The reader would be surprised at how few grams of fiction that we have needed to add to the classical sources to create this evocation of a peculiar single combat (monomachia; pl. monomachiae ) Iberian. The episode, completely real, is known to us by various authors, interested above all in the picturesqueness of the situation and who, consequently, dwell on aspects as accessory as those we have used in our brief narration (Liv. XXVIII, 21, 6 et seq.; Val. Max. 9.11 ext. 1; Sil. Pun . XVI, 277-591); additionally, they avoid any effort of historical investigation, reducing the episode to the condition of anecdote.

In all cases, our sources speak of “gladiatorial combat ”, valuing the confrontation according to his own –and distant– cultural experience. The gladiatorial fights developed in the Roman world a ludic value that had little to do with the funerary meaning that we glimpse in its confused origins. In our case, we find ourselves before a sample of the original content of what in the future would have to be a magnificent show:the confrontation of Orsua and his cousin, named Corbis , was part of the games organized in 206 B.C. by P. Cornelius Scipio in honor of his father and his uncle, who died five years ago during one more of the actions waged on the Iberian front of the Second Punic War . According to Livy, Scipio celebrated these "gladiatorial" combats as a munus funerary, that is, as a posthumous satisfaction of the duties contracted with his ancestors; and he did it in the city of Cartago Nova , strategic nodal point of his campaigns in Eastern Andalusia since he took control of it in 209 BC. by audacious sleight of hand.

However, this interpretation is problematic in several ways. If piety was Scipio's sole aim, how to explain the five-year hiatus between the death of his ancestors and the celebration of the munus? ? Questions of opportunity could be adduced in a war situation, but content with such an explanation would imply ignoring the peremptory condition that funeral ceremonies had in Roman religion, intended above all to appease the vengeful spirits of the deceased. It is not the only exceptional element of the exhibition that concerns us:Livio makes an effort to make it clear that the type of men who fought there was not “of the kind that lanistas usually present [N.B.:those in charge of the sale and/or training of gladiators in the Roman world]”; Quite the contrary, they faced each other of their own free will, pretending to show off their courage, to please the general who had organized the games, or, in the exceptional case of Corbis and Orsua that concerns us here, to resolve internal dynastic quarrels under the gaze of Scipio ( XXVIII, 21, 2-6). For his part, Silius Italicus highlights how "those who faced each other with the sword did not do so because of a crime or crimes that threatened life, but because of courage and a vehement passion to achieve glory" (pun . XVI, vv. 529-530).

So, our munus it is very special, and it involves individuals from different cultural backgrounds who possibly had different understandings of the event they were taking part in. Although the organizer was Roman, and although the spectators, mostly of identical origin, shared his perplexity at that unusual display of fratricidal madness (Liv. XXVIII, 21, 6), the contenders were very far from what we generally understand by “gladiator”, and we could quite legitimately ask ourselves what it meant for them to fight to the death against the victorious Scipio; or ask ourselves, in other words, what Orsua aspired to when he confronted his cousin.

