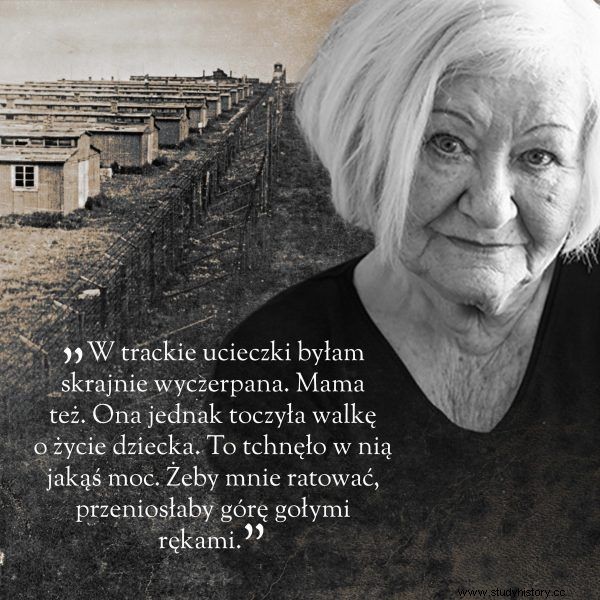

I am often asked if I am used to talking about the Holocaust. About what I've been through. About the ghettos, about the camp, about the bad Poles I met and about the cruelty of the Germans. About all the horrors of the Holocaust. Of course, these are not easy conversations. These are not easy memories. But I can come back to some things more easily, and some I would like to wipe from my memory.

Unfortunately - it cannot be done. I remember all the time…

Escape from the camp

Majdanek is such a memory that I would like to erase from my memory. Camp near Lublin, where I found myself with my mother in 1943. I have read many books in my life about the nightmare of concentration camps, but I never had the courage to reach for a book about Majdanek ... And I will never do it again.

The memories of the women who survived are shocking…

Because what for? After all, I saw it all with my own eyes. I know how it was there. I know how hell was . Hunger, violence, lousy barracks. Diseases, rags . Human life worth less than a slice of bread. Ubiquitous death.

My mother knew. She had no illusions. She knew how it all had to end. I also sensed it. I understood that there was only one way to end this all. And I told my mother about it openly. Me, a little girl.

- Mom, I want to live so badly. But I know it's impossible. I know I'm going to die.

I guess Mom was just crazy with despair. You have children, so you can imagine what must have been going on in her soul. What she had to go through. It was black despair. And then she decided that it didn't have to be that way. That we are not doomed to such an end. That he must fight for his life. Yours and mine.

Mom made a plan. She stole a canvas cape from Ukrainian watchmen. Very dark, I think black. Don't ask how she managed it. I do not know. Taking advantage of the inattention of the guards, she crept to the barbed wire. She noticed there was a slight gap in one place.

Next to it, she found a large stick on the ground with which a guard tortured a man and then dumped him there. Mum hid the stick well. And she waited patiently for the opportunity. The night has finally come. It was raining heavily, nothing was visible except the jets of water falling from the sky. Perfect conditions for an escape.

Mom woke me up. I saw that he had a cloak under his arm.

"You told me you wanted to live," she said. - If so, be consistent and don't fuss. Come on, let's go…

We left the barracks. In such weather, the guards who usually walked along the barbed wire hid in their quarters. Even if they were outside, they wouldn't see much. In the pouring rain, we huddled towards the wires. Mum, with the help of the stick she took out of the hiding place, enlarged the gap in the wires. Just enough for me to squeeze through. She was walking over me. Unfortunately, she hurt herself painfully and the barbed wire torn her body nasty. The most important thing, however, was that it worked. We were on the other side, outside the camp!

But that was just the beginning. The easiest part of the escape. I raised my head and looked around. On the horizon, the glow of the morning aurora. It was dawn. A dusty gray plowed field stretched out before us in the twilight. And nothing more. It seemed to me that this field is endless. Somewhere, far away, it was blurring in the dark. Every now and then the spotlights from the watchtowers swept around them. Mom prepared for it. She covered us with a black cape and we began to crawl under its cover.

Meter by meter. Centimeter by centimeter. Far away from the wires. As the spotlight approached us, we froze under our cloak. A pillar of light passed over us and continued on. My mom was squeezing me the whole time, pulling my hand. The rain was pouring down harder and I was freezing to the bone. The plowed ground turned to thick, sticky mud. And it was invading my mouth, my nose, my eyes. I was covered in it all.

