The period of Terror (1792-1794), during the French Revolution, was marked by religious and political persecution, civil wars, and executions by guillotine.

At that time, France was being led by the Jacobins, considered the most radical among the revolutionaries, and therefore this period is also known as the "Jacobin Terror".

Features of Terror

In 1793, France had established the republican regime and was threatened by countries such as England, the Russian Empire and the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Internally, different political currents such as the Girondins, Jacobins and émigré nobles fought for power.

Thus, the Convention, which governed the country, adopted exceptional measures and suspended the Constitution of the First Republic and handed over the government to the Committee of Public Safety.

In this committee, there are the most radical members, called Jacobins, who pass the Law of Suspects, on September 17, 1793, which was to be in force for ten months.

This law allowed the arrest of any citizen, male or female, who was suspected of conspiring against the French Revolution.

The period of the Terror made victims of all social conditions and the most famous guillotined were King Louis XVI and his wife, Queen Marie Antoinette, both in 1793.

The symbol of this era, without a doubt, was the guillotine. This machine was recovered by the physician Joseph Guillotin (1738-1814) who considered it a less cruel method than the gallows or decapitation. During the period of the Terror more than 15,000 deaths were recorded by this instrument.

War of the Vendee

The War of the Vendée (1793-1796) or Wars of the West was a peasant counterrevolutionary movement.

In the French region of the Vendee, peasants were dissatisfied with the course of the Revolution and the institution of the Republic. They were called “whites” by the republicans, and for their part, these were the “blues”.

Peasants felt forgotten by the Republic that had promised equality, but taxes continued to rise. Likewise, when priests who had not sworn to the Constitution were banned from saying Mass, there was great discontent.

Thus, the population takes up arms under the motto "For God and for the King". In this way, the movement is seen as a major threat by the central government and the repression was violent.

The conflict between whites and blues lasted three years and an estimated 200,000 people died. Once the rebel army was defeated, the republicans proceeded to destroy villages and fields, set fire to forests and kill livestock.

The aim was to give an exemplary punishment so that counterrevolutionary ideas would not spread across France.

See also:Terrorism:definition, attacks and terrorist groupsReligious terror

The Jacobin terror did not spare the religious who refused to swear to the Civil Constitution of the Clergy. For them, several laws were enacted that provided for imprisonment and fines. Finally, the Law of Exile was passed on August 14, 1792, and about 400 priests had to leave France.

Likewise, a policy of de-Christianization was put in place . The end of monastic orders was decreed, churches were requisitioned to give place to the cult of the Supreme Being, the Christian calendar and religious festivals were abolished and replaced by republican festivals.

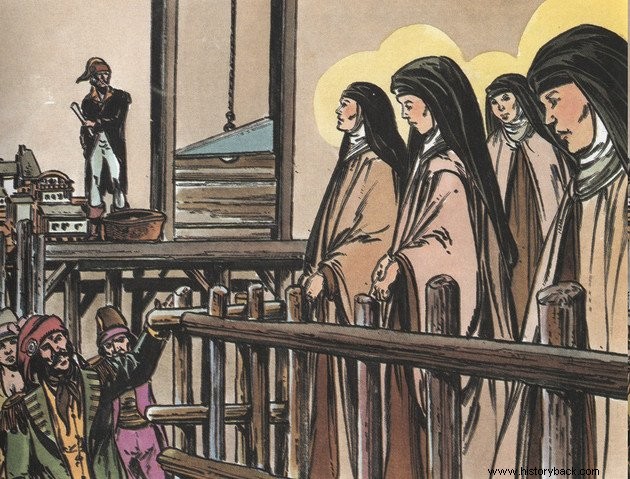

Those monks who did not leave the convents were condemned to death. The best known case was that of the Carmelites of Compiègne, when 16 nuns of the Order of Carmo were sentenced to death by guillotine in 1794.

Social, cultural and economic measures

During the Jacobin period, in addition to violence, laws were passed that ended up shaping modern France. Some examples are:

- Abolition of slavery in the colonies;

- Setting price limits for basic foodstuffs;

- Land confiscation;

- Assistance to the indigent;

- Replacement of the Gregorian calendar by the Republican;

- Creation of the Louvre Museum, the Polytechnic School and the Music Conservatory.

End of the Period of Terror

The Jacobin party succumbed to internal disputes and the radicals tried to intensify the executions in the courts in summary trials.

Ironically, representatives of the party wing at the end of the Terror were taken to the guillotine. On 9 Thermidor of 1794, the Marsh, a faction of the financial high bourgeoisie, stage a coup, seize power from the Jacobins and send popular leaders Robespierre (1758-1794) and Saint-Just (1767-1794) to the guillotine.

The disputes in France take place under the eyes of European leaders still fearful of political developments. Therefore, in 1798 the Second Anti-French Coalition was formed, which brought together Great Britain, Austria and Russia.

Fearing the invasion, the bourgeois resort to the Army, in the figure of General Napoleon Bonaparte and this, in 1799, triggers the Coup of the 18th of Brumaire. It was an attempt to restore internal order and military organization against the external threat.

Coup of the 18th of Brumaire:Bonaparte comes to power

The Coup of the 18th Brumaire of 1799 was planned by Abbé Sieyès (1748-1836) and Napoleon Bonaparte. Napoleon deposed the Directory using a column of grenadiers and established the Consulate regime in France. Thus, three consuls shared power:Bonaparte, Sieyès and Roger Ducos (1747-1816).

The trio coordinated the drafting of a new Constitution, promulgated a month later, which established Napoleon Bonaparte as First Consul for a ten-year term. The Magna Carta still granted him dictator powers.

Dictatorship was used to defend the French from external threat. French banks granted a series of loans to support wars and the maintenance of the achievements of the French Revolution.

So begins the political and military rise of France over the European continent.

See also:Napoleonic Era French Revolution - All MatterRead more :

- French Revolution

- The Fall of the Bastille in the French Revolution

- National Constituent Assembly in the French Revolution

- French Revolution (Abstract)