The industrial revolution changed the world - though not always for the better. For millions of children, it meant poverty and the need to seek employment. The little workers massively populated the factories, mines and roofs of English houses, and the tasks they were performing had nothing to do with safety and hygiene.

An eighteen-year-old miner with ten years of experience? A "retired" sixteenth birthday chimney sweep? A factory worker coming back after a 13-hour shift to ... play with a doll? What sounds like an exceptionally gloomy joke today was a gray reality for 18th and 19th century English children. As he concludes in the book Children of the Industrial Revolution Katarzyna Nowak:

Industrial England's power was built by small hands that quickly changed thread spools, cleared chimney bottlenecks, hauled coal carts in the darkness of the mines. (...) Child labor became the norm with the rapid development of industry, which needed cheap labor, and with the impoverishment of families who could not live off their parents' wages alone.

From the perspective of the employers at the time, the youngest were the ideal "engine of progress". They were paid little or not at all, it was easy to subjugate them - if not by goodness then by force, and in the event of an accident or death from exhaustion, they could easily be replaced . And it is for this reason that small workers were often entrusted with the most difficult and dangerous jobs. What professions did the children "specialize" in? And what were they at risk of?

Slaves of the underworld

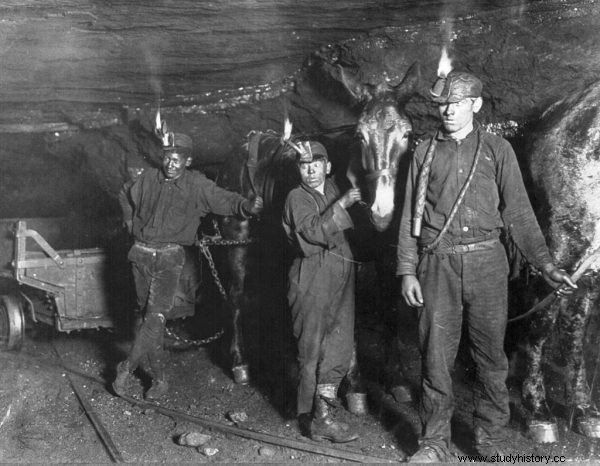

Even today, the work of miners is considered to be one of the most difficult and risky. Two hundred years ago, the situation of people who earned their bread by mining raw materials from under the surface was even worse. A commissioner examining the conditions in the Worsley coal mine in 1833 noted with horror that:" the hardest work in the worst room of the worst factory is easier , less cruel and demoralizing than working underground. ”

Children were particularly eagerly employed in the mines. Illustrative photo.

And the deeper the corridors drilled, the more dramatic the situation became. In the narrow, horizontal tunnels that reached two kilometers below the earth's surface, you had to squat or lie down. Meanwhile, it was much easier for small, agile children to fit in there - that is why the owners of the mine willingly employed young adepts in the art of coal mining.

It also took less effort to transport them downstairs - the minors were lighter, so they could be lowered on a rope. Some of the little miners probably did not even realize that death was waiting for them there. And this came in many ways:from an explosion of a gas lamp, to collapsing a corridor and drowning, to being hit by a car. In the 19th century, five-year-olds opened the shafts of a Yorkshire coal mine! For such young children, being underground was not only dangerous but also traumatizing. These are the first days of small miners' work described by Peter Kirby:

At first the little victims brought into the mines fought and screamed in terror into the darkness, but there were people brutal enough to make the children submit . After a few tries, they became docile and apathetic, ready to engage in any slave occupation that was imposed on them.

The professional work of the youngest was very often slave - especially when orphans were given "employment". At that time, the employer was limited to providing his little subordinates with the absolute minimum necessary to survive. The children received modest meals, a roof over their heads (often leaky) and a bed that they had to share with another underage worker. At most they could only dream of a salary.

In the maze of London chimneys

As dangerous as going deep underground was climbing over roofs and inside chimneys. And also this work - due to its specific nature - was eagerly commissioned to children.

The tragedy that happened in 1666, when London burst into flames, taught the city's inhabitants the importance of fire safety. For this reason, new regulations were introduced:henceforth the chimneys were built narrow and winding, which was to prevent the rapid spread of fire. In this form, however, they required more frequent cleaning. And although chimney sweeps had many types of brushes at their disposal (including a mechanical one), it was widely believed that the best suited for this purpose was ... a small, dexterous boy.

The "living brush" had to be properly prepared for work:children had to be nailed in the feet to make them climb faster. Usually, during the first days, the little ones torn the skin off their elbows and knees in a tight maze - to harden the skin, so salt was rubbed into it . It was not until 1788 that a law was passed, pursuant to which the employers had to provide the chimney sweeps with appropriate "protective" clothing. It also prohibited the employment of children under the age of eight.

However, it was sometimes different with the observance of these provisions. The more that inside the chimney it was best to move naked. Hardly anyone realized then that the consequence of such practices is a serious and extremely unpleasant disease - scrotal cancer, which developed within a few years after "retirement". This happened as early as in their teens, maturing boys simply stopped fitting into holes 22 by 34 centimeters - unless of course they lived to by then.

Little boys were - at least in the opinion of the British in the 19th century - excellent chimney sweep material. Illustrative photo.

The little chimney sweeps were rather focused on the current threats. And these were not lacking. As Katarzyna Nowak describes in her book:“a narrow passage or a sudden turn is a trap. If [the child - ed. M.P.] gets stuck and runs out of air, he will die - the boy sent after him is unlikely to have time to free him before he suffocates ".

Mad Hatter

Compared to other "child" professions, the work of a hatter seemed to be much less risky. Ultimately, the young apprentice sent to the workshop where headgear was made was not threatened with death by asphyxiation, drowning or crushing. But there was another danger for him - all the more sinister because… invisible.

