It is almost impossible that someone has never seen a movie about the Pacific campaign in World War II. So, it is also unlikely that the word banzai is unknown; who more who less, we all know that the Japanese soldiers shouted it in battle. Actually, it is the synthesis of a longer expression, as we will see. We are interested here because, in a certain context, it gave a name to a desperate action that was carried out when everything seemed lost:the Banzai charge .

The full expression is ¡Tennōheika Banzai! , which was emphatically uttered and can be translated as Long live the emperor! . However, this translation is rather an adaptation, since it literally means Ten thousand years , as its original version reads, wànsuì . If someone speaks Japanese or Chinese, they will have noticed that wànsuì It is not a Japanese term. It arose in ancient China without knowing exactly how, although a legend explains it with the characteristic fantastic tone. There is always a legend.

That legendary story says that, miraculously, the Songshan (a mountain in the province of Henan that was considered sacred, which is why Buddhist temples and monasteries abound on its slopes, including the famous Shaolin) told Emperor Wu of Han. when he visited him in 110 B.C. Since then, it has been associated with the throne as a way of wishing its holder a long reign, although during the period of the Five Dynasties and the Ten Kingdoms its use was extended to all members of the imperial court; ephemerally, because later it returned to be exclusive to the ruler.

This did not prevent powerful eunuchs such as Liu Jin or Wei Zhongxian from devising a daring alternative that brought them closer without equaling them, avoiding falling into contempt:using jiǔ qiān suì , which means nine thousand years . The most frequent complete sentence was, repeated several times, «Wú huáng wànsuì, wànsuì, wànwànsuì "(May my Emperor [live and rule for] ten thousand years, ten thousand years, ten thousand [times] ten thousand years ). The empresses had to settle for only a thousand, except for the powerful Cixi, who ruled between 1861 and 1908 (in her time the Boxer Rebellion and the siege of Western embassies broke out) and was granted the wànsuì , as some photographs of the time show.

In an analogous way to one hundred thousand, which the Spanish chroniclers of the 16th and 17th centuries used in their writings to refer to an enormous number of enemies or inhabitants, for the Chinese the number ten thousand had a symbolic connotation of infinity or incomprehensible and, therefore, In fact, the number one hundred thousand is expressed as ten tens of thousands. That is why the translation that is usually done today is the aforementioned Long life . Versions were even adopted in the 20th century, both during the Revolution and in the fight against the Japanese and in honor of the Communist Party or its leader; it was abolished in 2018, although it is still in use in North Korea and Vietnam.

And it is that China exerted a considerable political and cultural influence on the countries around it for centuries:thought, writing, religion... Hence, the expression crossed borders and took root in them, as we see. It arrived in Japan in the 8th century AD. or maybe earlier, since the Nihon Shoki (also known as Nihongi), the second oldest book on Japanese history, contains an account of an episode in Empress Kōgyoku's rule in which peasants shouted "Banzei!" at her. in 642 AD

As you can see, at first the word used was banzei , since the e didn't happen to be an a until the times of the Meiji Revolution. It was in this context that the constitution, enacted in 1889, incorporated the banzai as a ritual form in its first article and the university students acclaimed the young emperor as he passed in his carriage, thus recovering a tradition that had fallen into disuse for the leaders, although it was preserved in other areas (the members of the Jiyū Minken Undo or Jiyūtō , People's Rights and Freedom Movement that had supported the revolution, used to shout "Jiyū banzai !", i.e. "Long live freedom!").

Of course, the expression banzai It is linked above all with World War II, when the soldiers of the Japanese army exclaimed it when carrying out the charges they carried out when they saw defeat imminent. In fact, some scholars of the subject consider that the scream was part of the gyokusai , term translatable as jade fragments or, more loosely, broken jewel; it was used metaphorically to refer to an act of self-destruction, an honorable death. A concept also of Chinese origin, as reflected in a quote from the Book of Northern Qi (an official history of the homonymous dynasty completed by Li Baiyao in AD 636):A true man [would rather] be a broken jewel than be ashamed to be an intact tile.

That text alluded to the act of honor of hundreds of followers of the imperial clan, who died defending it against their enemies. Japan developed a similar ideal that made seppuku official, the famous ceremony that in the West is better known by the name of harakiri (a name that, however, the Japanese consider vulgar). It was part of the Bushidō (Way of the warrior), an ethical code that the samurai followed and that, with some tweaks to update it, was recovered after the Meiji Revolution as a way to break with feudalism.

The Bushido it was implanted in the imperial armed forces and in the administration itself. The fact that some illustrious character died heroically, following those precepts, gave him the romantic aura he needed for his acceptance. This was the case of Saigō Takamori, a politician and soldier who died desperately fighting the enemy during the Satsuma Rebellion of 1877 (or by seppuku, it is not entirely clear), while his last companions threw themselves sword in hand against the riflemen. enemies to die.

