They emerged from the sea like demons, destroyed, robbed and murdered, then disappeared with the spoil, leaving ashes behind them. "From the fury of the Northmen save us, Lord," she pleaded fearfully. But God did not always listen to prayers ...

"It has been almost 350 years since we and our ancestors inhabited this charming island, and there has never been such a horror in Britain as we have now experienced at the hands of a pagan race, nor was it even thought that such an attack from the sea could occur," he wrote Alcuin, scholar and monk living in the lands of the Franks to the king of Northumbria Etelred. "Look at the church of St. Kutbert, spattered with the blood of God's priests, robbed of all its ornaments, the most venerable place of all in Britain has been left to the pagan peoples."

The blood of God's priests is spilled

Alcuin, of course, in his letters refers to the attack on Lindisfarne in 793. It was one of the most famous acts of violence committed by the Vikings, which the monk calls "wolves". This brutal attack was all the more shocking as it was here that the heart of the Christian Northumbria was beating, where Kutbert, who died in an aura of holiness in 687, was a bishop and where his remains were buried.

Among the inhabitants of medieval Europe, the Vikings looting every chance were terrible.

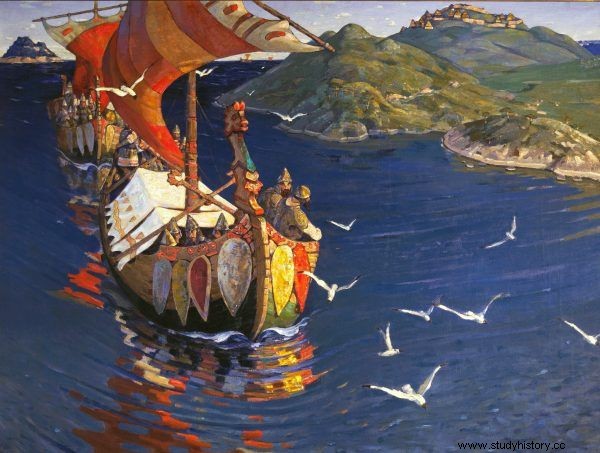

The Vikings entered the history of the British Isles at the end of the 8th century. In Chronicle of the Anglo-Saxons we read that a group of Normans landed on Portland Island in Dorset, where they were mistaken for merchants and asked to pay the toll. The unfortunate man who attributed them with good intentions has, of course, been killed. According to the chronicler, initially "pagans invaded and destroyed the coast of Britain", and in time they began to regularly venture inland.

In the years 802 and 806 they attacked the prosperous abbey on the island of Iona, with the second raid being so disastrous that the few surviving monks finally wanted to leave the island and move the abbey to Kells. However, Prior Blathmac MacFlainn and a few brothers remained there. They were ready to die in defense of the holy place - and they did not have to wait long for it. They were cut into the trunk and the prior was tortured. According to the description of the abbot of the German Reichenau:

A cursed wild crowd raced through the buildings, threatening horribly blessed husbands, and murdered the rest of the community with furious cruelty, turned to their holy father to force him to give up the precious ores, among which the bones of Saint Columbus rest [...] the saint, however, without weapons in his hands, kept his steadfast will, accustomed to resisting enemies.

One of the most famous Viking attacks was the raid on Lindisferne (the castle on the island in the photo).

A year later, the Vikings burned down numerous Galway Bay abbeys (including Inishmurray and Roscam), and in 821 Howth, County Dublin, was "plundered by pagans who had captured large numbers of women." Several years later, two fleets of invaders from the North, 60 boats each, ravaged the Cos Meath and Kildare valleys. In the description of the death of the leader of Leinster Maelciarain, which took place in 869, we read that he was betrayed by his people and handed over to the Normans, who dismembered him, and then used the severed head as a target. This event was recorded in the so-called Three Fragments of the Chronicle of Ireland .

Evil grows stronger

It was no better on the continent. In the Franconian Annals of Bertys in 842, Bishop Prudentius of Troyes described how "a Norman fleet unexpectedly raided the settlement of Quentovic at dawn, plundered it and razed it to the ground, enslaving or massacring both sexes." Emphasizing that the victims of the invaders also fell women (and possibly children) was a common way of showing the bestiality of the people of the North at the time.

In AD 843 we read that in Nantes, the Vikings "killed the bishop and many clergy of both sexes and plundered the city." The chronicler points out several times that the cruelties of the visitors from overseas were numerous. Ermentarius of Noirmoutier, abbot of Saint-Philibert de Tournus in Burgundy and author of the chronicle De translationibus et miraculis sancti Filiberti , who lived in the mid-ninth century, spoke in a similar vein about the ubiquitous Norman terror. . In it he described the Viking raids on his monastery many times:

The number of ships is increasing, the endless influx of Vikings is growing immeasurably. Everywhere Christ's people are victims of slaughter, fire and plunder. The Vikings flood everything in their path and no one is able to oppose them […]. Countless ships are sailing up the Seine, and evil grows stronger throughout the region. Rouen was ravaged, looted and burned. Paris, Beauvais and Meaux taken, the fortress of Melun razed to the ground, Chartres occupied, Evreux and Bayeux sacked, and every city enclosed in an encirclement.

With time, the invaders ventured more and more boldly inland, until in 845 they sailed up the Seine and, under the command of Ragnar, stormed Paris. The first Viking attack on the Iberian Peninsula also took place in the same period. The invaders were led by Bjorn Żelaznoboki and Hasting, who were described in Arab chronicles as "cruel people, such as had not been seen in our homeland before."

