Potlatch on the northwest coast of the indigenous people

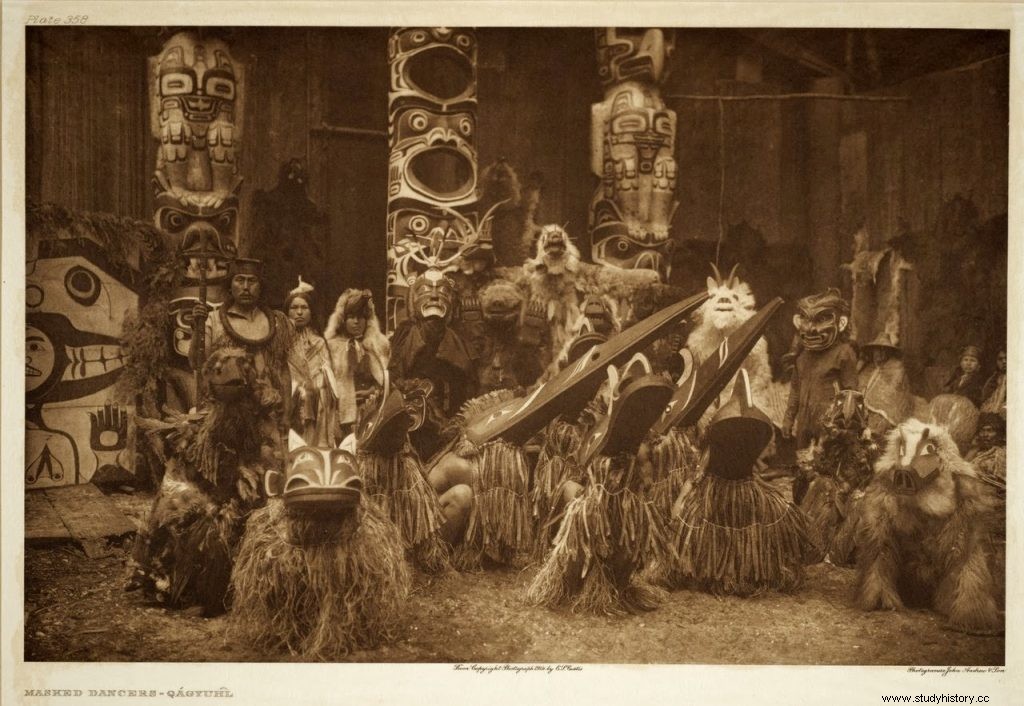

The potlatch, or banquet hall system, is an integral part of the governance structures of many indigenous cultures found along the northwest coast of the Pacific Ocean in North America. Decisions are made during this ceremony, which lasts for many days. The transfer of territorial rights and privileges over land ownership has been announced. Marriage is celebrated and the dead are mourned. The Kwakwaka'wakw people, whose traditional territory includes parts of Vancouver Island and mainland British Columbia, also use Potlatch to announce and keep track of their genealogy, as they have a complex system for tracing clan membership and lineage. They are a bilingual society, which means that they trace their ancestry through both mother and father. There are eighteen clans among Kwakwaka'wakw. Each family also has emblem art attached to it, and members who are not from a particular clan may not use certain artistic motifs belonging to that clan. The very word "Potlatch" comes from a trading jargon, Chinook, and means "to give." Large amounts of wealth are redistributed among the community during the Potlatch celebration ceremony. These include beautiful chilkat rugs made from mountain goat wool, food and artwork in the formline style, which is the signature art style associated with the Northwest Coast. The stories of the Kwakwaka'wakw people are passed on through song and dance, with re-enactments of the traditional stories involving dancers with masks.

One of the dances that takes place during Potlatch is known as Hamsamala, which takes place during the Hamatsa ceremony and involves dancers wearing bird masks from cedar wood. The Canadian government banned all indigenous ceremonies in Canada, including Potlatch, from 1885 to 1951. During this time, Potlatch was secretly continued even though some were closed and masks used in them were confiscated by authorities. The Kwakwaka'wakw people fought for their rights to continue the ceremonies and for the reproduction of bird masks. Today, they proudly continue the tradition of the Hamsamala dance, and Potlatch continues to be a central part of their culture.