I thought we crawled forever. Every move - in the heavy, sticky ground - was a monstrous effort. I was terribly tired. I was losing my strength, almost fainting. I started to protest. I was just a child after all.

- Too bad, let them kill me. I don't care, I said.

And I wanted to get up! If I did, they'd kill us immediately. They mowed a series of machine guns. My brave mother always knew what to do in such situations. She didn't lose her cold blood, she didn't scream. She just gripped my hair tightly and pressed me to the ground. And she began to drag me on. With her free hand she shoved the ground. She pulled her knees up, pushed herself off with her legs. She crawled through that terrible mud. Slowly, relentlessly, forward. I heard her breath wheezing from the exertion.

Majdanek in June 1944

It hurt me terribly, but I was already indifferent to everything. Semi-conscious. I was malnourished, extremely exhausted. Mum too. However, she was fighting for the life of her own child. It gave her some power. To save me, she would have moved the mountain with her bare hands. She was just amazing.

Rescue?

We only rested when we crawled to the first bushes. Being out of reach of those devilish spotlights. Instinctively, I touched my head - I was horrified to discover that a tuft had been thinned from my lush hair. I was left with a bald cake in the middle of my head! But alive for that. That was all that mattered.

There was a wooden house relatively nearby. Through the windows covered with curtains, we saw the light of an oil lamp smoldering inside. We took a risk and knocked on the door. After all, nothing worse than Majdanek could not have happened to us. Besides, we had no choice.

We had to seek help. We were terribly muddy. Hands, legs, head - all in the mud. Soaked to a dry thread. We were swayed from exhaustion and hunger. The morning was freezing, if we had stayed outside, we certainly wouldn't have survived.

The door was opened by a man, a Pole. It turned out he was a railwayman. Due to the proximity of Majdanek and his profession, the Germans frequently checked him at home. Especially if someone escaped from the camp. So it was not a safe place. But he was a decent man. Despite his fear of the Germans, he let us in.

- Get yourself tidy, he said. "We'll give you food, but then you must be on your way." Otherwise, we are all in danger of death.

Of course, my mother understood the situation of these people. She couldn't expect a stranger to put his and his family's life at risk for her . A railwayman left us and directed us towards the nearest station. He explained where the trains slow down on the tracks. He advised us to jump into a moving car. In this way, leave the camp as soon as possible, escape the pursuit.

Majdanek in June 1944

We did so too. Soon a passenger train came and we were inside. During the stops, we hid to the toilet, and when the train started, we left. After a few hours of driving, we entered the station ... We found ourselves in Warsaw again. Our hometown. The city where I grew up and spent the first carefree years of my life.

It was, however, a completely different city.

Good people and bad people

Throughout the war, I had to lie. Just to survive. During the occupation I had different birth records, different surnames. And each time I had to tell people I met to tell incredible things about myself. This was left to me long after the war, when I was studying. And then I worked on TV. I used to travel a lot on long-distance trains then. During the journey, people loosen their tongues and like to talk about themselves. I also had to talk about it. Back then, I was creating hand-drawn stories in which I performed almost all the jobs in the world. It was very fun for me.

To this day, I have a false date of birth in my ID - the one I had in my last German Kennkarte. Only one year is correct. Mom was better because with the end of the war ... she had lost ten years. She had such a date of birth entered in the Kennkarte, on the basis of which she obtained an ID card after the war. For the woman, of course, it was very beneficial, but there were also disadvantages. Ten years later than she should have retired.

When my mother died in 1992, I was in a dilemma what date to carve out on the tombstone. In the end, I came to the conclusion that since she had been deducting those ten years all her life, I would not be adding them to her after she died. Especially since my stepfather was lying in the same grave and, according to false papers, they were of the same year. Interestingly, she never admitted this innocent fraud to him.

Władek, however, was not beaten in the dark and just before his death, when we were talking in private, he confessed to me:

- Zosia, you know, your mother thinks that I am stupider than in reality. It is impossible for her to be as old as she says. If that were the case, she couldn't have done so much in her life. Just please don't make her wrong. I don't want her to know that I can guess the truth.

Mom was reluctant to talk about the war. She didn't want to go back to it.

- It was, it passed - with these words she usually cut off all attempts to talk about it. - We won, and we live. Dot. What's to talk about?