Like chimney sweeps suffering from scrotal cancer, hat makers also had their occupational disease - saying that someone is crazy like a hatter did not come out of nowhere !! After several years of work, it was easy to recognize a specialist in this profession by red fingers, trembling hands, nervous behavior, damaged hair and nails and missing teeth.

All of this was a grim side effect of the mercury poisoning that was used for felting wool in Victorian studios. And since the performance of this simple task did not require any special qualifications, the students who were apprentices to the master were often exposed to inhaling the fumes of the toxic element. In extreme cases, it resulted in serious neurological disorders and even death.

Hat-making was not the only "plot" of the textile industry in which children were employed. Hundreds of thousands of minors found jobs in textile factories, wool mills, etc. It was a heavy piece of bread. The kids spent 13-14 hours a day at the machines . It was not until 1802 that the length of the shift was limited to 12 hours a day, and after the next three decades - to 9. The minimum age of the employed - 9 years - was established only in 1874; It was raised to 11 nearly 20 years later. Previously, it often happened that preschoolers stood by the production line.

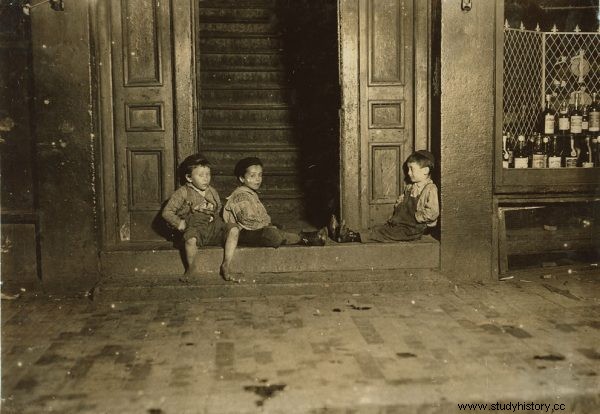

Most often, children from shelters or poorer families were sent to work. Illustrative photo.

The youngest, only 5- or 6-year-old, were cleaning and cleaning devices - usually they were not even turned off, so accidents were not difficult. The older ones guarded the spindles, changed the thread spools, and performed other simple, unqualified activities. Their employment in factories was favored by the mechanization of work and the division of the production process into parts - it was no longer necessary to teach the worker a whole complicated series of tasks. It was enough to train him briefly in one specific activity.

Nightmare factories

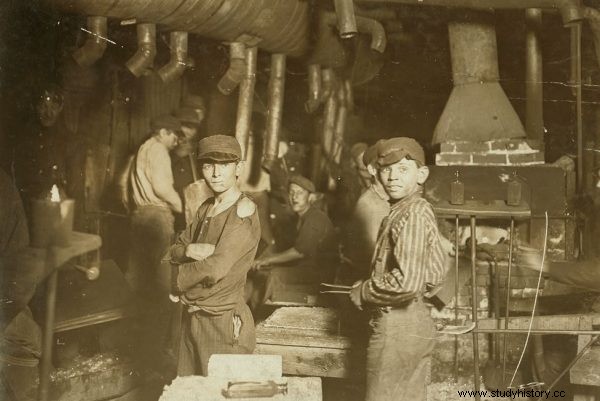

Children who worked beyond their strength, beaten and starved, deprived of care or free time were seriously ill. They suffered from underweight, stunted growth, curvature of the spine. And so their work in textile factories was - compared to the fate of small workers from pottery workshops or glassworks - quite safe.

The red-hot stoves made it difficult to breathe, the temperature was unbearably high, resulting in eye problems and lung ailments. In addition, there were burns, cuts (especially in the glass industry) and general exhaustion. However, no one was particularly concerned about it - you couldn't just give up one fifth of the employees just because they were under the age of 13 . Yes, in the book Children of the Industrial Revolution Katarzyna Nowak describes the fate of underage workers in Victorian England:

Children get sick. Poor diet, dire hygienic conditions and hard work drive them to the brink of exhaustion. If one of them falls at work and is unable to get up after a few kicks, they are put on a wheelbarrow and taken to the barracks. If he survives, he goes back to work. If not, a quick burial is organized.

Work in factories and manufacturing plants carried the risk of accidents and serious diseases. Illustrative photo.

Factory owners don't care too much. These are the conditions, and if they want to achieve something in this business, they must act according to the rules of art. If something is in abundance in nineteenth-century England, it is children . So it is cheaper to bring in new ones than to heal the already sick.

As Eric Hobsbawm notes:"The Great Revolution of 1789-1848 was not so much a triumph for 'industry' as such as for capitalist industry." This one, in turn, was focused primarily on profit - at any cost. And that the children had to pay it? Well, in many countries, adults today are not too bothered by it. Because although Europe and North America stopped this shameful practice, still every ninth child in the world goes to work every day instead of going to school ...

Bibliography:

- Goose N., Honeyman K. (eds.), Childhood and Child Labor in Industrial England:Diversity and Agency, 1750-1914 , Routledge 2016.

- Hobsbawm E., Age of Revolution 1789-1848 , Publishing House of Krytyki Polityczna 2014.

- Honeyman K., Child Workers in England, 1780–1820:Parish Apprentices and the Making of the Early Industrial Labor Force , Ashgate Publishing 2007.

- Nowak K., Children of the industrial revolution , Horizon 2019 sign.

- Rahikainen M., Centuries of Child Labor. European Experiences from the Seventeenth to the Twentieth Century , Ashgate 2004.

- Thompson C., From the Cradle to the Coalmine:The Story of Children in Welsh Mines , University of Wales Press 2014.

Get to know the stories of the youngest participants of the industrial revolution: