In 1715 the Turkish danger again began to be felt on the eastern borders of the Habsburg Empire. Turkish ambitions had been revived since 1711, when Mehmet Pasha with 260,000 men defeated Peter the Great's 40,000 men at the Battle of Prutus. Always following the same expansionist policy, the Turks, violating the treaty of Karlovic, attacked the Venetian possessions in Greece in 1714.

The Venetian defense collapsed quickly and soon the whole of the Peloponnese returned to the possession of the Ottomans. It was obvious that their next target was the imperial territories in the Balkans. However, the Empire was not the first to declare war.

The new emperor Charles sent a diplomatic document to Constantinople asking for the sultan's undertaking that he was not going to question Karlovich's treaty, so far as his country was concerned at least. The Sultan did not even deign to answer. Instead of an answer, he unleashed his Tatar horsemen on imperial territory. So on May 15, 1716 the new war was a fact.

Prince Eugene

The best general of the Habsburgs, Prince Eugene of Savoy was from the beginning an advocate of the new war. Thanks to the laurels he had received from his glorious action on the battlefields from 1682 to 1715, against the Ottomans and the French, he assumed, naturally, the command of the army for the war against the Turks.

Evgenios immediately developed great activity. He secured the support of most of the German princes, and even the pope. Money was collected, a new type of weapons and supplies were procured, and from the summer of 1716 troops began to assemble on the frontier. Evgenios took over the administration the same summer. His goal was the recapture of Belgrade.

Eugene had only 60,000 men. But his men were highly trained and most of them experienced warriors, veterans of the war of the Spanish Succession. The prince knew that the Turks had at least twice as many troops against him, while they had reinforced the garrisons of all their border fortresses, including Belgrade.

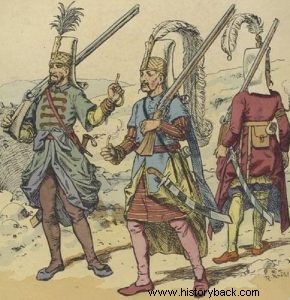

The grand vizier Silahdar Ali Pasha had at his disposal 30,000 stout horsemen, 40,000 janissaries and 50,000 irregular infantry and cavalry. This huge army was already stationed in Belgrade.

Petrovaradin

Eugene had naturally begun to gather information about the enemy. Knowing that the Turks had enormous forces and taking into account that the construction of the riverboats, with which he hoped to control the course of the Danube, had not been completed, Eugene decided to initially adopt a defensive stance.

Based at Petrovaradin (present-day Novi Sad, Serbia), he would wait there for the enemy to face him with his army covered by the cannons of the city walls. The Turks actually invaded first.

With Kurd Pasha's corps in the vanguard – 10,000 men – the Turkish army cautiously advanced. On August 2 Kurd Pasha's men faced General Palfy's Austrian outposts – 3,000 men. The triple Turks attacked and managed to push back the Imperials.

But the survivors of Palfy returned to Petrovaradin and notified Eugene, who in turn prepared to face the enemy. Elated by his success, the grand vizier moved his army, in two phalanxes, towards Petrovaradin. His intention was to lay siege to the city, which if it fell into his hands would deprive the Imperials of their main base in the region.

The battle begins

On 4 August the first phalanx of the Turkish army – 63,000 men – arrived near the city and encamped. The Turkish commander planned to attack at first light the next day. Eugene, however, never gave him the opportunity to do so. Well before dawn the Imperial army was ready to attack. All the previous night, Eugene was preparing his surprise attack.

The decision was his and he didn't even discuss it with his officers. At 07.00 in the morning his cannons began to "cheer up" the still sleeping Turks. The drums beat and the imperial regiments unfurled the flags in the cool morning air. The double-headed eagle spread its wings again, ready to devour the crescent moon. With a slow step the imperial infantry steadily marched against the Turkish positions.

The cavalry covered his advance. mobility was observed in the Turkish positions. Hastily the soldiers of the Ottoman army hastened to take up arms and form their ranks. Before long, the heavy Turkish guns also began to fire against the advancing imperials.

Eugene carefully observed the enemy's movements, uncoordinated movements, inspired by the local initiative of each officer. He would use his infantry as the first echelon of attack. As soon as his infantry broke through the enemy's defensive line he would throw his cavalry into the attack, on the same axis of attack. In a few moments the imperial infantry had reached a distance of about 100 meters from the Turkish positions.

Then the janissaries en masse formed a mass and with swords in hand and shouting terrible cries rushed against the Imperials. The Imperial infantry calmly awaited them and as soon as they got within 20 paces - 15 meters - they opened fire on them en masse.

A cloud of smoke covered the Turks. The screams of death and agony of thousands of janissaries were also lost in it. Some of them, miraculously passing through the Austrian barrage unscathed, fell furiously upon the Imperial infantry, slaughtering many men.

The cavalry is coming...

But soon they too were exterminated up to one of the bayonets of Eugene's men. The battle had taken a very fierce turn. No prisoners were taken on either side.

Gradually Eugene's men managed to suffocate the Turks, to break the enemy lines, allowing the imperial cavalry to enter the battle in turn. It was the finishing blow.

With trumpets sounding the charge, the imperial cuirassiers with swords raised fell like demons upon the weary Turks. The lighter imperial cavalry maneuvered and charged into the flanks of the Turkish cavalry while other cavalry divisions engaged it.

In just a few minutes it was all over. The Janissaries were slaughtered, and the Imperial infantry entered the enemy camp. And the cuirassiers, after destroying the Turkish infantry, now dealt with the Turkish cavalry. Soon the Ottoman cavalry had also fled.

Revenge

In less than two hours the one Turkish phalanx was gone. More than 30,000 Turks, including the grand vizier, lay dead across the entire battlefield. “We did not capture more than 20 prisoners. The men demanded their blood and slaughtered them all," wrote an officer of Eugene.

It couldn't happen any other way. And this was not due to the resistance offered by the Turks, but to the findings of Eugene's men, as soon as they entered the Ottoman camp.

To their astonishment the soldiers saw their colleagues, who had been captured earlier, being crucified, or pierced with iron hooks, or horribly mutilated, burned, and beaten to death. Faced with this spectacle, and given the opportunity to avenge their fellow soldiers, the victorious soldiers would have been unlikely to treat the Turkish captives kindly.

Even Eugene before such a spectacle was so enraged that when he arrested spies and scouts of the Turks, Serbs and Vlachs in nationality, he ordered them to be beaten.