Some time ago we dedicated an article to the unprecedented case of Vesna Vulović, a Serbian stewardess who became famous in 1972 and is registered in the Guinness Book for having survived the fall of her plane from 10,000 meters. But this is not a unique case; several more are known, one of them just a year earlier, that of the German teenager Juliane Koepcke, who came out alive from an accident in the Peruvian Amazon despite falling from 3,000 meters. When most happened, however, it was during World War II.

One of the most interesting aspects of wars is the anecdotal. And, obviously, the more recent and prolonged, the better documented they are and the greater number of curious stories we know about them. That's why entire books have been published on World War II dedicated to that specific topic, and why we're also going to get into it by taking a look at the rare cases of aviators who managed to survive unbelievable accidents. There are quite a few, due to the numerous missions that were carried out and the frequency of shootdowns.

In all of them there were common factors that explain the miraculous salvation of their protagonists, such as the trees that cushioned the bodies when they fell or a thick layer of snow at the end, always softer than the ground (an article by Catherine Berridge explains it from the point of view of from the point of view of Physics). But, above all, it was luck that was the differentiating element, since other members of the crews often lost their lives. The case of the Handley Page Halifax, of the RAAF (Royal Australian Air Force), which exploded in the air when it was flying at 1,350 meters over the snowy Ruhr basin in 1944 and from which two of its men survived with a single parachute (Australian Lieutenant Joe Herman and Flight Officer John Vivash), may seem exceptional. But there were more, the following being the most famous.

Nicholas Stephen Alkemade

One of the most famous cases had an Avro 683 Lancaster as its starting point. It was a type of four-engined heavy bomber that entered service in 1942 and, due to its characteristics, was used for night missions at low altitudes, accrediting some 156,000 missions until the end of the war. That is why it is not surprising that his resume includes a second episode of amazing fall survival:that of Sergeant Nicholas Stephen Alkemade, who lived through his impressive experience only a month before the two colleagues mentioned above.

He was born in 1922 in the English town of Loughborough (Leciestershire, East Midlands) and served as a tail gunner in a Lancaster of the RAF's 115 Squadron. On the night of March 14, 1944, that plane, named S for Sugar (when translated it changes; it would be something like A de Azúcar ), was returning from one of the raids that three hundred aircraft had carried out over Berlin when, passing through Schmallenberg (in North Rhine-Westphalia), he was attacked by a Junkers JU 88, a type of aircraft whose versatility allowed it to be used in various functions; in sight of the enemy, he assumed that of hunting.

The Lancaster was engulfed in flames and lost control. The crew jumped by parachute, but when Alkemade was about to abandon the device, his caught fire and was rendered useless, so in a matter of seconds he had to face a terrible choice:perish on fire or do it faster by jumping, since they were at 5,500 meters of altitude. Feeling how the tongues of fire began to singe his clothes and skin, he chose the second option... and he was right because, as we said before, the flexible crowns of the fir trees and half a meter of snow saved him.

Some injuries, bruises and burns plus a dislocated right knee were all the damage suffered, while his four crewmates crashed with the plane and lost their lives charred. He even had the cold blood to light a cigarette, whose puffs he alternated with the blasts of a whistle so that they could locate him. As the lucky survivor was in German territory, he was picked up and handed over to the Gestapo, considered a spy. But, after interrogating him and finding the remains of the Lancaster that gave truth to his unheard-of story, he not only became a simple prisoner of war (he was interned in the Dulag Luft, a concentration camp in Frankfurt), but was granted a document that certified his odyssey.

Repatriated in May 1945, at the end of the war he worked in the chemical industry (where he emerged unharmed from two accidents that at first everyone believed fatal) and later participated in some television programs dedicated to remembering protagonists of war episodes related to audacity or survival under special conditions. He died in 1987, a year after another aviator who lived an odyssey similar to his did:Lieutenant Chisov.

