Economic Miracle or "Brazilian economic miracle" corresponds to the economic growth that took place in Brazil between 1968 and 1973.

This period was characterized by the acceleration of GDP (Gross Domestic Product) growth, industrialization and low inflation.

However, behind the prosperity, there was increased concentration of income, corruption and exploitation of the workforce.

It was during the government of President Emílio Médici (1969-1974) that the economic miracle reached its peak.

Origin of the Economic Miracle

The beginning of the economic miracle is in the creation of the Government Economic Action Program (Paeg) in the administration of President Castelo Branco (1964-1967).

The Paeg provided for an incentive to exports, opening up to foreign capital, as well as reform in the fiscal, tax and financial areas.

During the economic miracle, GDP reached 11.1% annual growth.

The Central Bank was created to centralize economic decisions. Likewise, in order to favor credit and solve the housing deficit, the government instituted the SFH (Housing Financial System), formed by BNH (National Housing Bank) and CEF (Caixa Econômica Federal).

The main source of funds for the housing system would come from the FGTS (Fundo de Garantia do Tempo de Serviço). This tax, created in 1966, was deducted from workers and was used to stimulate civil construction.

The creation of banks was also favored to stimulate the capital market and the opening of credit to the consumer, improving, among others, the performance of the automobile industry.

Furthermore, no more than 274 state-owned companies, such as Telebrás, Embratel and Infraero were opened in this period.

At the time, the Minister of Finance, Delfim Neto, justified these measures as fundamental to boosting the country's growth. Delfim Neto used the metaphor that “the cake needed to grow and then be shared”.

See also:Military Dictatorship in Brazil (1964-1985)Works during the Economic Miracle

In addition to the incentive measures, the economic miracle was achieved through large-scale works such as roads and hydroelectric plants.

Among these we can mention the Trans-Amazonian highway (which links Pará to Paraíba), the Perimetral Norte (Amazonas, Pará, Amapá and Roraima) and the Rio-Niterói bridge (connecting the cities of Rio de Janeiro and Niterói).

We can also mention the Itaipu Power Plant, the Angra nuclear power plants and the Manaus Free Trade Zone.

The resources for these works were obtained through international loans, which increased the external debt. International financing was also used to leverage mining projects, such as those at the Carajás and Trombetas plants, both in Pará.

The consumer goods industries (machinery and equipment), pharmaceuticals and agriculture also received international resources. The agricultural sector turned to monoculture, targeting the international market.

These infrastructure works were necessary in a growing country with the dimensions of Brazil. However, they were made in a non-transparent way and consumed much more resources than initially anticipated.

To attract business, the federal government flattened workers' wages. As the unions were under intervention, negotiations almost always favored the entrepreneur. At this time, with poor inspection, work accidents multiplied.

See also:Emílio Medici:biography and governmentEnd of the Economic Miracle

In the external scenario, the situation changed after 1973, when the First Oil Shock took place. This year, producing countries stopped selling oil to countries that were allied with Israel. Thus, the price of a barrel quadrupled in just one year, making industrial production more expensive.

To face this rise in prices, the United States raised interest rates on the international market in the 1970s and reduced remittances to developing countries.

Brazil stopped receiving loans and started paying exorbitant interest on its foreign debt. As a result, there was a wage squeeze, currency devaluation and a reduction in the purchasing power of the population.

The minimum wage was below US$ 100 resulting in an increase in poverty and misery.

Economic policy favored exports and imposed heavy burdens on imports. The strategy resulted in the scrapping of national industries.

For these reasons, the industrial sector could not import machines and modernize factories that, being obsolete, lost competitiveness.

Economic Miracle Summary

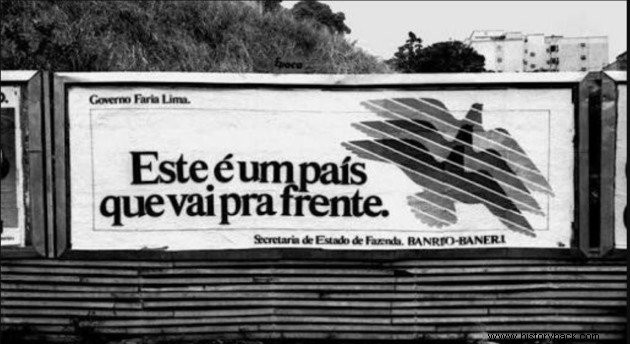

To this day the legacy of the "economic miracle" is much discussed among historians and economists. This is due, in part, to the propaganda that the government of General Emílio Médici (1970-1974) made of Brazilian economic growth.

The victory of the men's soccer team, for example, helped to convey this positive image in Brazil.

Despite having been carried out in an authoritarian environment that harmed workers, the “economic miracle” left marks that survive to this day. Let's see:

Positive Points

- Construction of important works, such as the Rio-Niterói bridge and the Itaipu power plant

- Acceleration of industrialization

- Incentive to the construction industry with the creation of the Housing Financial System

Negative Points

- Increasing poverty

- Rising Inflation

- Reducing the purchasing power of the working poor

- Minimum investment in health, education and social security

- Devaluation of the Brazilian currency against the dollar

- Increase in external debt

- Corruption and favoring government-related contractors

- Reliance on borrowing from abroad, mainly from the United States

Consequences of the Economic Miracle

The economic policy of the dictatorial regime was centralized, favoring the increase of the public machine and favoring the richest strata with tax exemption.

Thus, there was a high deficit in the minimum wage and a reduction in the income of the poorest strata of the population. On the other hand, the richest accumulated earnings.

Services in areas such as health, education and social security were harmed, as they did not keep up with population growth and did not receive investments. In this way, they lost quality and efficiency.

See also:Redemocratization of BrazilLost Decade

The 1980s are considered a lost decade for Brazil and Latin America. The denomination is used to explain the effects of the end of the period of the economic miracle.

During this decade, the government ceased to be the main investor and the business community was unable to meet the expenses. There was also an increase in external debt, poverty and a reduction in exports. Brazil became more dependent on foreign capital and the industry stagnated.

There was also an intense reduction in wages, with the consequent fall in the purchasing power of the population. GDP fell and unemployment increased, as well as misery.

See also:Economy of Brazil Want to know more about the period of the Military Dictatorship? Read these texts :

- Industrialization in Brazil

- What is dictatorship?

- Direct Now

- Institutional Act No. 5 - AI-5

- Geography Enem:subjects that fall the most