The German inlet of Messines was an obvious target of the British since 1915 already. The capture of Messines Ridge was vital as its possession by the Germans afforded the latter an absolute view of the British positions at great depth. In the case of Messines, the term "ridge" seems overly generous as it was a series of low ridges about 40-70 m high. Nevertheless, in an otherwise completely flat area, it provided him with a significant tactical, if not strategic, advantage. who owned it.

Of course the British leadership was aware of the problem and as early as 1915 had begun to plan the occupation of the Messines Ridge. For this purpose, in July 1915, the idea of undermining the German location was put forward , by digging a series of galleries underground and trapping them with explosives at the height of the German defense line, and in February 1916 work began.

Preparations

By the end of 1916 15 galleries had been completed, below Messine Ridge and filled with explosives. Others would follow. The British commander of the 2nd Army which was guarding the front in the area of Messines, General Herbert Plummer encouraged the effort and requested the laying of additional "mines", as the underminings were then called.

Having drawn up his plan of attack and having received Haig's approval, Plummer asked his pioneers to have everything ready by June 7, 1917. Altogether the plan called for undermining the German front at 25 points. Ultimately 22 subversions were completed. The longest gallery was 658 m long, while the largest amount of explosives – 43.45 tons – was placed in the 408 m long gallery at Saint-Eloy. Of these "mines", 19 exploded on the day of the attack. Two were blown up during a storm in 1955 and one still stands ready to spread death, lost underground.

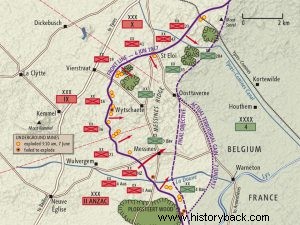

The British attack was to be carried out by the 2nd Army . For this purpose the army was endowed with three Army Corps (SS), the X , the IX SS and the II SS ANZAC (Australian New Zealand SS – ANZ SS). XIV was a reserve of the 2nd Army SS. Each British MP had three brigades, each of which had four battalions. In the attack, 148 infantry battalions, the SS organics, were deployed in the first echelon with another 48 being kept in immediate reserve.

The 2nd Tank Brigade was also made available for direct support of the infantry with the A and B Tank Battalions, each with 38 Mark IV tanks. For such a local character, a tactical attack was assembled and a surprising number of cannons. A total of 2,266 guns were allocated , from 18pdr plains to beastly 15in howitzers. This volume of artillery was gradually moved to the area of Messines along with 144,000 tons of ammunition so as not to be detected by the Germans. Also on the first day of the battle around 300 British aircraft were available of every type in the region, compared to less than half of German.

Retardation and arrogance

Against these impressive forces, the German forces lagged behind dramatically. From 1916, the Messina sector was guarded by the German XIX SS and the II Bavarian SS (B. SS). The first was commanded by General von Laffert and the second commanded by General von Stetten. The German high command took very seriously the information about an imminent British attack and steps were taken to strengthen the sector. The Germans had 5 MPs while two more were available in the sector.

Laffert and Staten insisted, however, that there was no danger of a direct British attack. Laffert even stated that he was confident that his artillery was capable of crushing any British attack that might occur, as he had about 640 guns and howitzers . Laffert also appeared confident that his vanguards had successfully neutralized all attempts by their British counterparts to undermine the German front line. It was a fallacy worse than the first.

The outbreak of fire

In Messines, Plummer's preliminary bombardment had already begun on May 31 and gradually increased in intensity. German front line troops were isolated as neither food nor supplies could get through to the rear . Due to the extensive use of chemicals by the British, the suffering Germans were forced to wear anti-suffocation masks for hours, flirting between panic, suffocation and burnt lungs.

On June 3, by order of Plummer, the bombardment intensified so that the Germans would believe that the attack would take place that day, but also to force the German artillery to respond. At the same time, the British set fire to the forests within the attack sector to provide cover for the Germans.

At 02.30 on the morning of June 7, Plummer had his breakfast with his staff and then everyone took their places. The British general was a little late in going to the observatory that had been constructed. The 60-year-old general had locked himself in his office. There he knelt down and prayed fervently for a few minutes. Then he went to his seat and waited for the Zero hour which was set for 03.10.

When the earth was torn apart...

By 02.50 all the officers responsible for detonating the mines were also in their positions. The firing wires had been checked. Everything was ready for the pact of fire and death. Only the Germans had not suspected what awaited them. By 03.00 the British assault units were in the advanced trenches from where they would launch.

Suddenly, the cannon fire ceased as if by some magical hand and a deathly silence reigned over the entire sector. Only whispers and some men's prayers could be heard with difficulty. Even the aircraft that had previously flown low to cover the sound of approaching British tanks had disappeared from the dark sky.

As the first glimmers of twilight began to emerge the Germans, alarmed by the sudden quiet, began to fire flares. On 03.09, however, hell broke loose in the broken land of Flanders. The first mines were detonated seven seconds earlier. Next came the "mines" on hill 60 at the northern end, in the X SS sector.

The sensation was shocking. The earth, badly wounded by the hand of men, rose many meters high and then fell again in a pandemonium of fire, smoke and screams of human beings. The column of smoke and fire from the explosion on Hill 60 is estimated to have reached a height of over 120 m. This was followed by the detonation of the "mine" at Saint Eloi and the "mines" in the IX SS sector. A total of 423,730 kilograms of explosives were detonated, killing thousands of German soldiers.

The "mines" were detonated within 19 seconds. Those Germans who survived or were not buried alive suffered a terrible shock. Others disdained, others believed that a catastrophic earthquake had occurred. But before they could come to their senses, the roar of the British guns followed, which they fired according to the prepared plan.

Immediately 80,000 British came out of the trenches and moved towards what was left of the German positions. The British suffered more from the low visibility due to the explosions than from the German resistance. Those German soldiers fit to fight threw white and green flares into the air requesting artillery support. But the German artillery had also taken crushing blows and was unable to respond strongly enough, to say the least. So those German infantry who were still alive and tried to resist were quickly exterminated.

At the top…

The British forces continued their advance and occupied the contested ridge. The time was approaching 05.00 and already Plummer's men had broken through the first two lines of defense of the Germans. Following this success the British forces rested for two hours. At 07.00 in the morning everything was ready for the continuation of the attack. At this time the rolling barrage of artillery began again and the infantry moved with confidence and the feeling of victory, against the next German line of defense.

The Germans tried to resist but by 0900 hours, less than six hours after the attack had begun, the German defenses had collapsed across the site and five German divisions, if not completely destroyed, had suffered overwhelming losses and could not to be considered warworthy now.

The German general whose hopes were dashed in the worst way was already a mental wreck . With this mentality it would probably be better if he was immediately relieved of his duties. But this did not happen and fatally Laffert made his next mistake ordering a counterattack with his two reserve divisions. These forces had just arrived. Nevertheless, the desperate Laffert decided to throw them into battle immediately not to support his collapsing line, as would be logical, but to carry out a counter-attack.

The German counterattack was launched at 13.45 and the result was as expected. The German artillery tried, without success, to support the counter-attack and so the unfortunate Germans fell into the barrage of British machine guns and were literally mowed down. After that the British rushed against the last German defense line which they occupied until 18.00.