The Second World War gradually ended in Europe in the spring of 1945 (in the Pacific it lasted until the end of the summer). After Hitler's death on April 30, Admiral Dönitz replaced him as head of the German government and on May 2 he surrendered Berlin to the Soviets, the same day that most of the Wehrmacht laid down its arms. The definitive and unconditional surrender was on the 7th of that month, although some posthumous combats were still fought. The one that is considered last did not conclude until May 20 and had quite peculiar characteristics; It was what is known as the Georgian Revolt of Texel.

Texel is an island, the largest of the Frisian Archipelago, which belongs to the Netherlands and is located between Den Helder (connected every 15 minutes by ferry), Noorderhaaks and Vlieland. It has an area of 585.96 square kilometers (about twenty long by about 8 wide), a good part of which is water. In fact, it is actually two islands, Eierland and Texel proper, which were joined in 1630 by the construction of a dike that left the strait separating them a polder with its village and all:De Cocksdorpo (originally Nieuwdorp).

On August 31, 1940, this place was the scene of a naval battle between the Allies and the Germans. Or, to be exact, the sinking of two Royal Navy destroyers from a flotilla when they sighted what they took to be an invasion naval force - it wasn't - and, going out to intercept it, hit mines; a third destroyer that came to her aid was also damaged, although she managed to save herself. The Texel Disaster , as it was baptized, originated the rumor that the Germans had been repulsed by burning oil over the sea; nothing could be further from the truth because, as in the rest of Dutch territory, the swastika flag would fly there for the rest of the conflict.

The destroyer incident cost 300 lives and a hundred prisoners but that island was going to collect an even greater tribute, with the tragic irony that it would do so with the war already over. As we said before, it all started at midnight on April 5, 1945, while the 1st and 9th armies of the American general Omar Bradley completed the encirclement of the Ruhr area, capturing nearly 300,000 German soldiers, before turning east to establish contact with the Red Army on the Elbe, which they would achieve in the middle of the month.

It was about one in the morning when Georgian members of the 882nd Battalion Königin Tamara , a unit named after a 12th-century Georgian queen and made up of captured ex-Soviet fighters offered to enlist in the German ranks and destined precisely for Texel, staged an unexpected insurrection that gave them control of almost the entire island, hoping to be helped by Allied paratroopers whose arrival was rumored to be imminent, given the course of the war and that the Dutch resistance had requested.

Those Georgians who had fallen prisoner on the Russian front had to face a serious choice:be interned in concentration camps or accept the offer to go over to the opposite side as auxiliary troops along with their fellow volunteers. There were already a few Wehrmacht units made up of foreigners, many of them openly anti-communist in character, and the Georgian Legion, of which the unit was a part, therefore received preferential treatment; after all, the Georgians were considered Aryans (some were even advisers to Alfred Rosenberg, such as Alexander Nicuradse or Michael Achmeteli) and were counting on them to control a hypothetical Georgia independent of the Soviet Union.

Considering that agreeing to go to a camp was almost certainly equivalent to death, most chose to wear the German uniform; despite Hitler, by the way, who did not quite trust them because they only had a small percentage of Nordic blood. However, the Wehrmacht failed to occupy Georgia and the Legion would operate mostly in the Ukraine. Of course, there were exceptions because thirteen battalions of five companies each were formed and some, as a result of the aforementioned suspicion of the Führer, would go to the other end of Europe to fight on the Western Front.

In June 1943, having gathered a considerable number of men, they were sent to Kruszyna, a town in Mazovia (central-eastern region of Poland), not far from the industrial city of Radom, to form the battalion. The number of troops amounted to 800 Georgian soldiers plus 400 Germans, the majority of the latter being officers and non-commissioned officers. As usual, this force was used above all in the anti-guerrilla struggle; At least initially, since in August he was ordered to relieve the Indische Freiwilligen Legion (a Waffen SS regiment made up of volunteers and Indian prisoners of war), stationed in Zealand as part of the Atlantic Wall.

The 1st Indian Battalion had been stationed at Zandvoort since May and the 2nd at Texel. The Georgians arrived at the first location on August 30 and garrisoned there until February 1945, while deciding whether to rename their unit to IV. Battalion Jäger-Regiment 32 and integrate it into the 16th Luftwaffe Field Division. In the end, it kept the original name and on the 6th they were transferred to the island, given that the threat of an Allied invasion loomed over the country. That rumor was, paradoxically, the one that incited the Georgians to rebel; after all, they had nothing to lose.

