Chimera, in ancient Greek mythology, was a hybrid animal that had the body of a goat, the tail of a serpent, and the head of a lion, and breathed fire. We have already seen in a previous article that its origin may be related to the fires that have been burning for millennia on Mount Yanartaş. By extension it is called chimeric to any fantastic animal composed of parts of others.

One of these chimerical animals of antiquity is the Serpopardo. Actually the term is modern, invented by researchers to refer to an ornamental motif whose name has not reached our days by any source. He is called Serpopardo because he was represented with the body of what appears to be a leopard and a long neck similar to a snake. And usually two by two, with their necks intertwined.

In Egypt it is depicted on cosmetic palettes from the end of the Predynastic Period of Egypt (just around the time of the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt by Pharaoh Narmer, around 3200-3000 BC). In Mesopotamia it has been found mainly on cylinder seals, more or less from the same time and from about two centuries earlier.

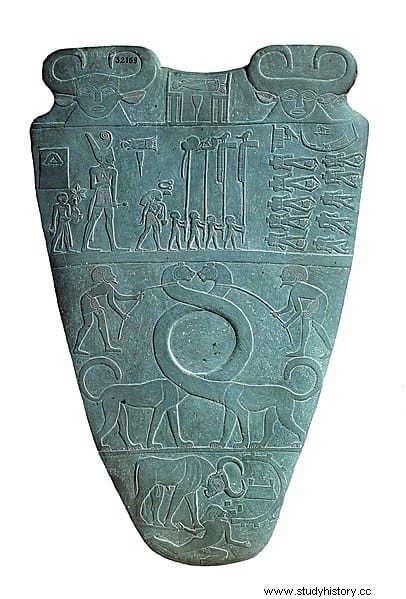

Precisely one of the most outstanding examples appears in the so-called Narmer Palette. It is a slate plate decorated with bas-reliefs whose function was to serve as a support for ointments and creams (similar to painters' palettes). It was discovered in 1897 in the temple of Horus in Hierakonpolis (at the same time as the King Scorpion's macehead) and it represents the pharaoh Narmer, possibly as the winner in the war of unification of Egypt.

On the back of the palette are depicted two serpopards with their necks intertwined, which leads some researchers to interpret them as the union of Upper and Lower Egypt. In addition, the almost circular part formed by both necks was used as a container to grind galena or malachite and create the kohl , the eye makeup used in ancient Egypt.

Although at first glance serpopards might appear to be nothing more than stylized giraffes (as some believe the mythological Chinese Qilin to be), they are actually felines that are depicted with an unusually long neck. Some scholars believe that the body is actually that of a lioness and not a leopard, based on the shape of the head and the representation of the hair on the end of the tail. However, Carolyn Graves-Brown believes that the serpopard probably derives from the misinterpretation of giraffe fossils.

Curiously, it is the only animal that is represented in ancient Egypt attacking other animals, as in the so-called Palette of the Two Dogs that is preserved in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. In it we see two serpopards licking a gazelle while other felines with similar bodies, in the lower part, are dedicated to hunting them.

For this reason, some researchers believe that long necks are probably nothing more than an exaggeration used as a decorative element, to frame an artistic and functional motif. Perhaps that explains why no document could be found that mentions the name of these curious chimerical animals.

In Mesopotamia, serpopards are always represented in pairs and in symmetrical compositions. On the contrary, in Egypt they can appear alone, as on the front of the Hierakonpolis Palette (in the Louvre), where a solitary serpopard can be seen, while two giraffes appear on the reverse.

Sylvain Vassant believes that the fact that the motif came from Mesopotamia and Egypt may give a clue to its meaning. In Mesopotamia the two intertwined serpopards would represent the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, while in Egypt they would represent the upper course and the lower course of the Nile.

A variant appears in some Egyptian tombs in which the head of the animal is that of a serpent instead of a leopard (or lioness). This variety is known as sedja (which comes to mean something like he who travels in the distance ).