Geneva Convention? Gentlemen at the controls? Forget it. During the Battle of Britain, no one thought about conventions. Did you jump out of the plane? Are you waving a white flag? Drown yourself in the sewer. Or call the U-Boat.

- Who are you? Snag or ours? (…)

- You stupid fucking motherfuckers, get me out! (...)

- As soon as you gave the smell (...) we knew immediately that you were from the RAF!

This was the dialogue between the lifeboat crew and the English Channel pilot. Despite the vulgar request for rescue, the sailors smiled friendly and immediately pulled RAF officer Geoffrey Page out of the cold water. They gave him towels, a blanket, a flask of alcohol to warm him up, and they dressed the bleeding wounds.

Speed was the key

Page was shot down on Monday August 12, 1940 in an attack on the German Dornier Do 17 bombers. He jumped out of his burning Spitfire and landed with a parachute in the water where he waited for rescue. Injured, burned and cold, he was already losing consciousness when he heard a boat circling around him and a question about his nationality. But what if he were German and spoke German? We can almost be sure that the crew would have sailed off into the blue. And when they left, they would also say: Call yourself a U-boat!

Geoffrey Page pictured in 1944. If not for the quick help of the rescue team in the summer of 1940, Page would have ended up at the bottom of the English Channel (source:public domain).

Death came quickly after the Channel, floating in the cold waters, so immediate help was crucial. The British used Coastal Command motor boats or civilian fishing boats, and it was mainly the crews of the latter who left their enemies floating in the sea.

The Germans, in turn, used rescue seaplanes that landed near the fallen ones, and their crew dragged the "bathers" aboard. Airplanes were more mobile than boats, they could quickly fly into the area of ongoing combat and land on the water when needed. Lest there was any doubt as to their purpose, the machines were painted all white, had civilian markings and very visible Red Cross marks on the wings and fuselage.

Nevertheless, they became the target of the Allied attacks. Not because they had a swastika flag painted on their tail, but because of the more obvious one - planes often won races with lifeboats and were the first to pull the survivors out of the water. They provided help, but their crews also captured British airmen. During the heaviest fighting in August and September 1940, German planes saved 72 airmen. There were probably the British among them.

The article was based on the memoirs of Witold Urbanowicz, the new edition of which has just been released by the Znak Horyzont publishing house.

Each pilot rescued from the sea raised the morale of his colleagues, and - if he was not injured - he could quickly return to the fight. On August 31, Heinz Ebeling of JG 26 first shot down a British Hurricane, but had to jump himself from a damaged Messerschmitt and landed in the Canal's water.

After half an hour, the Do 18 flying boat landed next to me, the crew of which pulled me out of the water. After delivering me to the sea rescue unit in Boulogne, I drank a full mug of cognac and ate a plate of pea soup with it . (...) [On the same day] I flew for another action (...) and managed to shoot down two more Hurricanes.

The loss of every pilot made things worse, also because it took months to train new ones. On July 14, Fighter Command ordered the fight against rescue aircraft. The German side protested against this, emphasizing that airplanes with the Red Cross emblems are protected by international law, the Geneva Convention and the customs of war.

To rescue their pilots, the Germans used, among others, Dornier Do 18 flying boats (license CC-BY-SA 4.0).

In response, the British Aviation Ministry said that "rescue" planes were under attack because they were also used for reconnaissance missions, transferring German agents off the British coast, collecting data for meteorological services and laying mines.

This was not entirely true, but the hunt for planes bearing the Red Cross emblems intensified. In response, the Germans covered the white planes with camouflage camouflage, although they left red crosses, mounted their weapons and added a fighter escort. After that, the brutality of the clashes made the Luftwaffe more acute.

The fight spread over British territory and this is where the downed airmen landed. The Germans could no longer catch their pilots and they almost always fell into enemy hands. The British survivors, in turn, quickly returned to the fight. In changed circumstances, an idea appeared and the German commanders of fighter units were consulted:

- How would you handle the order to shoot parachuting pilots?

- I would consider it murder, Herr Reichsmarschall One of them, Adolf Galland, replied to Hermann Göring.

- This is exactly what I expected from you! Göring said, but he ordered the RAF pilots to be saved in this way to be shot anyway.