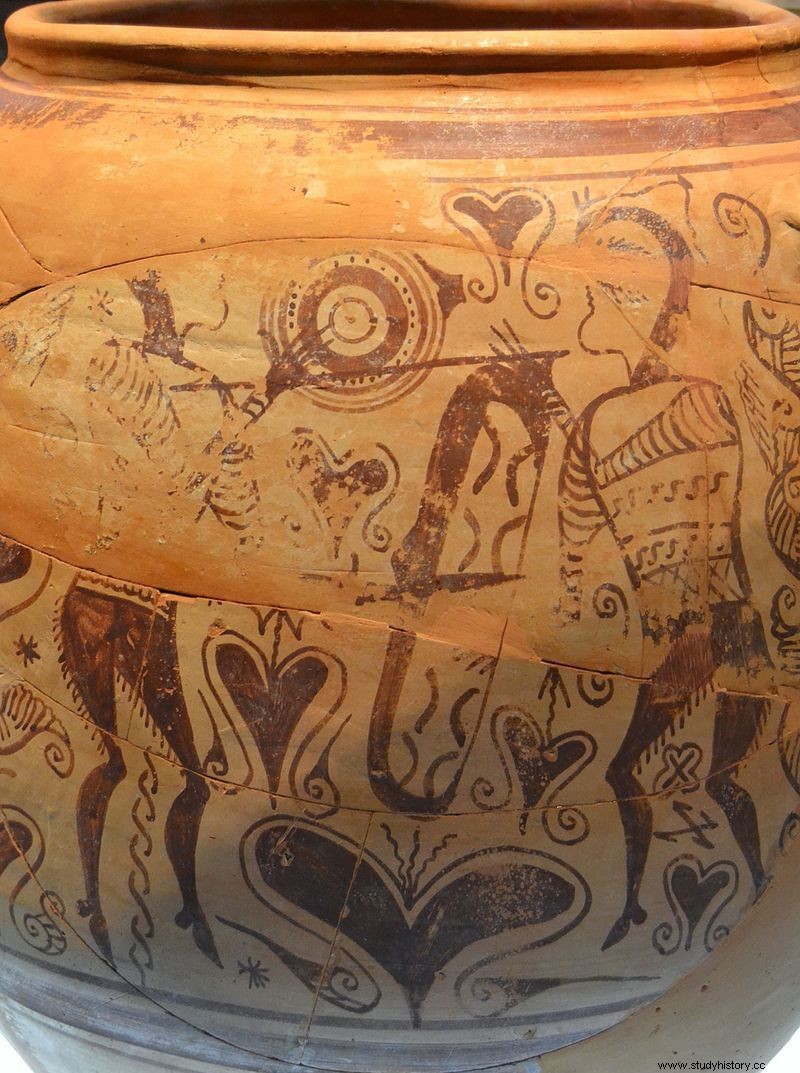

An answer to these questions could only be offered from an understanding of the internal phenomena that affected Iberian societies at the end of the 3rd century. These had been subjected to a process of transformation accelerated by the evolution of Mediterranean affairs, which attracted the attention of Carthage and Rome to their territory. , political giants of the time involved in a titanic struggle of unprecedented proportions. Under the pressure of the conflicting powers, the previous local balances were blown up, and for a long time, Iberia was immersed in a maelstrom of conflicts from which it was impossible to stay out. The instability brought with it a modification of the qualities that were required of the rulers. Above all, these had to be guarantors of the protection of their communities in a hectic war context, and as such they are represented in the dominant iconography of the time, significantly different from that of previous moments. Thus, both ceramics and sculpture will be invaded by representations of weapons and combat, by daily violence, in short, to which only warrior-like chiefs could respond.

Within these coordinates, we can understand that Corbis and Orsua are incapable of admitting any resolution of their litigation that does not go through the explicit display of their force (Val. Max. 9.11 ext . 1). They both fight for power over their community, and they do so on multiple levels. The most obvious is material:direct elimination of an opponent leads to command; however, exterminating adversaries would serve no purpose without the consent of the governed. There is, therefore, a second plane in which they fight:the ideological one, because the winner will have managed to demonstrate his warrior excellence and, with it, his suitability to guarantee the survival of his community. The winner, finally, will obtain a third endorsement of his authority, namely, the acquiescence of Scipio, whose honorary recognition as judge of the dispute is probably implicit in the choice of the funerary games organized by him as the ideal setting to celebrate the combat. . In this sense, we could think that the winner expects recognition from the man who represented the visible face of Rome in Iberia, thus forging a personal relationship of fides (personal commitment of a sacrosanct nature) that legitimizes from the outside, but also from the inside, whoever emerges victorious from the fight.

Sources diverge widely on the outcome of the contest , although we can directly rule out the version offered by Silius Italicus. In it, both contenders die at the same time in a pathetic way, in an outcome that aims to build a bridge with the fight between Eteocles and Polynicies in the Thebaid of Estacio and that, therefore, has more of an intertextual game than of reality. On the other hand, the version of Valerius Maximus seems to derive from that of Livy, with which we will ultimately have to content ourselves if it satisfy our curiosity about trade:"The elder [Corbis] easily overcame the blind strength of the younger" (Liv. XXVIII, 21, 10). So, we leave Orsua in the dust, confirming with Livio how great are the evils that the desire for power unleashes among mortals.

Bibliography

Bendala Galán, M. (2015), Children of lightning. The Barcas and the Carthaginian domain in the Iberian Peninsula, Madrid.

Blázquez Martínez, J. M. (1995), "Possible pre-Roman precedents of Roman gladiatorial combat in the Iberian Peninsula", in Álvarez Martínez, J. Mª.; Enríquez Navascués, J. J. (eds.), The amphitheater in Roman Hispania. Proceedings of the International Colloquium held in Mérida from November 26 to 28, 1992 , Merida, pp. 31-43.

Blázquez Martínez, J. Mª.; Herrero Montero, S. (1993), “Funeral ritual and status social:Roman gladiatorial combats in the Iberian Peninsula”, Veleia 10, p. 71-84.

Canto de Gregorio, A.Mª. (1999), “Ilorci , Scipionis rogus (Pliny, NH III, 9) and some problems of the Second Punic War in Hispania”, Rivista Storica dell’Antichità, 29, p. 127-167.

García-Bellido, Mª. P. (2000-2001), “Rome and provincial monetary systems. Roman coins minted in Hispania in the Second Punic War”, Zephyrus, 53-54, p. 551-577.

García Cardiel, J. (2016), The discourses of power in the Iberian world of the southeast (7th-1st centuries BC) , Madrid.

Quesada, F. (2016), “Los Escipiones, generals de Roma”, in Bendala Galán, M. (ed.), Los Escipiones. Rome conquers Hispania [Catalogue of the exhibition held at the Archaeological Museum of Madrid, Alcalá de Henares, February to September 2016], Madrid, pp. 69-88.

Roddaz, J.M. (1998), “Les Scipions et l’Hispanie”, Revue des Études Anciennes 100 (1-2), p. 341-358.