Auntie too. My cousin Bronek had to be forced by force to get something out of him. Only I had no qualms about this type of conversation. After the war, my mother tried to force me not to talk about my Jewish origins. In July 1946, after the Kielce pogrom, she reminded me of it for the second time. Her wartime and post-war trauma was extremely strong.

The article is an excerpt from the book by Anna Herbich Girls survivors. True stories

But I told my mother that I would not hide from the world that I was Jewish. Because something bad is hiding, and I don't see anything wrong with my background. And indeed - I never hid it. Despite this, in the People's Republic of Poland I did not experience any persecution because of my origin. So much so that when in 1968 my husband Jerzy Żukowski was thrown out of the television, they didn't touch me.I got married in 1961. I have a son, Maciej, and one granddaughter, Agata. My husband was a press journalist, then he emigrated to Brazil. He lived there for four years, but he wanted to come back. However, the communists did not allow it. It was only his father's friends, writers, who started contacts at the Ministry of Culture and thanks to that he was granted a visa. When he returned to Poland, he started working on television. We met there. He died in 2006. My father-in-law was named Wilhelm Raort. He was a famous figure, editor of the Lviv satirical magazine Szczutek. It was the equivalent of the Warsaw "Szpilki".

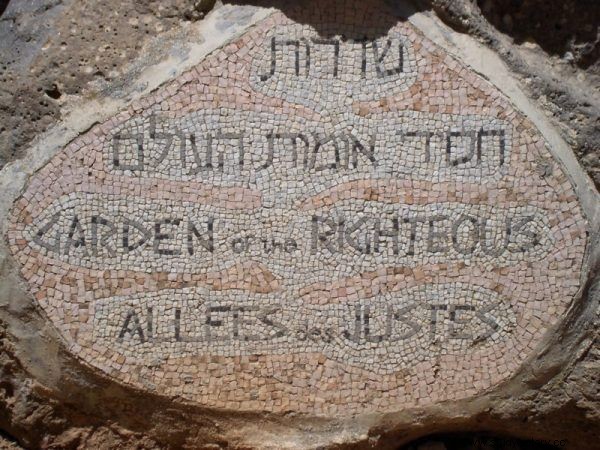

I belong to the Association of the Children of the Holocaust. One of the basic forms of our activity is helping the Righteous Among the Nations. These people risked their own and their families' lives to save their Jewish neighbors. Now we are doing something for them. Many of them live in difficult conditions, receive penny pensions or do not get them at all. We help them deal with various official and health matters.

We give them parcels during holidays. The first lady I went to with such a package told me at the door that she was expecting a visit from her granddaughter. She asked me not to reveal the nature of my visit to her. She offered to introduce me as her friend. Well, I agreed to it.

When my granddaughter left, the lady tried to explain herself:

- You know, my family does not know that I helped Jews during the war. Because I made the decision properly on behalf of the whole family. If the Germans caught us, they'd kill us all. In fact, I was risking their lives for complete strangers. I never had the courage to tell them about it.

Yad Vashem Garden of the Righteous Among the Nations

It was the first time I realized how risky it was. How incredible heroism the Righteous showed. I didn't think about it before. I asked myself if it were the other way around, if the Germans were killing ethnic Poles and saving Jews, would I be able to save someone else's life at the cost of my family? Would I take such a risk? I wish you could. But are you sure…? They were just holy people.

I do not condemn those who took money in return for hiding a family or a Jewish child. After all, they were often very poor people. Moreover, there was a war and food was hard to come by. They couldn't afford to keep a few more of their own. Often a second family. So the Jews simply contributed to the budget. Not all who took the money mistreated the Jews who were hiding there.

We should condemn, and definitely, those who led the traced Jews to the gendarmes in order to get a kilo of sugar from the Germans. Those who blackmailed the Jews, those who denounced them. People who take advantage of other people's misfortune to get rich. They were able to turn the life of the Jews into a real hell, a series of torments. They are responsible for incredible suffering and a sea of blood. I know it well, because I have dealt with blackmailers many times myself. We have the right to judge these people very harshly. There is no excuse for them.

There was a whole range of attitudes in occupied Poland. Both among Poles and Jews. These are all very complicated matters. Far from the black and white simplifications and schemes that are so popular today. The worst thing is the generalizations. Each case should be investigated and assessed individually. How many people, so many different stories. Great things happened in Poland, but terrible things also happened. Our task is to tell the truth about them. The whole truth. No matter how painful it is.