Antonio de Oliveira Salazar (1889-1970) was a lawyer, university professor and president of the Council of Ministers of Portugal from 1933 to 1968.

Salazar was responsible for the consolidation of the Estado Novo and for the ideological implantation of the regime, Salazarism.

Biography

Salazar was born in the city of Vimieiro, on April 28, 1889. He spent his childhood in this rural location, whose father helped to negotiate properties.

Upon finishing primary school, he went to the seminary of Viseu and there he would remain eight more years, when he would decide to embrace the secular life and not the religious one.

Academic Education

Thus, he entered the University of Coimbra, where he studied Law, and joined the Academic Center for Christian Democracy. His political background includes the encyclicals of Pope Leo XIII (1810-1903) on the Social Doctrine of the Church and the works of French Charles Maurras (1868-1952).

Salazar writes numerous articles in Catholic newspapers and gives lectures defending the condition of a Catholic to be a republican, something that is not welcomed among monarchists. Equally, he attacks socialism and parliamentarism, which he considered decadent.

He is approved in the competition for professor of Economics at the University of Coimbra and draws the government's attention by writing a series of articles on the economic situation in Portugal.

Political Career

Salazar's experience as a politician begins in 1921 when he is elected deputy for the Catholic party. He only attends one parliamentary session, and returns to Coimbra three days later.

Through his texts on economics he was invited, in 1926, to be Minister of Finance. However, he remains in office for only five days, as he has not met all of his conditions.

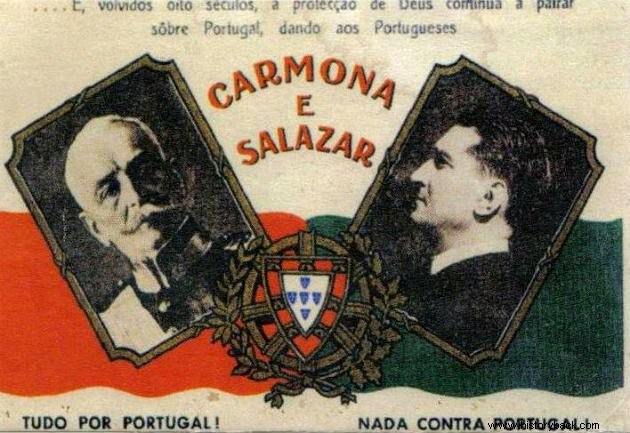

He will return to office in 1928, with the blessing of President Oscar Carmona (1869-1951), who will make him a super-minister, where Salazar has the last word on the budgets of all ministries.

In 1930 he founded his own party, the União Nacional, which would be the only party allowed during his government.

Once he has consolidated his place in the government, he sometimes accumulates positions such as the Ministry of Colonies and gains more and more support by pointing out a political path that mixes a military and civilian government.

He displeases several supporters of the more conservative and monarchical right by moving away from the discussion on the restoration of the monarchy.

President of the Council of Ministers

Either way, his prestige grows and he manages to approve the Constitution of 1933. This Magna Carta would give full powers to the president of the Council of Ministers, a position he held until he was victimized by a stroke in 1968.

Salazar would never fully recover and until his death in 1970 he thought he was still in charge of Portugal.

His government was marked by a lack of political and civil liberties, continuation of colonialist policy, collaboration with the West and a pragmatic approach to Spain.

The Salazar regime caused the immigration of millions of Portuguese and would be overthrown in 1974 with the Carnation Revolution.

Government

Salazar's government was marked by authoritarian, anti-parliamentary, anti-liberal and anti-communist ideas, a mixture between fascism and social Catholicism.

The government was governed by the Constitution of 1933 and bicameral with a National Assembly and the Corporate Chamber. The right to strike and the formation of political parties were prohibited.

The President of the Republic was a military man elected by the population and who appointed the president of the Council of Ministers, a function that Salazar always exercised.

It was a personal regime, centered on its founder and not on a party as was the case with Hitler and Mussolini. Therefore, it receives the name of Salazarismo .

