as the Rio-Niterói bridge, the Itaipu hydroelectric plant and the Transamazon Highway.

However, these works were expensive and also cause floating interest borrowing. Thus, there was an inflation of 18% per year and the country's growing debt, despite the generation of thousands of jobs.

The Economic Miracle did not allow full development, as the economic model favored big capital and income concentration increased.

On the part of the primary sector, the production of soy was already the main commodity since the 1970s. export.

Unlike crops such as coffee, which required abundant labor, soybean cultivation is marked by mechanization, which generates unemployment in the countryside.

Still in the 1970s, Brazil was heavily impacted by the crisis in the international oil market, which caused fuel prices to rise.

In this way, the government encourages the creation of alcohol as an alternative fuel to the national vehicle fleet.

The Lost Decade - 1980

The period is marked by the insufficiency of Union resources for the payment of the external debt.

At the same time, the country needed to adapt to the new paradigms of the world economy, which provided for technological innovations and the growing influence of the financial sector.

During this period, 8% of the national GDP is directed to the payment of the external debt, the per capita income is stagnant and inflation increases dramatically.

Since then, there has been a succession of economic plans to try to contain inflation and resume growth, without success. That's why economists called the 1980s the "lost decade".

Observe the evolution of Brazil's GDP from 1965 to 2015:

Foreign Debt and Brazilian Economy

At the end of the military government, the Brazilian economy was showing signs of wear and tear on account of the high interest charged to pay the foreign debt. Brazil thus became the largest debtor among developing countries.

The GDP plummeted from a growth of 10.2% in 1980 to a negative 4.3% in 1981, as attested by the IBGE (Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics).

The solution was to make economic plans aimed at stabilizing the currency and controlling inflation.

See also:Economic Crisis in BrazilEconomic Plans

With the economy in strong recession, foreign debt and loss of purchasing power, Brazil launched economic plans to try to recover the economy.

Economic plans tried to devalue the currency in order to contain inflation. Between 1984 and 1994, the country had several different currencies:

| Currency | Period |

|---|---|

| Cruise | August 1984 and February 1986 |

| Cross | February 1986 and January 1989 |

| New Crusade | January 1989 and March 1990 |

| Cruise | March 1990 to 1993 |

| Royal Cruise | August 1993 to June 1994 |

| Real | From 1994 to the present |

Cross Plan

The first measure of economic intervention took place when President José Sarney took office, in January 1986. Finance Minister Dilson Funaro (1933-1989) launched the Cruzado Plan, which provided for the control of inflation through price freezes.

There were still the Bresser plans in 1987 and the summer in 1989. Both were unable to stop the inflationary process and the Brazilian economy remained stagnant.

Collor Plan

With the election of Fernando Collor de Mello, in 1989, Brazil would adopt neoliberal ideas, where opening the national economy was the priority.

The privatization of public companies, a reduction in the civil service and an increase in the participation of private entrepreneurs in various economic sectors were also foreseen.

However, due to the corruption scandals, the president found himself involved in an impeachment process that cost him his presidential office.

See also:Collor PlanReal Plan

Brazil had 13 economic stabilization plans. The last one, the Real Plan, provided for the exchange of the currency to the Real from July 1, 1994, during the government of Itamar Franco (1930-2011).

The implementation of the plan was under the command of the Minister of Finance, Fernando Henrique Cardoso. The Real Plan provided for the effective control of inflation, the balance of public accounts and the establishment of a new monetary standard, pegging the value of the real to the dollar.

Since then, Brazil has entered an era of monetary stability that would continue into the 21st century.

See also:Neoliberalism in BrazilRead more about some related topics :

- Agriculture in Brazil

- Brazilian Business Cycles

- Lula Government

- Cotton Cycle

- Economy of the Southern Region

- Economy of the Southeast Region

- Economy of the Northeast Region

- Brazil