Saint Jerome taught that "the one who has been cleansed by baptism does not have to bathe a second time." He urged women to spoil their natural beauty out of concern for their souls by "deliberate neglect". Many medieval aristocrats followed his advice. Were Polish rulers also at odds with hygiene?

The Medieval Church distinguished between the hygienic and medical needs of bathing and the entertainment and pleasures that were often taken in baths. He did not call for excessive self-care. In the early Middle Ages, bathing was even prohibited on Sundays and public holidays. All this so as not to distract from matters of the spirit. “What are we to say of those who keep their dresses smelling good; […] That my hair would be curled; they eat spices to smell from their mouths; they clutch their necks and legs, and all their clothes are made of the blood and sweat of the poor "- preacher Maciej from Książ thundered from the pulpit.

Dirty body - clean soul

The example often came from above, that is, from saints and blessed ascetics and ascetics falling into the love of dirt. They were imitated by Polish medieval rulers, especially in the 13th century. Two of our duchesses and saints became the embodiment of the fashion for far-reaching restraint:Kinga, wife of Bolesław the Chaste, the prince of Kraków and Sandomierz, and Jadwiga, wife of the prince of Wrocław, Henryk the Bearded.

The first of them, as we read in her life, did not give up her virginity even in her marriage. She probably did not attach great importance to her beauty, since " when she was praised for her beauty, she bruised her face and smeared it ". Moreover, "she never took any relief in a tub or in a bath, nor did she wash her face with any water except on the occasion of communion or in dire need".

Saint Jadwiga of Silesia not only applied terrifying hygienic practices, but also carried them out on her own grandson, Bolesław, and in front of her daughter-in-law. The picture shows a 15th-century miniature.

In turn, the Silesian duchess, after fulfilling the obligation to extend the family, forced her husband to end her relationship and hid in a monastery. She lived there like a nun, she was mortified and starved. She didn't care at all to wash a thick layer of mud off her bare feet from time to time. Instead, it found an application for the water in which the nun's feet were washed. Namely ... "she poured her face and head and bathed her granddaughters in the same water". And if she was already washing her face, then "when she came to the towels, whose hands [the nuns] rubbed, where they were the dirtiest, she put them on her eyes and mouth."

I sprinkle acana into the water, the bath is already hot!

These dissuasive examples do not change the fact that baths are mentioned in the oldest accounts of the history of the Slavic region in the Middle Ages. At that time, using them was considered the basic body care treatment. They were available to almost everyone - prices in the cities were not excessive. The royal family, the staroste, the owner of the baths, members of the guilds and members of the city council were entitled to free baths.

They were washed with lye, and later also with soap - in the 14th century, the first soap makers were already operating in the vicinity of Płock. Baths were taken in tubs and tubs. The aristocracy used herbs and rose petals to give the body a pleasant fragrance. The wealthiest ones arranged their own private "bathing rooms".

The arrangement of the court baths between the 10th and 13th centuries certainly did not resemble the primitive bathhouses or dugout baths used by the lower layers. In the suburbs, the baths were almost the size of residential houses !! This is evidenced by the excavations in Gniezno and Gdańsk, where baths with dimensions of 2.35 x 5 and 4.5 x 4.5 meters, respectively, were discovered. And what was it like to take a bath in such a home medieval spa? The pictorial reconstruction can be found in the book "Life in a Medieval Castle" by Joseph and Frances Gies:

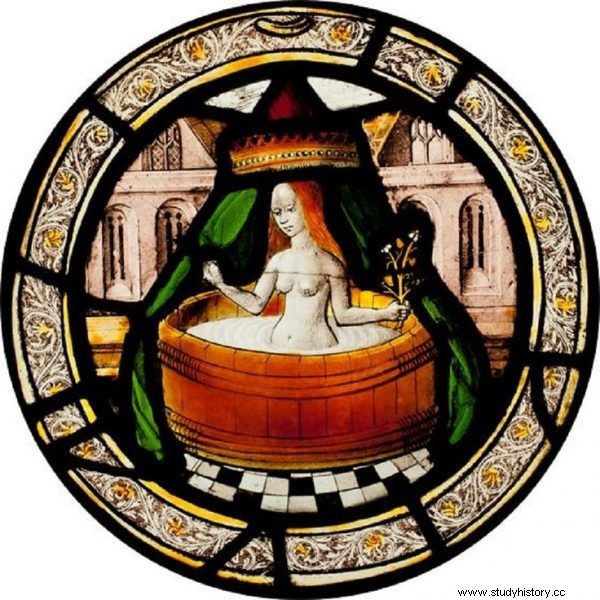

Baths were taken in a wooden tub, covered with a tent or canopy, and sent with linen for convenience. A lot also depended on the weather - on warm days the bath tub was often placed in the garden, in cold weather - in the chamber, next to the fire. On the other hand, when the master was traveling, the tub accompanied him along the way with a special servant who prepared everything.

A similar description can be found in the advice for pages and service written in the mid-15th century by John Russell, steward at the court of the Duke of Gloucester. In The Book of Good Manners, he devoted a whole separate chapter to bathing. What should a well-trained servant do if the master wanted to "clean his body clean"?

Bath in a tub under a canopy. An English mosaic from the early 16th century.

First, he had to cover the tub by hanging sheets soaked in the scent of fresh herbs and flowers from the ceiling. He also brought sponges on which his master could lean on or sit in the tub, and he prepared a sheet to cover. He then washed the master using a soft sponge and a bowl full of hot decoction of fresh herbs, then rinsed him with warm rose water. Finally he was wiping him dry and taking him to bed to prevent catching a cold.