Ivan Mikhailovich Chisov

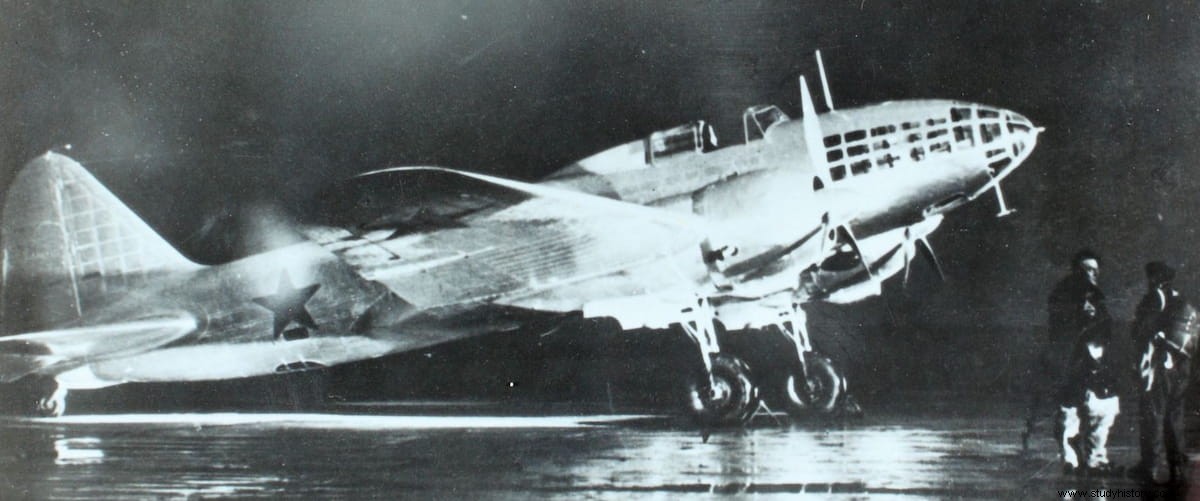

Ivan Mikhailovich Chisov was born in Bogdanovka, Ukraine, where he was born in 1916. During the Great Patriotic War (the name given in the Soviet Union to the confrontation with Nazi Germany on what is known in the West as the Eastern Front), he was assigned to the Voyenno-Vozdushnye Sily (Soviet Air Force) and assigned to an Ilyushin Il-4, a medium-sized but long-range bomber of which 5,256 units were manufactured. He was flying with it in January 1942 when it was attacked and hit by several Messerschmidtt Bf 109s, the model that formed the backbone of the Luftwaffe fighter force. .

Chisov put on his parachute and jumped. It is not clear how many meters he was from the ground; his companion, Nikolai Zhugan, who tried to save the ship without success, abandoning it at the last moment, when it was barely 500 meters high, said that Chisov was launched from approximately 7,000 meters. In any case, he did not immediately open his parachute because in the midst of an air battle he would have been an easy target for the German pilots, so he decided to wait until the battle level was exceeded. But he had no other factor.

And it is that the worst thing imaginable happened to him in those circumstances:due to the lack of oxygen he lost consciousness, so he continued to fall inert without being able to open the parachute. At a hair-raising speed of between 190 and 240 kilometers per hour, it crashed into the edge of a snowy ravine and rolled down it until the snow itself stopped it. It didn't take long for cavalry troops operating in the area to appear and were watching the aerial battle, only they thought they were going to pick up a derelict corpse, and to their amazement, instead they found a comrade alive and conscious.

Battered, yes; with significant damage to the spine and fractured pelvis. In fact, he was in critical condition and spent the next three months in a hospital, undergoing surgeries that ultimately saved him. Chisov was a veteran who had accumulated more than 70 missions, so he was not daunted and requested that he be redeployed to combat missions, but his condition did not advise it and in the end he was assigned the task of flight instructor. At the end of the war he graduated from the Military Academy and went into the reserves, dedicating himself to propaganda tasks.

Alan Eugene Magee

And so we come to the last known case of that kind. We already had British and a Soviet, so it is the turn of an American:Alan Eugene Magee, who went through the same thing as the previous ones just a year after Chisov, in January 1943. He was the worst off, with very serious injuries , because he found no snow to break his fall; Despite this, ironically, he would be the longest, living 84 years.

He was born in 1919 in a town, Plainfield (New Jersey), which in 1957 would become famous for something less edifying:the adventures of Ed Gein, the murderer who inspired the writer Robert Bloch and later the filmmaker Alfred Hitchcock for the character of Psycho , Norman Bates; Its inhabitants would surely have preferred that the name of their city be remembered for the adventure of the aviator. In December 1941, as soon as news of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, bringing the US into the war, Magee rushed to enlist.

He was assigned to what between 1941 and 1947 was called the USAAF (United States Army Air Forces ), United States Army Air Forces, joining the crew of a B-17 as a gunner. This one, nicknamed Flying Fortress (Flying Fortress), was a type of heavy bomber, manufactured by Boeing since 1935, which was used both in Europe and in the Pacific, delivering a total of 12,677 devices (part of them to the RAF). Magee served on the lower turret machine gun.

On January 3, 1943, the Snap! Crackle! Pop! (name that his crew had given the plane in reference to the funny drawing that decorated the fuselage:three elves, mascots of the Krispies cereals , riding on a bomb) was fulfilling his seventh mission as part of the 360º Bombardment Squadron, which attacked the French city of Saint-Nazaire in broad daylight, where there was an important German naval base. He was in it when an antiaircraft destroyed his right wing, causing the pilot to lose control of the device and it would fall spinning on itself. Magee was injured but was able to leave the turret and prepared to abandon ship.