Something similar was done by the soldiers who charged the bayonet against the defenses of Port Arthur, dying under the Russian machine guns. The custom had already settled and although the losses were tremendous, in the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945) those attacks in waves were successful thanks to the fact that Chinese weapons were not automatic. That created a somewhat misleading impression, in the sense that they were adopted as a tactic. They received the name of Banzai loads , because the usual thing was to shout three times «¡Tennōheika Banzai! » raising arms over head.

Then, rather than be taken prisoner or surrender, they would run into the enemy while continuing to yell at him - often summed up as "Banzai!" only - with the aim of frightening him. At this point in the fight, the same weapon was used as the rifle as the bayonet, a katana or even a hand grenade to make it explode at the last moment. Of course it wasn't always like that. It was, after all, a desperate measure and that is why we had to wait until the halfway point of the Second World War for them to become widespread.

Some Banzai charges were shocking. For example, the two that were carried out on August 17, 1942 in the Makin Atoll (now Butaritari, Kiribati) against the US Marines, who landed in an operation that was part of the Guadalcanal campaign, which began ten days earlier:hundreds and half of Japanese, which meant the total of the garrison. That of Tenaru (island of Guadalcanal), four days later, was worse because eight hundred fell, with the same result; his boss, Colonel Kiyonao Ichiki, seppuku .

Another colonel, Yasuyo Yamasaki, led 2,600 soldiers in a new Banzai charge during the Battle of Attu (Aleutian Archipelago), running down the slope; they managed to overcome the defensive line and in the paroxysm they killed the patients of a hospital, but in the end only twenty-nine were left alive. However, the greater Banzai load , in which even civilians armed with bamboo spears participated because the propaganda had told them that the enemy would kill them anyway, took place in another latitude:in the Mariana Islands, where the Battle of Saipan was fought.

Lieutenant General Yoshitsugu Saitō was aware that the fall of that position would provide the United States with a magnificent base for its bombers to raid Japanese cities, so he was prepared to fight to the death. Said and done, on July 9, having resisted to the limit and defeat imminent, Saitō led his troops, leading a charge. Those four thousand three hundred men, some wounded who barely had the strength to run, were swept away by a barrage of fire. Of course, a Hispanic soldier managed to convince a thousand Japanese to surrender.

One of the toughest battles of the Pacific campaign was that of Iwo Jima. This small island of the Ogaswara archipelago had for its defense a network of underground tunnels that allowed the Japanese to open fire and change position quickly, making it difficult to conquer the rugged terrain. General Tadamichi Kuribayashi forbade his soldiers to make Banzai Charges for considering them useless; he preferred that it was the enemy who had to launch an attack against his well-guarded positions. Only at the end, when all was lost, he charged at the head of the two hundred men he had left after being crushed by the artillery, coming to a melee with the marines; All the Japanese died.

Of course, there were more Banzai charges , despite the fact that they had proved useless against well-trained adversaries with automatic weapons. However, the Japanese government insisted on them because it was willing to do anything to avoid an invasion of its territory; he expressed it this way at the end of 1944 with the promulgation of the ichioku gyokusai , whose meaning is one hundred million jade fragments , allusive to the one hundred million inhabitants that the country had. The number of American casualties that the putting into practice of this popular resistance would cause was one of the arguments used to approve the launches on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

In this context the tokkōtai were also born. or Shinpū tokubetsu kōgeki tai (Special Attack Unit Shinpū ), better known in the West as kamikazes; As is known, they were the pilots of the imperial air force who crashed their planes against enemy ships and who, like their terrestrial counterparts, obtained more media coverage than practical effects. The romantic view says that the kamikazes shouted "Banzai!" before hitting your target; It is something that has not been demonstrated for obvious reasons, although it is within the possible.

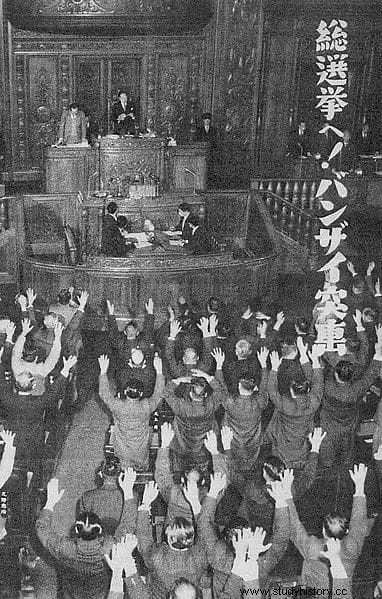

The expression has managed to survive over time, in part because the US troops that occupied Japan popularized it in the West. But today it is used as a victory cry, equivalent to hooray! , usually in a less violent context, sports. However, it continues to be exclaimed in the old way (repeating ¡Tennōheika three times Banzai! while raising arms) at certain official moments, such as the enthronement of a new emperor or when the Shūgiin is dissolved (House of Representatives) of the Kokkai (National Diet or parliament).