Queen on a stay

Contrary to popular belief, the wealthy of the Middle Ages did not need to be reminded of bathing or beauty treatments. Often, when going on a longer journey, they would take a wooden tub with them. This was done by both the English king Jan Bez Earth and the Polish king Władysław Jagiełło, who used to carry his favorite horse-shaped tub .

Crowned heads could also afford a permanent bathroom in the palace. Such a bathing house was, for example, in the residence of Henry III in Westminster. The royal couple could freely use the supplied running water, also hot. It was taken from tanks filled with water from jugs heated in a special boiler.

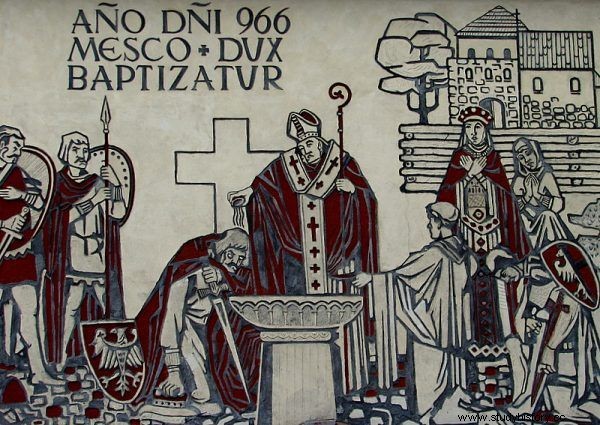

Dobrawa not only prompted Mieszko to pour baptism water over his head. She also liked to use water herself, for example in the sauna. Contemporary mural in the picture.

It was no different in the case of the Piasts and the Jagiellons. And for them, regular baths and visits to the baths were an indispensable element of hygiene. The bathing preferences of Dobrawa, the wife of Mieszko I, were described in the book "Iron Ladies" by Kamil Janicki. He emphasized that the duchess probably had a private sauna in which there were stone stoves and water tanks.

Dobrawa was not the only Polish ruler who was passionate about bathing. It is said that in Busko, Queen Jadwiga herself used healing ablutions at the Norbertine nuns. It is possible that the water for the queen, rich in bromine, iodine, iron and hydrogen sulphide, was further enriched with thyme, mistletoe, periwinkle or seven-tan. Certainly the smell was intoxicating, and the ritual itself was very pleasant, the only question is, why did Jadwiga need so much trouble?

The Queen acted ... for the sake of the continuity of the family. Let us remind you that she gave birth to her first and only child, a daughter who died a few weeks after giving birth, after many years of fruitless relationship with Jagiełło. Bathing in healing waters could - according to the beliefs of the time - remedy this "vileness of infertility". This opinion was confirmed in any case by Bishop Jan Radlica, the queen's confidant and an excellent physician who served her father.

Clean teeth and ... "Venus's chamber"

Cleanliness was also taken into account with the matters of the alcove in mind. The concepts of courtly love and chivalry in force in the higher spheres made the degree of attractiveness dependent on personal hygiene. In many romances and collections of lessons from the era it was emphasized that physical closeness is all the more pleasant the less repulsive the smell of lovers . Erasmus of Rotterdam recommended that the teeth be cleaned with a mastic toothpick, a feather or a chicken bone. In the 12th century, the famous Trotula recommended that ladies use nut shells and rinse their mouths with wine with a little salt. Sage and pastes made of various herbs and spices were also used.

In the Middle Ages, hair removal agents and perfumes were already used. The latter were made from flower oils, herbs and spices. Mieszka probably introduced them to Dobrawa. They were certainly used - also in the alcove - by Bolesław Chrobry's wife, Emnilda, who influenced her husband's political decisions with a whole arsenal of love tricks. What beauty treatments could she use to maintain her husband's lust? The authors of Life in a Medieval Castle shed some light on them:

The lady could arrange her hair using the mirror. [...] Despite clear opposition from preachers and moral writers, the ladies used various cosmetics:sheep fat, pink and bleach for the skin, which gave it pink and white color.

Nothing like fragrances and entertainment in a luxurious bath.

For the sake of a successful relationship, it was advisable that the other party should not avoid taking a bath. Jagiełło was a lover of sitting in the tub and demanded it wherever he went. The bills for the repairs and investments of the baths he used have been preserved. A great clean man who liked to use the baths (also in the morning, despite the strict prohibitions of the medic), was also Casimir the Great.

The ruler's chastity, beyond his unmistakable royal authority, may have been one of the reasons for his enormous success with the ladies. But that's another story…

Bibliography:

- Culture of medieval Poland 10th-13th centuries , ed. Jerzy Dowiat, PIW 1985.

- Katherine Ashenburg, The History of Dirt , crowd. Aleksandra Górska, Bellona 2009.

- Kamil Janicki, Ladies of Iron , Horizon 2015 sign.

- Jarosław Nikodem, Jadwiga - King of Poland, Ossolineum 2009.

- Joseph and Frances Gies, Life in a Medieval Castle , crowd. Jakub Janik, Znak Horyzont 2017.

- Jacques Le Goff, Nicolas Truong, History of the body in the Middle Ages , crowd. Ireenusz Kania, Reader 2006.

- Piotr Skarga, Lives of Saints of the Old and New Order , Warsaw 1857.

- Florian Jaroszewicz, Mother of Saints Poland or the lives of saints, blessed, reverend, worldly, pious Poles and Polish women , Printing House of Stanisław Stachowicz 1767.