The Hamatsa Ceremony and the Hamsamala Dance

The Hamatsa ceremony centers around an initiate, one who performs a transformation into a wild cannibal spirit, which other dancers will capture and tame. This initiate can spend time fasting in the wilderness and then return for the taming ceremony. He wears a cedar bird mask and is covered in shredded cedar to look like a plumage. The hinged beak on the mask can be opened and closed high using a fastened braided twine rope. This may give the impression that the bird is hungry and snaps its beak to eat. As the initiate undergoes capture and taming, he is adorned with elaborate regalia including buttonholes, bracelets, ankle braces and necklaces. A female relative of the Hamatsa inauguration prepares food for him during the taming. The taming is meant to be metaphorical, since it represents the socialization of a child or the cultivation of a young person to the Kwakwaka'wakw roads. In the Kwakwaka'wakw culture, cannibal lands are seen as childish and undisciplined. Both children and cannibals are hungry and must be taught how to behave in society. The Hamatsa ceremony reflects what it is like for a child to be initiated into the Kwakwaka'wakw community by taming the cannibal dancer. When taming is complete, the initiate returns to a calm, peaceful state and can live in the community.

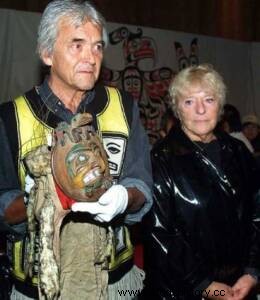

The Hamsamala dance is part of the Hamatsa ceremony. It involves many dancers wearing masks representing Hamsaml (cannibal birds). These bird masks are given many different names, such as the Gwaxgwakwalanuksiwe (raven at the northern end of the world) pictured below. This mask was created by an unknown Kwakwaka'wakw artist and belonged to Harry Mountain of Village Island, British Columbia before being confiscated from an illegal potlatch in 1921 under the Potlatch Ban in 1885-1951. It was later repatriated to the U'mista Cultural Center, established by the Kwakwaka'wakw people near Alert Bay, British Columbia, after fighting for the right to have ceremonial artifacts returned from museums and collections around the world. The mask is made of cedar, fabric and rope and is painted red and black. There is also evidence of repairs made to the mask with metal and nails. These birds are said to serve Baxwbakwalanuksiwe '(human eater at the northern end of the world) which is a cannibal with many mouths to which the birds must bring food. The right to perform the actual Hamsamala dance belongs only to some Kwakwaka'wakw families. This right is said to have been transferred to the family of Baxwbakwalanuksiwe 'himself. The bird masks perform transformation. The dancers who carry them go mad to behave like the cannibalistic spirit depicted in them.

The 'Namgis clan of Kwakwaka'wakw has a story about how they acquired the rights to perform Hamatsa. According to the story, four brothers found the house of the cannibal Baxwbakwalanuksiwe '. The cannibals chased them to try to eat them, but the brothers got away with magic tricks such as making a fog with the fur of a mountain goat. When the brothers returned home, they knew that the cannibal would still be after them. They set up a trap for Baxwbakwalanuksiwe ', which was a pit of hot stones and boiling water. The cannibal refused to return to his home at the northern end of the world and fell into the pit. After this, the brothers went to the cannibal's house and collected his bird masks. This will be the basis of the Hamatsa ceremony.

Formline Art Style in the Northwest Coast Indigenous

Art historians have noted that the formline art style found on the northwest coast has remained remarkably stable for hundreds of years. It can be found on totem poles, cedar houses, treasure chests used to give gifts under the Potlatch, and of course on transformation masks. Due to the stability of the art style, it is possible that these masks have been made in similar styles for over a thousand years. But since they are made from organic materials such as wood and feathers, it is difficult to know for sure how long the tradition of Potlatch and Hamatsa has lasted. Transformation masks such as the raven masks used during the Hamsamala dance are used to recreate the stories of Kwakwaka'wakw. The common elements of formline art include egg-shaped shapes, U-shapes and thick contours. The common colors of paint used are black, white and red. Ovoid shapes are particularly common in the eyes, which can be seen in the eagle mask below.

