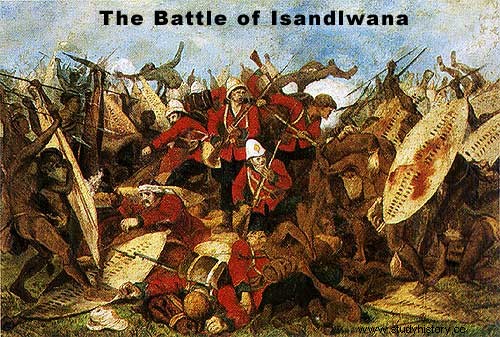

Isandlwana was one of the hardest blows to the forces of 19th century imperialism; the events that took place there reminded the colonial powers not to underestimate the capacities of the indigenous opposition. Initially intimidated by the firepower of the British, the Zulu warriors crushed the English line in a wild wave of hand-to-hand combat.

At the end of the 19th century, the way Westerners waged war seemed unrivalled. European empires dominated most of the globe from Africa to Asia, and even the United States populated by European settlers had become the dominant power after a succession of colonial wars. Artillery, rifles, machine guns and solid logistics were used by Europeans all over the world to subdue local resistance, which often had access only to outdated weaponry. Two battles in the 1870s, however, deeply shook this sense of confidence.

In June 1876, at the Battle of Little Bighorn, Lieutenant- Colonel George A. Custer and about two hundred officers and men of the 7th United States Cavalry Regiment were annihilated in an attack on a Sioux encampment. Custer had been advised to bring machine guns before he left, but he refused, confident in the superiority of his gun-toting men. But the Indians were also armed with guns and easily overwhelmed this ill-prepared American force. Three years later, an even greater disaster awaited British soldiers, the troops that had forged an empire, in South Africa where they faced native warriors armed only with spears.

NOTHING TO FEAR

The history of South Africa shows that the arrival of Europeans and the taking of territories by force had again only the identity of those who were responsible for the annexations; before the activities of the English and the Dutch, many local peoples had suffered a similar fate in the face of the Zulus, an aggressive people who had conquered the neighboring tribes and formed a powerful kingdom in the region. In the Transvaal, the Boer settlers disputed the possession of the lands with the Zulu king Cetshwayo. Initially, Britain supported the Zulu claims, but when the British Empire took control of the Transvaal, it was deemed wise to defend the rights of the settlers and prove that the British dominated the region by challenging the indigenous group more powerful. In December 1878, an ultimatum was presented to Cetshwayo, an ultimatum which the English knew he could not accept. The following month, an English army entered Zululand.

Lord Chelmsford, commander of British forces in South Africa, led some 5,000 English soldiers and 8,000 native auxiliaries into Zululand on January 11, 1879. His men were equipped with the latest weapons, and he had little reason to fear an enemy armed only with spears and old-fashioned guns. English Martini-Henry rifles could fire up to 12 rounds per minute, while machine guns, rockets and Gatling artillery were even more destructive. Cetshwayo had a larger army of 40,000 warriors, but to stand any chance against a modern army they would have to get as close to the English line of fire as quickly as possible.

Chelmsford's plan was to take Cetshwayo's capital, Ulundi, in a vast pincer movement, but to do this he split his army into three columns, diminishing his overall strength_ On 20 January Chelmsford encamped, with his central column , at Isandlwana, at the base of a distinctive-looking mountain called a nek, from its resemblance to a saddle. His scouts told him that Zulus were gathering nearby, and he decided to confront them before dawn two days later.

It was a fatal decision. Leaving half his men in camp - barely 1,700, including 700 infantry from the 24th Regiment - he went into battle with the other half. A much larger force of 20,000 Zulus was at the same time rounding the flank of Chelmsford and hiding in the rolling countryside about 8 km from Isandlwana.

Zulu ATTACK

.3 Zulus launched their attacks in a crescent formation, called "the horns of the beasts", within which flanking attacks would crush the enemy. As long as the enemy, in this case the British, held the perimeter of their position, they would be safe, as their gunfire and artillery fire had a terrifying effect on the Zulus.

.3 Zulus launched their attacks in a crescent formation, called "the horns of the beasts", within which flanking attacks would crush the enemy. As long as the enemy, in this case the British, held the perimeter of their position, they would be safe, as their gunfire and artillery fire had a terrifying effect on the Zulus.

An English gunner describes the effect of their high explosive shells on the Zulus, recalling that they "looked around wondering where the bullets were coming from, what they didn't understand, the shrapnel bursting at 45m of them and the bullets whizzing past their ears, it's no wonder they were surprised, for seeing a broadside fired into their midst and not knowing where it came from was enough to surprise the bravest .

The effect of the English rifles was no less intimidating, for while the Zulus had their own rifles, they were far less experienced and often aimed too high to hit their target.

At Isandlwana, the Zulus took shelter in the hollows at the edge of the flat grassland surrounding the mountain. They quickly learned that when the English gunners retreated behind their guns to fire, they had to lie down to avoid the shells. While hiding from the brunt of the gunfight, they made a dull noise like the buzzing of a swarm of angry bees.

Eventually, the local commanders of each centrally located Zulu group grew tired of seeing their warriors go to bed and taunted them, telling them to get up and fight. They began to advance slowly, but at a distance of about 120 meters from the English line, they gave their battle cry:“uSuthu! and charged.

The sight was terrifying. The panicked soldiers fell back towards the encampment, the Zulus catching up with them and breaking their formations. Confusion engulfed all involved, and Zulus soon surrounded each soldier, sometimes so numerous that not all of the warriors could reach their victim.

The soldiers fought blindly and bravely, striking all those who were within their reach.

A Zulu warrior, uMhoti of the uKhandempemvu tribe, noted the desperate nature of the fight:"I then attacked a soldier whose bayonet pierced my shield and as he tried to extract it I struck him in the the shoulder. He dropped his rifle, grabbed me around the neck and threw me to the ground under him. I felt like my eyes were popping, and I was nearly strangled when I managed to grab the spear still stuck in his shoulder and ram it into his vitals, and he rolled to the ground, lifeless. . My body was covered in sweat and shaking terribly from the suffocation inflicted on me by this brave man. »

Both sides inflicted heavy losses. Eventually, the overwhelming numbers of Zulus ensured victory, and the surviving Britons in the encampment attempted to flee down the path to the river behind Isandlwana. They were shot there by Zulus who had surrounded the mountain, cutting off their escape. None were spared, even though they begged. More than 1,200 white soldiers and their native allies were massacred, the Zulus losing at least 1,000 men, and many more seriously wounded.

Lord Chelmsford returned to his camp as night fell, but it was not until daybreak that the true horror of the defeat was revealed. The British Empire, at its peak in popular imagination, had been militarily humiliated. This rout was avenged at the end of the year with the defeat of the Zulus, but it was a taste of further difficult colonial struggles in South Africa.

FACING THE ZULUS

“The masses of gloomy men, in open order and displaying admirable discipline, followed each other in rapid succession, running with an even step through the tall grass. Having veered steadily so as to be exactly in front of our front, the greater portion of the Zulu divided into three lines, into small groups of five or ten men, and advanced towards us... A group of five or six rose and darted through the tall grass, dodging this way and that with bowed heads, guns and shields held low and out of sight. They suddenly disappeared into the grass, and only puffs of billowing smoke still indicated their location. »

Quoted in The Anatomy of the Zulu Army

by Ian Knight (Greenhill Books, 1995)