The European maritime expansion it was the period between the 15th and 18th centuries when some European peoples set out to explore the ocean that surrounded them.

These trips started the process of the Commercial Revolution, meeting different cultures and exploring the new world, enabling the interconnection of continents.

Overseas expansion

The first great navigations allowed the overcoming of the commercial barriers of the Middle Ages, the development of the mercantile economy and the strengthening of the bourgeoisie.

The European's need to take to the sea resulted from a series of social, political, economic and technological factors.

Europe was emerging from the crisis of the 14th century and national monarchies were led to new challenges that would result in expansion into other territories.

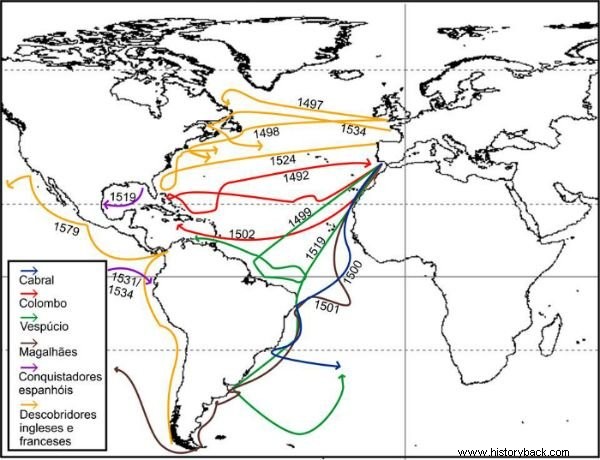

See on the map below the routes taken towards the West by navigators and the year of travel:

Europe was going through a moment of crisis, as it bought more than it sold. On the European continent, the supply was wood, stones, copper, iron, tin, lead, wool, linen, fruit, wheat, fish, meat.

The countries of the East, in turn, had sugar, gold, camphor, sandalwood, porcelain, precious stones, cloves, cinnamon, pepper, nutmeg, ginger, ointments, aromatic oils, medicinal drugs and perfumes.

It was up to the Arabs to transport the products to Europe in caravans carried out by land routes. The destination was the Italian cities of Genoa and Venice that served as intermediaries for the sale of goods to the rest of the continent.

Another available route was through the Mediterranean Sea monopolized by Venice. Therefore, it was necessary to find an alternative, faster, safer and, above all, economical way.

Parallel to the need for a new passage, it was necessary to solve the metal crisis in Europe, where the mines were already showing signs of exhaustion.

A social and political reorganization also led to the search for more routes. It was the alliances between kings and the bourgeoisie that formed the national monarchies.

Bourgeois capital would finance the expensive and necessary infrastructure for the sea feat. After all, ships, weapons, navigators and supplies were needed.

The bourgeois paid and received in return a share in the profits of travel. This was a way of strengthening national states and submitting society to a centralized government.

In the field of technology, it was necessary to improve cartography, astronomy and nautical engineering.

The Portuguese took the lead in this process by calling the Escola de Sagres. Although it was not an institution as we know it today, it served to bring together navigators and scholars under the patronage of Infante Dom Henrique (1394-1460).

See also:Commercial RenaissancePortugal

Portuguese maritime expansion began through conquests on the coast of Africa and expanded to nearby archipelagos. Experienced fishermen, they used small boats, the barinel, to explore the surroundings.

Later, they would develop and build the caravels and ships in order to be able to go further and more safely

Nautical precision was favored by the compass and astrolabe, which came from China. The compass was already used by Muslims in the twelfth century and is intended to point north (or south). In turn, the astrolabe is used to calculate distances taking the position of celestial bodies as a measure.

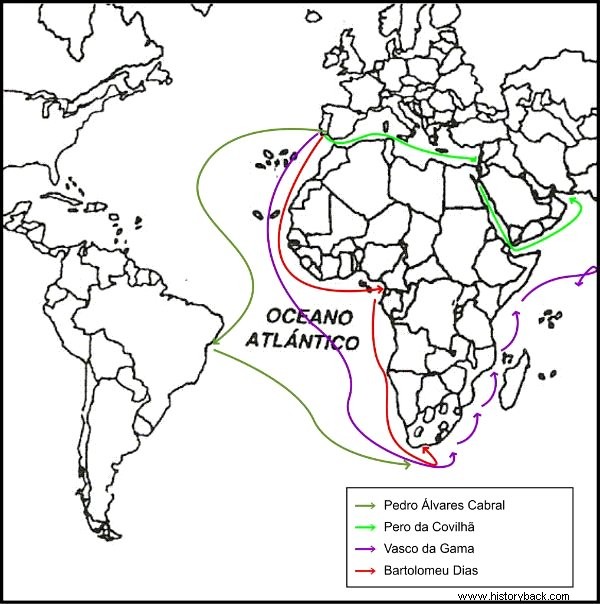

On the map below you can see the routes taken by the Portuguese:

With developed technology and the economic need to explore the ocean, the Portuguese also added the desire to take the Catholic faith to other peoples.