Attention! You are not on the first page of the article. If you want to read from the beginning click here.

Galland refused to obey the order and forbade the firing of his subordinates, but many Luftwaffe airmen were unscrupulous. Sergeant Kazimierz Wünsche from 303 Squadron learned about it, he was shot down and had to leave the burning Hurricane. As Arkady Fiedler wrote:

Immediately after popping up, the flier did a great deal of foolishness. He opened the parachute. He should have waited. But too late he realized, and after a while the dome opened with a slight thud. Too close to the enemy.

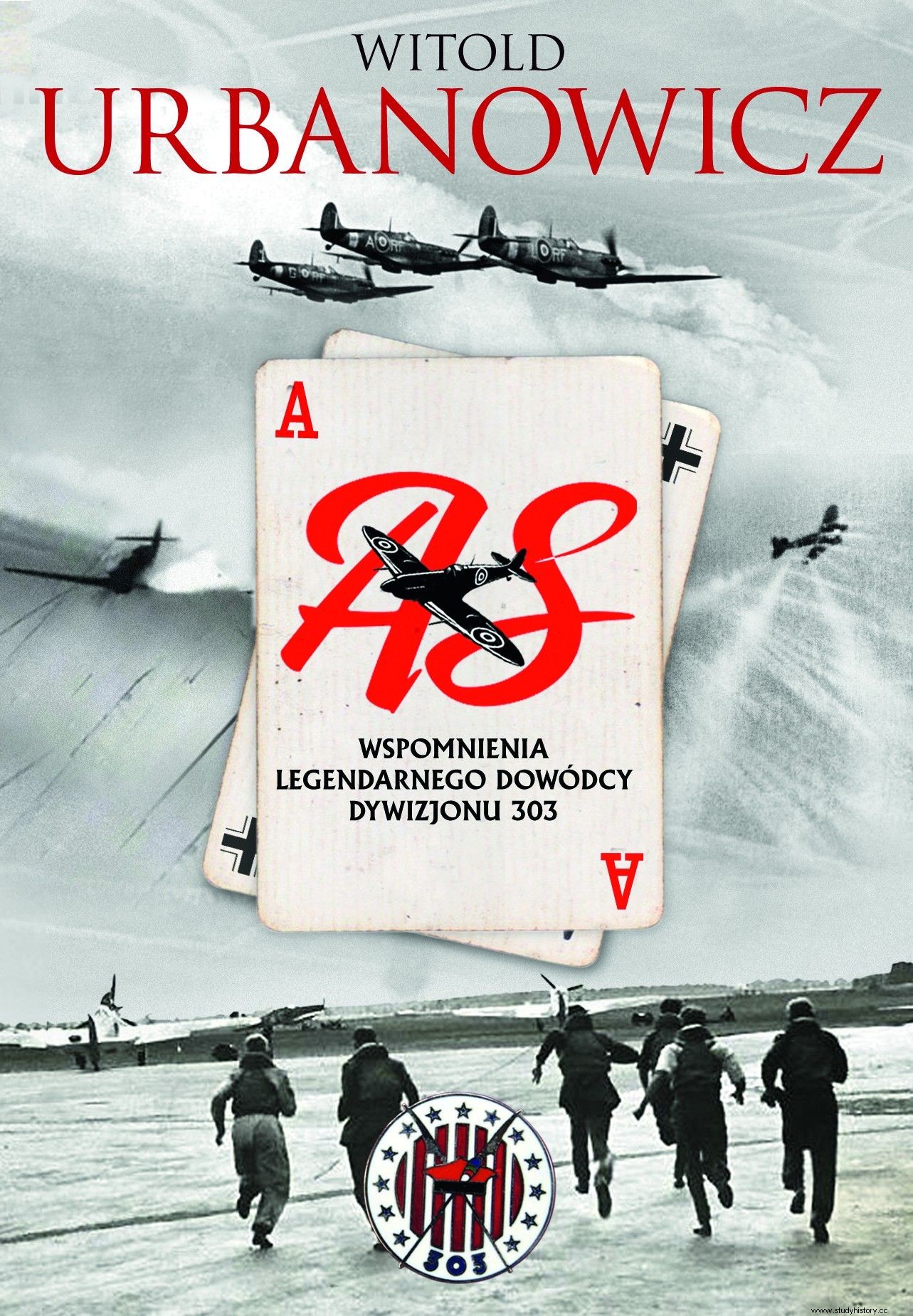

When the pilot was jumping out of the damaged plane, he had to wait as long as possible before opening the parachute. Otherwise, it became an easy target for enemy fighters. In the photo, the air fight during the Battle of Britain (photo:Puttnam; licensed public domain).