Making Hamatsa transformation masks can take months or even years and uses red cedar, which is a common material in northwestern art and architecture. The use of organic materials such as wood, rope and feathers means that these masks decay quickly. As a result, most of the surviving pieces are from the 19th or 20th century. Nevertheless, the artistic tradition in the Northwest has been relatively stable through the ages, and it is believed that these masks began to be made over a thousand years ago.

ThePotlatch Ban

The Indian Act of Canada, introduced in 1876, sought to control all aspects of the lives of indigenous peoples in Canada. The established reservation system, which forbade indigenous peoples to leave reserves without the permission of an Indian agent. Large gatherings of indigenous peoples were banned. Among the most devastating parts of Indian law was the establishment of residential schools, which thousands of indigenous children were forced to attend. Many suffered physical abuse and poor sanitation while attending these schools, and at least 3,200 were killed. Children in residential schools were forbidden to speak their language or practice their culture. The last residential school closed in 1996 in Punnichy, Saskatchewan. Residential schools threaten the survival of indigenous peoples' cultural traditions and languages. They continue to have long-lasting consequences and emotional trauma today on the families of those affected.

Indian law also forbade ceremonies such as Potlatch, as well as the use of traditional regalia. While indigenous cultures and their survival were threatened by the Canadian state, the Kwakwaka'wakw people were determined to continue to practice the Potlatch tradition in secret. An illegal Potlatch in 1921 became known for being shut down by the authorities and led to the confiscation of several Hamsamala dance masks. This became known as the Cranmer Potlatch. Cranmer Potlatch officers took such a risk as Potlatch is an integral part of the survival of West Coast cultures. Kwakwaka'wakw considers it an important part of their identity.

Cranmer Potlatch from 1921

Cranmer Potlatch was held on Village Island, British Columbia in 1921 during the Potlatch Ban from 1885 to 1951. It was one of the largest potlatches in history with over 300 participants. When regional magistrate William Halliday found out about Potlatch, he arrested 22 companions and demanded the surrender of all masks and regalia used in Potlatch. This included over 750 objects that ended up in various museums around the world. Through Halliday, some artifacts made their way to the Royal Ontario Museum. Thirty pieces were sold to George Heye, the founder of the Museum of the American Indian. Eleven were held by Duncan Campbell Scott, Superintendent of Indian Affairs in Canada, who was largely responsible for housing school policy. After the Potlatch ban was lifted in 1951, Kwakwaka'wakw fought to have the Potlatch masks and other objects repatriated to the U'mista Cultural Center near Alert Bay, British Columbia. The idea of museums is a colonial introduction. The Kwakwaka'wakw people did not have museums, as they considered the oldest and the stories they transmitted through oral tradition to be more important in preserving their history than displaying objects. This is why when the U'mista Cultural Center was built, the architectural style was carefully in the style of the Northwest Coast instead of Euro-Canadian architecture. The design of the cultural center is inspired by traditional cedar houses and treasure chests. Treasure chests are common in artistic traditions on the northwest coast and are usually covered with designs of family emblems. They can be used to inherit or inherit gifts in pots.

The Strength of Indigenous Traditions

Visitors to the U'mista Cultural Center can see the masks on display. When it's time for a Potlatch, the masks are taken off the screen and still used by the Kwakwaka'wakw people to continue the tradition of the Hamsamala dance and their other ceremonies. A large cedar tree house known as a large house is used to host potlatches in the Kwakwaka'wakw community near Alert Bay, British Columbia. Potlatch was forced underground and the Canadian state tried to punish anyone who participated in the tradition for over 60 years under the Potlatch ban. The Kwakwaka'wakw people fought for their rights and for their masks to be repatriated. Now they proudly carry on the traditions of their ancestors and are determined to maintain it for generations to come.