The I ndependence of Brazil was proclaimed on 7 September 1822 , by the then Prince Regent, Dom Pedro de Alcântara.

This occasion is also called the "Grito de Independência", as, according to tradition, Dom Pedro would have said the phrase "independence or death" loud and clear to the guard who accompanied him on the banks of the Ipiranga stream, in São Paulo.

However, there is no consensus among historians as to the veracity of this cry.

On the 1st of December of the same year, D. Pedro was crowned Emperor of Brazil, with the title of D. Pedro I, a position he held until 1831.

Causes of Brazil's Independence

The Independence of Brazil occurred from the triggering of a series of factors. Therefore, the correct term to use is process.

Among the main factors that generated the independence process. Starting with the dmisunderstanding between Portuguese and Brazilian deputies in the Lisbon Courts. With the elevation of Brazil from Colonia to the United Kingdom to Portugal and the Algarves, Brazilian deputies began to act also in the Portuguese Courts.

This generated several frictions with the Lusitanians, who did not welcome the political autonomy that the Brazilian territory was gaining.

The will of the Brazilian economic elite to end the Portuguese commercial monopoly, established since the beginning of colonization, was another factor. Commercial monopoly occurs when a single company or group of companies is authorized to market a certain type of product.

The Exclusivo Metropolitano (or Colonial Pact) forced Brazil to buy industrialized products only from a few Portuguese companies, which raised the final price of items sold in the Colony.

This practice was common among colonizing countries, as it benefited a small number of Portuguese traders, who would have authorization to buy and sell products in Brazil.

Both in Europe and on the American continent, enlightenment ideas about the freedom of peoples echoed in Brazil and influenced separatist movements against Portuguese absolutism, such as Inconfidência Mineira, Conjuração Baiana and Pernambuco Revolution of 1817.

On the American continent, the various independences of the countries of Spanish America (regions of the American continent colonized by Spaniards) were also very important in the diffusion of anti-absolutist and revolutionary ideals (although, after independence, Brazil continued to be monarchist and with characteristics that centralized power in its constitution).

Brazil's Independence Process

The process of independence in Brazil is also different from other colonies in America, because here, the Portuguese Royal Family was installed from 1808 to 1820, making the struggle different from other territories.

Let's see how it happened.

The arrival of the Royal Family to Brazil

At the beginning of the 19th century, part of Europe was dominated by the troops of the Emperor of the French, Napoleon Bonaparte. His main enemy was England.

In 1806, the Emperor decreed the Continental Blockade, which forced all European nations to close their ports to English trade. The country that disobeyed the blockade would have its territory invaded by the French army. With that, Napoleon intended to defeat England by economic means.

At that time, Portugal was ruled by Prince Regent D. João, who was pressured by Napoleon to close Portuguese ports to English trade, so as not to trade with them anymore.

While not wanting to disobey Napoleon, Portugal needed to maintain trade relations with England, which was its main supplier of manufactured products, as well as a major buyer of Portuguese and Brazilian goods.

To resolve the situation, the English ambassador in Lisbon convinced D. João to transfer with the Court to Brazil. In this way, the English guaranteed access to the Brazilian market and the Portuguese Royal Family avoided the deposition of the Bragança dynasty by Napoleonic forces.

Thus, on November 29, 1807, the Royal Family, nobles and officials left for Brazil escorted by four British ships. The next day, French troops invaded Lisbon.

Arrival in Brazil

On January 22, 1808, D. João arrived in Salvador, where he decreed the Opening of the Ports of Brazil to the Friendly Nations of Portugal, ending the Exclusive Metropolitano.

This ended the Portuguese trade monopoly in Brazil. Quickly, English products began to arrive and a large number of English firms settled in Brazil.

During his stay in the capital of Bahia, D. João also founded the School of Surgery of Bahia, the equivalent of the current faculties of medicine. After three months in Salvador, he headed for Rio de Janeiro, where he disembarked in March of the same year.

In 1810, D. João signed the Treaty of Commerce and Navigation. Among other acts, this established a 15% tax on the importation of English products, while Portugal would pay 16% and other nations 24%.

In 1815, after the final defeat of Napoleon Bonaparte, the European powers met at the Congress of Vienna. The objective was to restore in Europe the absolutist regime before the French Revolution.

To obtain recognition of the Bragança dynasty and the right to participate in the Congress, on December 16, 1815, D. João elevated Brazil to the United Kingdom of Portugal and Algarves.

The step change was necessary because the Congress of Vienna would only accept the participation of monarchs who were in its territory during the Napoleonic invasions and who were overthrown by the French. As the Royal Family was outside their kingdom (that is, in the Colony), the Braganças needed to elevate Brazil's position to justify their participation.

Thus, Brazil ceased to be a colony and started to have the same political status as Portugal. This meant participating in the politics of the Kingdom, sending deputies to the Lisbon courts. It was an important step towards the political emancipation of the territory.

Pernambucan Revolution (1817)

However, not everyone was satisfied with the government of Dom João VI in Brazil. Several Brazilian provinces felt abandoned and saw that the improvements only benefited the capital.

In this way, in Recife, in the current state of Pernambuco, a revolt took place, which intended to found another country called the Confederation of Ecuador. Dom João VI's response was immediate and the movement repressed.

The Porto Revolution (1820)

Since the arrival of the Royal Family to Brazil, Portugal was on the brink of chaos. In addition to the serious economic crisis and popular discontent, the political system was marked by the tyranny of the English commander, William Carr Beresford, who ruled the country.