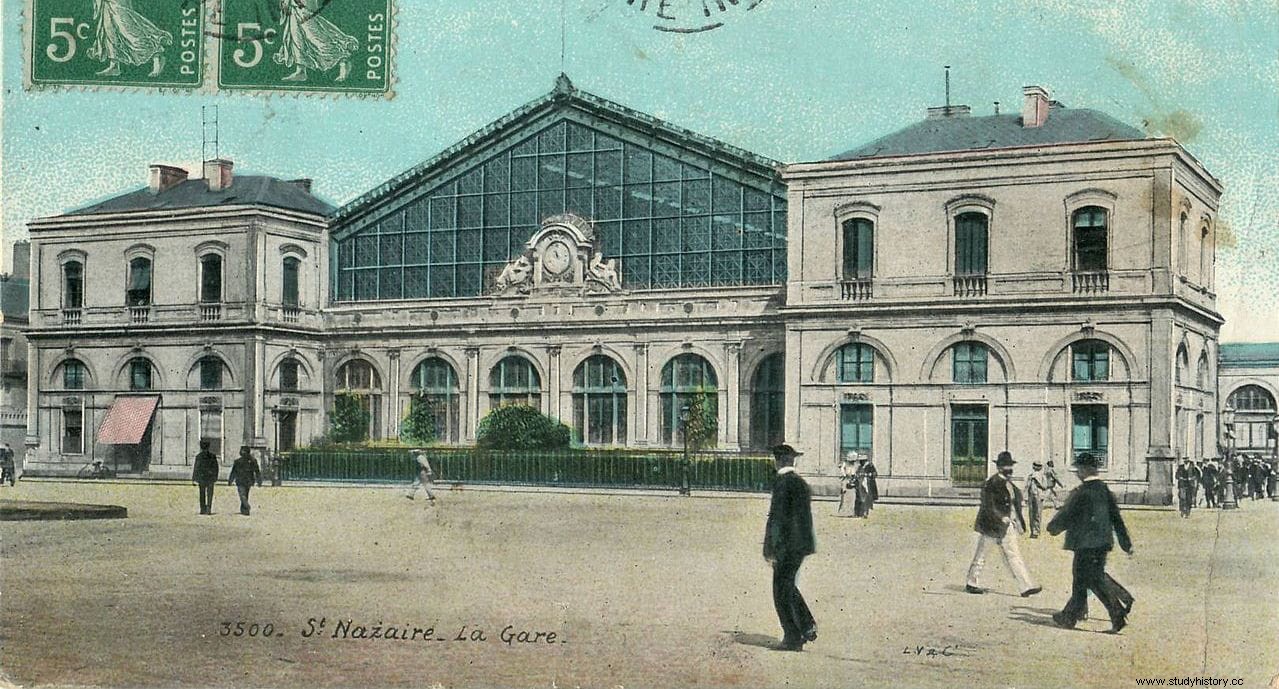

He then discovered to his horror that his parachute had been hit by shrapnel, rendering him useless. His choice was tremendous:stay on board and crash, or jump anyway. Magee opted for the latter and the same thing happened to him as Chisov, losing consciousness due to insufficient oxygen; in his case he would be welcome because he would die without knowing it. But no, he didn't die. Despite falling from 6,700 meters of altitude, he lived to tell about it because at the end of the journey there was no snow but the glass roof of the Gare Saint-Nazaire , the railway station.

The current terminal, of contemporary architecture inaugurated in 1995, has nothing to do with the one of the time, which was nineteenth-century and was practically destroyed by the bombings as it was located next to the submarine docks. As can be seen in the attached image, it consisted of two lateral stone bodies connected by a central one with a long glass roof, typical of the time it was built. It was that material, hard but brittle, that attenuated the impact force of the aviator's body, causing him to fall to the platform floor less violently. Of course, the crash was terrible anyway, and took its toll on Magee's physical integrity.

The Germans immediately understood what had happened, picking him up and taking him to a hospital. He had many broken bones, punctured lungs and kidneys, severe damage to his nasal septum and eyes, as well as a semi-amputated arm. That, only as a result of his fall, because he also had to add 28 shrapnel wounds. Despite everything, the doctors were able to get him through and the long convalescence served to make his new status as a prisoner of war more bearable.

He regained his freedom in May 1945, being decorated with the Air Medal (created in 1942 to reward aviators who had distinguished themselves for their merits or heroism) and the Purple Heart (the oldest decoration in the USA, given in the name of the President wounded or killed in combat). Many medals were awarded during those days, because in that mission 75 men lost their lives when 7 planes were shot down and another 48 were hit, who barely returned.

Like Chisov, Magee was not afraid to continue flying and at the end of the war he obtained a pilot's license, working in the aviation sector until his retirement in 1979. In 1993, Saint-Nazaire commemorated the 50th anniversary of that bombing by including among the acts the unveiling of a memorial honoring Magee and his B-17 comrades. The man who eluded the Grim Reaper in 1943 reconciled with her in 2003, through a combination of kidney failure and stroke.