It was an enemy who recognized only the law of the jungle in its most brutal form:to kill ruthlessly, exterminate even the defenseless, exterminate the defenseless. The sergeant, dangling limply from the belts, looked up and clearly saw the two Messerschmitts approaching him. He took it as the inevitable corollary of his mistake. He was strangely indifferent and fell into a mild faint state. Apparently, the lack of oxygen at this altitude and the previous experiences (...) in the cabin worked like that.

After two minutes he came to himself. Still falling. He was alive. And Sergeant Wünsche will be alive:three Spitfires showed up nearby. They thwarted the attempts of the Messerschmitts, drove the enemy away, and now they covered the paratrooper's flight. The fighter descended safely to the ground and to a new life.

The article was based on the memoirs of Witold Urbanowicz, the new edition of which has just been released by the Znak Horyzont publishing house.

Another air pirate was immediately punished by Witold Urbanowicz, commander of the 303 Squadron. In his memoirs, he recalled the following scene from Friday, September 6, 1940:

One of the Messerschmitts attacked our hanging pilot parachute. The German was perfect for me goal, was something lower and stared, aiming at the parachute. He was just fine with the rescuer to be the pilot. He forgot about his tail. I entered from a sharp turn in the tail of him and from a distance of several dozen meters I gave several series, arranging fire on the cabin.

He must have got one of the first series, he somehow unnaturally tore up, hung limp and collapsed on the wing. I finished it with a few series. The plane caught fire, the pilot did not jump. I was afraid that the German might have shot our pilot's parachute, but the dome, gently balancing, flowed to the ground.

Roger Hall witnessed one of his colleagues who parachuted out was literally massacred by a German pilot (source:public domain).

Others were not so lucky. Roger Hall, an RAF officer, witnessed how:

flying in front of the German was shooting at something (…). Suddenly (...) I saw machine gun bullets and a cannon enter the center of the body [of a parachute airman], which on impact folds like a pocket knife blade, like a blade of grass bending under the cut of a scythe blade - he recalled.

Of course, shooting at defenseless colleagues evoked a desire for revenge and attempts to repay the beautiful for good. Such behavior happened to the Allies, they were accused of, inter alia, Polish airmen.

But they also happened to the British. Some even had the consent of their commanders. The commander of the 74th RAF Squadron, Ira Jones, made no secret of it:

I was in the habit of attacking parachute-hanging Huns which led to a lot of discussion in the casino. Some officers, graduates of Eton or Sandhurst, found my conduct unsportsmanlike. I didn't go to a good school so I didn't take that kind of objections to heart. I explained that there was a bloody war going on and that my intention was to avenge my killed colleagues.

Thanks to the bravery and sacrifice of the Allied pilots, the Battle of Britain was won. Sometimes, however, it was necessary to exceed predetermined limits in order to permanently eliminate the enemy from the fight. In the photo, Spitfire attacks the Dornierów Do 217 formation (photo:Speer; source:Bundesarchiv; lic. CC BY-SA 3.0 de).

And only sometimes, during the fierce fighting, could you see the remains of humanitarianism - for example, on Monday, September 23, 1940, two British officers swam into the sea, where the wounded German pilot Friedrich Dilthey landed. They helped the German stay afloat until the fishing boat arrived, which saved the three of them.

During the fights from July 10 to October 31, 1940, the attackers lost about 2.5 thousand. airmen killed and captured and approx. 1 thousand. injured. Defenders of approx. 550 killed and captured, approx. 500 wounded airmen and approx. 23-27 thousand. killed and 32 thousand. injured civilians and military on the ground. The free world won, and the Allied pilots were the first to show that the Third Reich could be defeated militarily.