Political conditions were quite favourable. Portugal was the first nation to create a national state associated with mercantile interests through the Avis Revolution.

In peace, while other nations were at war, there was a central coordination to stimulate and organize maritime incursions. These would be essential to fill the shortage of labor, agricultural products and precious metals.

The first Portuguese success on the seas was the Conquest of Ceuta, in 1415. Under the pretext of religious conquest against the Muslims, the Portuguese dominated the port that was the destination of several Arab commercial expeditions.

Thus, Portugal established itself in Africa, but it was not possible to intercept the caravans loaded with slaves, gold, pepper, ivory, which stopped in Ceuta. The Arabs looked for other routes and the Portuguese were forced to look for new ways to obtain the goods they so aspired to.

In an attempt to reach India, Portuguese navigators circumvented Africa and settled on the coast of this continent. They created trading posts, forts, ports and points for negotiation with the natives.

These incursions were called the African tour and were intended to make a profit through trade. There was no interest in colonizing or organizing the production of any product in the exploited places.

In 1431, Portuguese navigators arrived in the Azores islands, and later occupied Madeira and Cape Verde. Cabo do Bojador was reached in 1434, in an expedition commanded by Gil Eanes. The African slave trade was already a reality in 1460, with the withdrawal of people from Senegal to Sierra Leone.

It was in 1488 that the Portuguese arrived at the Cape of Good Hope under the command of Bartolomeu Dias (1450-1500). This feat is one of the important marks of Portugal's maritime conquests, as in this way a route to the Indian Ocean was found as an alternative to the Mediterranean Sea.

Between 1498, the navigator Vasco da Gama (1469-1524) managed to reach Calicut, in the Indies, and there establish negotiations with the local chiefs.

Within this context, the fleet of Pedro Álvares Cabral (1467-1520), moved away from the coast of Africa in order to confirm if there were lands there. In this way, he arrives in the lands where Brazil would be, in 1500.

See also:Portuguese NavigationsSpain

Spain unified much of its territory with the fall of Granada in 1492, with the defeat of the last Arab kingdom. The first Spanish incursion into the sea resulted in the discovery of America by the Italian navigator Christopher Columbus (1452-1516).

Supported by Kings Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile, Columbus left in August 1492 with the caravels Nina and Pinta and with the ship Santa Maria heading west, arriving in America in October of the same year.

Two years later, Pope Alexander VI approved the Treaty of Tordesillas, which divided the discovered and undiscovered lands between the Spanish and Portuguese.

See also:Discovery of AmericaFrance

Through a criticism of the Treaty of Tordesillas made by King Francisco I, the French launched themselves in search of overseas territories. France emerged from the Hundred Years' War (1337-1453), from the struggles of King Louis XI (1461-1483) against feudal lords.

From 1520, the French began to make expeditions, arriving in Rio de Janeiro and Maranhão, from where they were expelled. In North America, they arrived in the region now occupied by Canada and the state of Louisiana, in the United States.

In the Caribbean, they settled in Haiti and in South America, in Guyana.

England

The English, who were also involved in the Hundred Years' War, War of the Two Roses (1455-1485) and conflicts with feudal lords, also wanted to seek a new route to the Indies via North America.

Thus, they occupied what would now be the United States and Canada. Likewise, they occupied islands in the Caribbean such as Jamaica and the Bahamas. In South America, they settled in present-day Guyana.

The methods employed by the country were quite aggressive and included encouraging piracy against Spain, with the consent of Queen Elizabeth I (1558-1603).

The British dominated the slave trade to Spanish America and also occupied several islands in the Pacific, colonizing present-day Australia and New Zealand.

See also:Slave ShipsNetherlands

Holland embarked on the conquest of new territories in order to improve the thriving trade they dominated. They managed to occupy several territories in America, settling in present-day Suriname and islands in the Caribbean, such as Curaçao.

In North America, they even founded the city of New Amsterdam, but were expelled by the British who renamed it New York.

Likewise, they tried to snatch northeast Brazil during the Iberian Union, but were repelled by the Spanish and Portuguese. In the Pacific, they occupied the Indonesian archipelago and would remain there for three and a half centuries.

See also:Dutch Invasions