The Arab chronicler Al-Nuwayri, who lived at the turn of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, wrote that the murderous Vikings, when plundering Seville in 844, did not spare even pack animals ” . The Duald Mac Fuirbis, on the other hand, noted that "they brought with them to Ireland a great crowd of Moorish prisoners ... for a long time these blue men were in Ireland." At the same time, William the Conqueror, great-great-grandson of Rolla or Rolf, the first ruler of Normandy, changed the history of Europe by taking power in a country that his ancestors were so eager to invade and plunder.

Hornets, Wolves and Killers

Simeon of Durhan, credited with the authorship of the Historia Regum , describes Vikings with animal metaphors such as "stinging hornets" or "bloodthirsty wolves" while at the same time ascribing to them the worst crimes. "By ruthlessly looting, they turned everything to dust, trampled sacred objects with sacrilegious feet, dug up altars and plundered all church treasures," he says. "They killed some brothers, they bound some shamefully and left them naked, and drowned others at sea."

In the face of such reports, it is not surprising that the constant threat of a Viking invasion aroused also among the inhabitants of female monasteries. According to the legend of Saint Ebba, abbess of Coldingham, fearing the approaching Danes, she cut off her nose and upper lip, and the nuns encouraged them to do the same. That way, they were to avoid disgrace.

Many medieval chroniclers shared the hatred of the dreaded Vikings. Adam of Bremen, describing the Viking invasion of the Franks in 882, says that "they made entertainment with our people." On the other hand, Henry of Huntington in his Historia Anglorum characterizes visitors from the North as "swarms of bees, the cruelest of people who spare no one because of their age or sex" . Florence of Worcester also mentions numerous crimes committed by Sven, who invaded Mercia in 1013, committing "multiple acts of barbarism".

Coastal Europeans looked at the sea with fear for fear of invaders from the North.

This "lightness" in killing and torturing Christians, especially clergy, shocked historians the most. In Anglo-Saxon Chronicle we read that during the sacking of Cantenbury in 1011, Archbishop Elfeg was captured by the Vikings (the chronicler incorrectly gives the name Duncan), who was tortured by the wild fat for refusing to pay the ransom. An account of this event can be found in the Chronicle of Thietmar:

[…] a crowd of pagans surrounded him and began to put up with various weapons to kill him. When their chief Thurkil saw this from a distance, he ran quickly and shouted, "I beg you, don't do this! I am willing to give you all gold and silver, and whatever I have or in any way I will acquire, except my ship, as long as you do not commit a crime against God's anointed. " But the anger of his companions, harder than iron and rock, was not softened by his human speech; He was satisfied only with innocently shed blood, to which everyone got at once with the help of wolves skulls, a hail of stones and wooden projectiles.

Pagan beasts or warriors of their time?

Even before Knut or Sven, Ivar the Boneless was the leader in cruelty. Today it is impossible to say whether he was actually sick, or whether the nickname had a different, more metaphorical meaning, but was apparently an exceptionally cruel man . He is credited, among other things, with the murder of Saint Edmund, King of East Anglia, whom he ordered to torture and then beheaded.

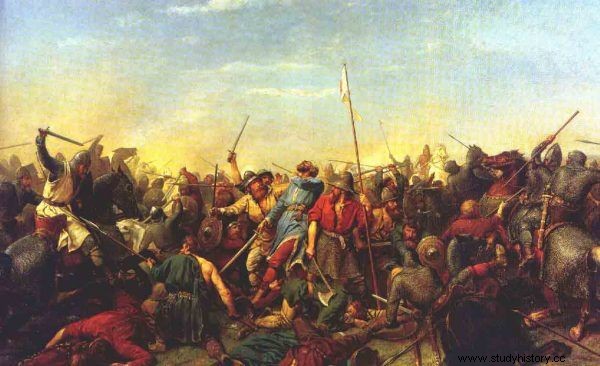

However, the king of Nortumbria Ælla did not receive the grace of holiness, who, according to legend, killed Ivar's father, the famous Ragnar Lodbrok, by throwing him into a pit full of snakes. According to the legend, Ivar, hungry for revenge, ordered him to be killed in 867 with an extremely elaborate torture - cutting out the so-called bloody eagle on his back. In 873, when the cruel ruler died, he was mentioned in the Ulster Annals as "the king of all Scandinavians in Ireland and Britain," the leader of the "great pagan army" that had conquered the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms and seized the land for over a decade.

The Battle of Stamford Bridge in 1066 is often considered the end of the Viking invasions of Great Britain.

Medieval Europeans looked with fear for the long boats that brought death and destruction. The people of the countries invaded by the Normans saw in them barbaric monsters that fell on their heads like punishment from the heavens, murdered, enslaved and plundered and what they could not rake - they turned to dust. They were alien to mercy, pity, fear of God, they committed crimes incomprehensible to medieval Christians.

Were they actually such monsters? If we consider that Charlemagne murdered 4,500 pagan Saxons in 782 for his revolt against attempts to impose Christianity on them, and the popularity of clerical murders or mutilations of relatives in the families of the Christian rulers of the era, the Vikings do not seem so terrible. Maybe it's time to undo their nasty label of cruel beasts?

Inspiration:

This article was inspired by Bernard Cornwell's novel "The Last Kingdom", which was published by Otwarte publishing house. This is the first volume of the best-selling series about the turbulent times of the Viking invasions of England in the 9th century.