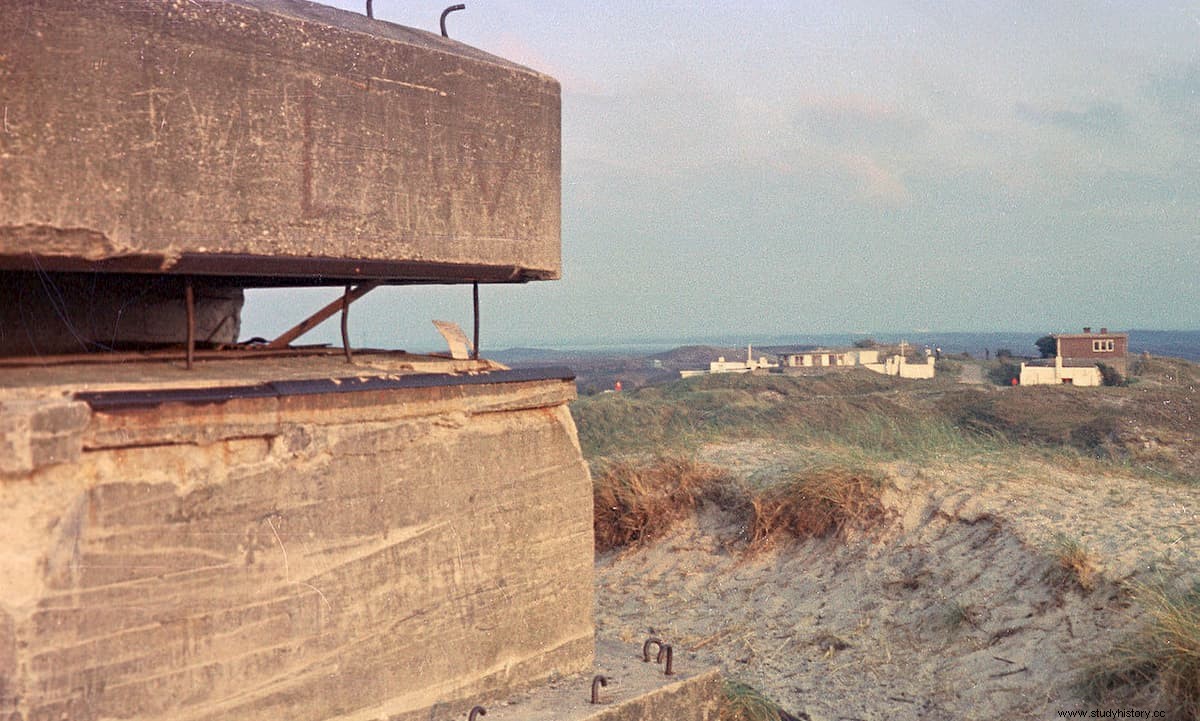

On the aforementioned night of April 5, by agreement, the Georgians got rid of the German officers while they slept and gained control of most of the island. Only the coastal batteries on the north and south coasts managed to resist, which served as a bridgehead for the reinforcements that quickly arrived from the mainland:2,000 men of the 163rd Marine-Schützenregiment (surplus sailors converted into infantrymen) who, with artillery support, in just a couple of weeks recovered the insular domain defeating the rebels, while they waited in vain for Allied help; They had only obtained that of the Dutch resistance and that of some local residents, who paid a high price of more than a hundred dead.

As the deceased Germans were about 400, to which many others had to be added in the subsequent combats (the number is uncertain and there are sources that increase it to two thousand), and the Georgians also suffered an ostensible number of casualties, 565 (between them their leader, Shalva Loladze), it is clear that those combats were agonizing and stark. But, of course, without outside help, only the end it had could be expected. German Marines swept the grounds from house to house, rounding up most of the Georgians, whom they deemed traitors and summarily shot after being forced to dig their own graves and strip off their uniforms.

228 surviving Georgians tried to hide as best they could, some hidden by the local population and others, desperately, in minefields or haystacks. The tragic irony was that a month later Germany would surrender, but at Texel hostilities continued because the German commander (who had escaped by spending the night on the mainland with his lover) regarded his opponents as nothing more than mere traitors and therefore This disregarded the instructions to that effect sent by Lieutenant General Guy Simonds, of the II Canadian Corps, which had occupied Holland. This was the case until May 20, when those troops, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Kirk, had to land there and put an end to what was the last battle of World War II on European soil. The nightmare seemed to have ended happily; however, a sinister epilogue was missing.

Despite Canadian intercession, the provisions of the Yalta Conference required the repatriation of all Soviets held by the Axis powers, so the Georgians were sent to the Soviet Union. There, although the daily Pravda praised them as patriots at first, they discovered that later they were not treated as heroes but accused of treason, for having agreed to join the Wehrmacht. The attempt by four of them to escape by boat to England to pledge allegiance to the Allies had been unsuccessful. Their last revolt served to avoid trial but not for part of the main group to end up in gulags, since Stalin had considered anyone who allowed himself to be captured by the enemy deserving of punishment.

As of 1956, with the destanilization, those who were still alive began to be released. It is curious that, then yes, they were recognized the merit denied before. The Soviet ambassador to the Netherlands visited the Hogeberg cemetery in Texel every year (until the fall of the communist regime in 1991), where most of the fallen were buried; in 2005 it was the president of Georgia, Mikheil Saakashvili, who stopped by to honor them with a ceremony in which he spread Georgian earth on the graves. For their part, the mortal remains of the fallen Germans rest in the Ysselsteyn military cemetery (Limburg), where they were transferred in 1949 from Den Burg, the island capital, at whose airport there is an Aviation Museum that includes a permanent exhibition about these facts.