All this led the Portuguese to join the revolutionary movement, which began in the city of Porto on August 24, 1820.

The Liberal Revolution of Porto had the following objectives:

- Overthrow the English administration;

- Recolonize Brazil;

- Promote the return of D. João VI to Portugal

- Writing a Constitution.

Faced with these events, on March 7, 1821, D. João VI announced his departure. However, he left his eldest son and heir to the throne, Dom Pedro, in Brazil, making him regent of Brazil.

On April 26, 1821, D. João VI leaves for Portugal, with Queen Dona Carlota Joaquina, Prince Dom Miguel and the couple's daughters.

From Fico to Independence Day

The new regent of Brazil, D. Pedro, was 23 years old. Several measures by the Lisbon courts sought to diminish the power of the Prince Regent and, in this way, put an end to the autonomy of Brazil.

The insistence of the Cortes that D. Pedro return to Portugal aroused attitudes of resistance in Brazil. On January 9, 1822, a petition with 8,000 signatures was delivered to the Prince Regent asking him not to leave Brazilian territory.

Yielding to pressure D. Pedro replied:

The Dia do Fico was another step towards the independence of Brazil.

However, in some Brazilian provinces, the partisans of the Portuguese were not in favor of the government of D. Pedro.

General Avilés, commander of Rio de Janeiro and faithful to the Cortes of Lisbon, tried to force the regent to embark, but was frustrated by the mobilization of the Brazilians, who were occupying Campo de Santana.

The events triggered a crisis in the government, and the Portuguese ministers resigned. The prince formed a new ministry, under the leadership of José Bonifácio, until then vice-president of the Governing Board of São Paulo.

In the month of May, the Brazilian government established that the determinations coming from Portugal could only be accepted after the approval of D. Pedro.

Meanwhile, in Bahia, the fight between Portuguese and Brazilian troops was unleashed. In turn, the Courts in Portugal took measures such as:

- Declared the Constituent Assembly held in Brazil to be illegitimate;

- The Prince Regent's rule has been declared illegal;

- D. Pedro should immediately return to Portugal.

Faced with the attitude of the metropolis, the movement for separation gained more supporters.

Proclamation of Independence

Dom Pedro decided to leave for the province of São Paulo to secure the support of local leaders. Princess Dona Leopoldina would be the regent during her husband's absence.

On September 7, 1822 , returning to Rio de Janeiro, D. Pedro was on the banks of the Ipiranga stream in São Paulo, when he received the last decrees from Lisbon, one of which transformed him into a simple governor, subject to the authorities of the Courts.

This attitude led him to decide that the ties between Brazil and Portugal were severed. Thus, he ordered all those present to remove the Portuguese insignia they wore from their uniforms and would have shouted "Independence or Death".

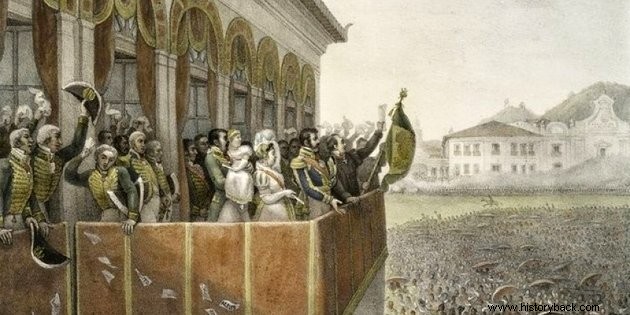

On October 12 of the same year, D. Pedro was acclaimed as the first emperor of Brazil, with the title of D. Pedro I, being crowned on December 1, 1822.

Consequences of Independence

The Independence of Brazil was an event of great national importance, but it should be noted that few social ruptures caused by it.

Marginalized groups during the colonial period, such as enslaved and indigenous people, continued without greater rights and political participation. Slavery itself was maintained, with its legal end only in 1888.

In politics, unlike other countries on the American continent, which became republics, Brazil remained monarchist. A monarchy considered by many to be contradictory, as Brazilian independence was proclaimed by a Portuguese and Brazil continued to be commanded by Portuguese, although no longer controlled by Portugal.

Some wars took place in the territory, led by groups that did not accept the end of Portuguese rule. Conflicts occurred in the provinces of Bahia, Grão-Pará, Maranhão, Piauí, Alagoas, Sergipe and Ceará.

D. Pedro I had to hire an army of mercenaries (soldiers who fight not for a cause, but for a payment), in addition to requesting loans from England, to contain the insurgents.

Portugal recognized Brazilian independence only in 1825, with the signing of the Treaty of Peace and Alliance. For this, Brazil paid an indemnity of two million pounds sterling to the Portuguese.

Again, to get the money, it was necessary to resort to a loan from the English. However, as Portugal had debts with the British, this amount was only deducted from the debts.

Independence Day:September 7

Brazil's Independence Day is celebrated on September 7 because it is considered the symbolic moment that D. Pedro breaks the relations of subordination with Portugal.

This day is a national holiday and several Brazilian cities organize school and military parades to celebrate the date.

Video about the Independence of Brazil

How was the Independence of Brazil?See also :

- First Reign

- Questions about the Independence of Brazil

- Causes of Brazil's Independence

- Brazilian Independence Anthem

- Brazil's Independence Day