The work of the surveyors was not confined to the calculation and staking out of the roads. Thanks to the huge amounts of data they were able to collect (distances between cities, obstacles, bridges, etc.), they provided the basis for the work of the people responsible for drawing up the maps.

The working basis of Roman cartographers was the scroll, of standard length and width and completely filled. This implies a distortion of the overview, the scale does not exist as on our current road maps. However, the Roman traveler could find there many indications on the stages or the relays, the length of the stages, the obstacles or the remarkable places (capitals, sanctuaries), which mattered most to the traveler of this time.

The Antonine itinerary

Antonin’s itinerary is, for its part, an indicator booklet where all the routes are listed, the stages and the distances. It is inspired by the table of Peutinger and was first drafted during the reign of Caracalla (from which it takes its name, Antoninus being the people of Caracalla), then probably remodeled at the time of the Tetrarchy, in the end of the third century, because it evokes Constantinople. It was probably made from a wall map.

The Peutinger table

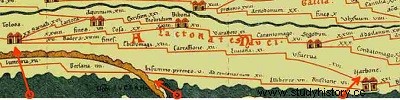

The best-known document that has come down to us is the Peutinger table, or Theodosian table. It is in fact the copy, made by an Alsatian monk in the 13th century, of the document produced at the beginning of the 3rd century by Castorius. This document could also be a copy of the map of the Empire of Agrippa intended for his father-in-law, the Emperor Augustus. Given to the humanist Konrad Peutinger, it is now in the library of Vienna, Austria. In 11 sheets (6.80 m by 0.34 m in total), the Table represents the known world of the time, from England to North Africa and from the Atlantic to India.

Other documents

In the 19th century, four goblets were found in Lake Bracciano, near Rome. Les Goblets de Vicarello (from the name of the place of discovery) bear, engraved on several columns, the names of the relays and the distances separating them, on the route that goes from Rome to Cadiz.

Other documents, more precisely centered on a route, existed. This is, for example, the case of the routes of the pilgrimage to Jerusalem such as those of Eusebius of Caesarea, Nicomedia or Theognis of Nicaea. They are later (4th century) but the system remains the same:the stages, the distances between these stages, the relays.