Communists, when they got down to business, always had to turn everything upside down. It is hard to find a better example than Tygodnik Powszechny. Stalin closed it so effectively from beyond the grave that the magazine ... continued to appear. Jaruzelski closed the same newspaper and even stopped publishing. But the editorial staff kept on coming to work.

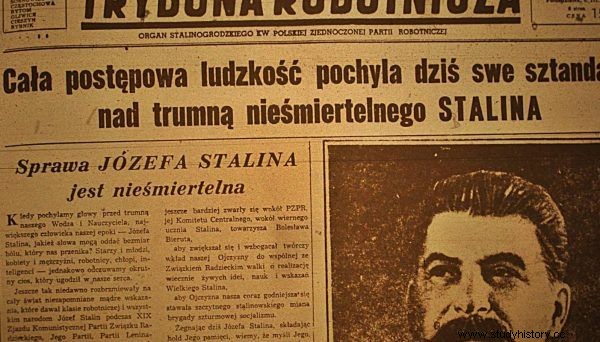

People's democracy was governed by a certain culture. For example, when the greatest leader in the history of the globe died, it was appropriate to say goodbye to him. The authorities of Katowice knew very well what was going on. Barely old Stalin's pickaxe refused to obey, and already they ran to Warsaw, asking for their city to be renamed Stalinogrod .

Oddly enough, the journalists of the only independent newspaper in Poland at that time did not have such enthusiasm. I wrote about the history of Tygodnik Powszechny a few weeks ago. Now it's time to pay some attention to the two attempts to take it down.

Stalin from beyond the grave…

After Stalin's death, the editor-in-chief of Tygodnik Powszechny, Jerzy Turowicz refused to publish a commendable text about the dictator . He also refused to admit that the death of the USSR leader was a great blow to humanity.

The Workers Stand from Stalinogrod (Katowice) praised the deceased to heaven, but Tygodnik Powszechny had no intention of following in her footsteps ...

The enraged authorities immediately ordered the publication of the letter to be stopped. The editors tried to negotiate the terms of a compromise with the ruling party. However, this was not possible in the Zelockish atmosphere that prevailed at the top of the government. The last issue of "Tygodnik" was released on March 8 .

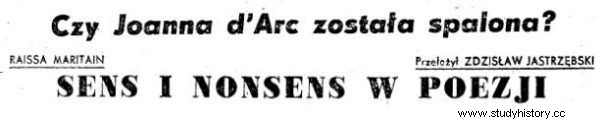

You could read about a medieval saint ("Was Joanna D'Arc Burned?"), "The Land of Troubled Tourism", and even "The meaning and nonsense in poetry". Not a word about Stalin.

The last issue of the "real" Tygodnik Powszechny.

At first it seemed that the writing would simply cease to exist. The Office for Religious Affairs led by Antoni Bida tried several variants without success.

He was tempted to agree to resume the weekly, if its editor-in-chief leaves (Turowicz) and the most virulent journalist (Stanisław Stomma). Apparently, it was even allowed to leave Turowicz in the editorial office, if he ceased to manage it. But the team denied it. And the authorities looked for a different solution.

Józefa Hennelowa, one of the then employees of Tygodnik Powszechny, tells in the book "The gene of risk was in him":

Tolo Gołubiew went to the last conversation about our being or not with the secretary of the Central Committee, Franciszek Mazur. When Gołubiew returned from her, he only said:"I smashed Tygodnik Powszechny". And the authorities took the "Tygodnik" away from us (…)

They gave our handwriting to PAX, people who have nothing to do with our environment. They published the "weekly" as if nothing had happened, under the same vignette, maintaining the same numbering. "

The next issue of Tygodnik Powszechny was published on July 10, 1953. On the surface, it looked identical to the previous ones. Nobody informed the readers of any changes. Only the line of writing seemed to be more favorable to the party. Much!

In the last issue of Tygodnik Powszechny everything was missing but Stalin ...

It has started praising socialism, criticizing spoiled youth, and driving pins to the Church . Nothing unusual. From then on, Tygodnik was published by people who were completely subordinated to the authorities. Of course, they didn't flaunt it too much, and most of the readers were fooled.

What happened to the real editorial office? Flew out onto the pavement with bans from taking up other jobs . Some were engaged in making Christmas decorations, others lived thanks to the help of the Church or donations from the Polish community. The aforementioned Józefa Hennelowa lived off the salary given by the vicar of one of Krakow's parishes - Karol Wojtyła.

Jaruzelski from the machine…

The rightful owners regained Tygodnik Powszechny after Władysław Gomułka came to power. The new first secretary wanted to please the Church. He released the Primate, handed over the weekly, pretended for a while everything would be better.

Of course it wasn't, but Tygodnik survived until 1981. Then was closed once again - automatic, like any uncertain writing during martial law.

The editors, however, played power on the nose. Maybe the magazine couldn't be published, but journalists would come to work anyway . They discussed the situation in the country, brought guests in, planned future moves. Roman Graczyk recalled:

The editorial office was literally swarming. Young and old poets, rebellious party members, bearded Solidarity activists released from boarding schools, university professors, Catholic activists from small towns (...), friends from independent scouts, beautiful women and a peasant from Liszki with a fresh supply of sausage. As a matter of fact, all this society conspired constantly against the people's power.

This is how the ferment was born, the effects of which made themselves felt a few years later. Before, during and after the Round Table Talks.