In a famous speech delivered in Braga on May 28, 1936, Salazar summarizes the ideology of his government:

See also:Salazarism in PortugalCivil Rights

Individual freedoms were diminished, as the Estado Novo ended freedom of association and union expression. Media censorship is instituted.

In 1933, the Surveillance and State Defense Police was created to monitor citizenship. (PVDE). In 1945, the name was changed and the International State Defense Police was born. (PIDE). It could carry out detentions of up to six months, carry out searches without warrants and leave the detainee incommunicado.

Likewise, civil servants should swear an oath of repudiation of communism upon taking office.

Economy

Salazar defended an economy planned based on the State, but controlled by several autarchies (unions, unions, workers' corporations).

Another sector that grew was tourism, both domestic and foreign. The Portuguese beaches and climate attracted Europeans. As for the Portuguese, they were able to benefit from state-subsidized vacations and thus travel.

Despite encouraging rural and agricultural life as an ideal of life, industrialization took place slowly, especially in the 1960s. From 1958 to 1973, the highest growth rates were recorded in Portugal, reaching 7% per year.

This happened because there was a turning point in the economic policy defended by Marcelo Caetano (1906-1980), who would be Salazar's successor.

Foreign Policy

Salazar's foreign policy spans an enormous period of time, but the keynote has always been to keep Portugal isolated from liberal currents and from any outside interference.

World War II

Due to the trauma that the sending of Portuguese troops during the First War supposed, Salazar decided for neutrality from the first hour. Even so, he cedes bases in the Azores to be used by Americans and British.

Lisbon becomes a major spy center and the starting point for thousands of refugees hoping to obtain a visa.

Salazar and Franco

Portugal saw the Spanish Republic as a danger and when the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) began, Salazar recognized the government of General Francisco Franco.

The Portuguese government gave aid to the nationalist side led by Franco. It delivered Republicans who crossed borders, facilitated communications with the United States, and even encouraged the creation of a battalion of volunteers.

During World War II, Salazar sought to ensure Spain's neutrality, as he feared that conflict could reach the country. In this way, the leaders meet and sign the Iberian Pact, in 1939, when the two nations commit to staying out of the dispute.

Despite being ideologically close, personally, the two dictators couldn't be more different. Salazar was a university professor, while Franco was a military man. Despite this, the two understood each other on relevant issues.

When the colonial wars begin, Franco will provide Salazar with logistical help, ordering war material from Germany, but passing it on to Salazar.

See also:Francoism in SpainColonial Wars

After the Second World War, the UN started to defend the people's right of self-determination and, thus, pressured nations to grant independence to their colonies.

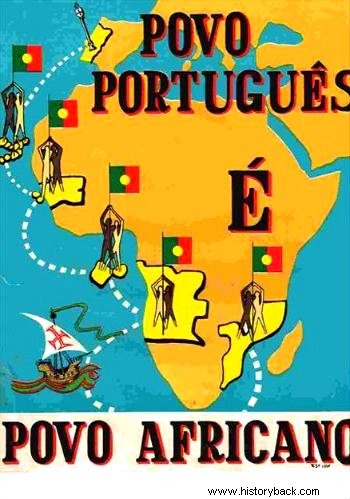

Salazar does not respond to the request. It changes the status of colonies to "overseas provinces" and grants Portuguese citizenship to all inhabitants.

He carries out numerous improvement works and encourages the immigration of Portuguese to African possessions.

Likewise, he carries out an intense propaganda extolling the brotherhood and racial democracy of Portuguese colonization.

For this, he uses the ideas of Gilberto Freyre in order to justify the mixture of races of the Portuguese colonizer as opposed to the English.

Unsuccessfully, he proceeds to violently repress every attempt at sedition, sending troops to fight in Angola and Mozambique.

See also:End of the Portuguese Empire in AfricaCuriosities

- Despite cultivating an image of being single and chaste, Salazar had his affairs carefully hidden from the general public.

- In his birthplace, in Vimeiro, is the inscription " Here was born Dr. Oliveira Salazar, a gentleman who ruled and stole nothing ".

Read more:

- Fascism

- Totalitarianism

- Civil War

- Totalitarian Regimes in Europe