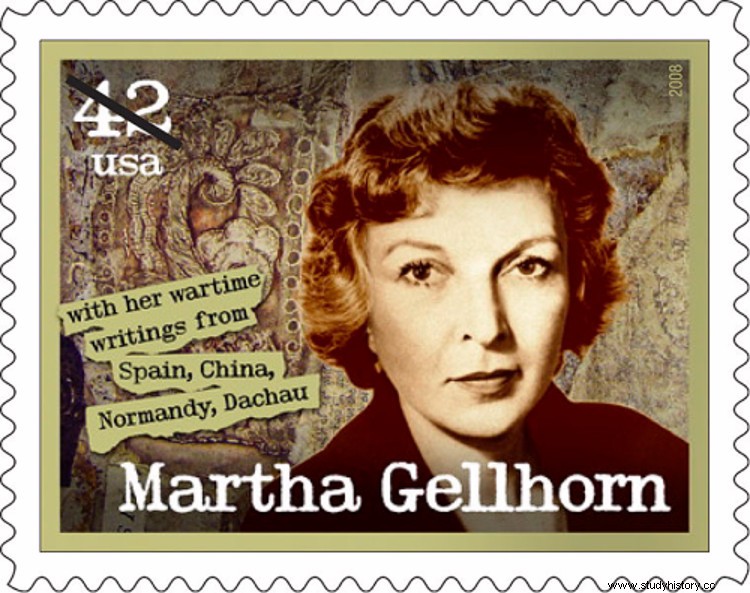

Probably many readers will know who Martha Ellis Gellhorn was but, for those who don't, tell them that she is not one of those characters that sometimes get shoehorned into war movies. She was the only woman known to have landed in Normandy on D-Day covering World War II as a reporter, just as she had done before with the Spanish Civil War and would later do with others. However, the merits of that eventful adventurous life are often relegated to the background when she is presented simply as the wife of Ernest Hemingway.

To be exact, she was the third of the famous writer, whom she met at Christmas 1936 in Key West. Hemingway spent winters there since 1928, when he was looking for a place to recover from a domestic accident suffered in Paris and another illustrious writer, John Dos Passos, recommended it to him. By then he was already a successful author, with works like In our time , Party , A farewell to arms or The snows of Kilimanjaro , for example, and I was working on To have and not to have .

He was also married to a Vogue journalist at the time. named Pauline Pfeiffer, for which in 1927 he had divorced his first wife, Hadley Richardson. And Martha appeared, who dazzled him with her self-confidence and independence, probably also because she was the first to be younger than him. Born in San Luis in 1908, her father was a gynecologist of German origin who, together with her mother, Edna, gave her two brothers, Walter and Alfred, both prestigious university professors although in different disciplines (Law and Medicine, respectively)

And that Edna was none other than, Edna Fischel Gellhorn, a famous suffragette who was involved in founding the National League of Women Voters and she defended tooth and nail the recognition of the female vote. She was the one who marked her daughter's character because she had already involved her since she was little in the fight for women's rights. Thus, in the photographs of The Golden Lane , a Democratic convention held in the city in 1916 in which some women appeared adorned with golden umbrellas to symbolize the states where they could vote and others did so with black accessories for which they could not, two girls are seen who represented the voters of the future; one of them was Martha.

In 1927 he began working as a journalist at The New Republic , despite not having the corresponding university degree. However, his articles must have been liked enough to continue for three years, until he decided to go to Europe to be a correspondent. He settled in Paris until 1932 at the service of the United Press agency and Vogue (as Pauline Pfeiffer), alternating that occupation with participation in the peace movement, which he would capture two years later in his first book, What mad pursuit .

Concluding that stage in the old continent, he returned to the US with an offer from Harry Hopkins, an adviser to Roosevelt -both were friends of Eleanor- who at that time was immersed in the application of the New Deal, the interventionist policy of the federal government to face the terrible effects caused by the Great Depression that followed the Crisis of 29. One of the entities in charge of implementing the different programs was the FERA (Federal Emergency Relief Administration), which focused on the creation of unskilled employment as alternative to subsidies.

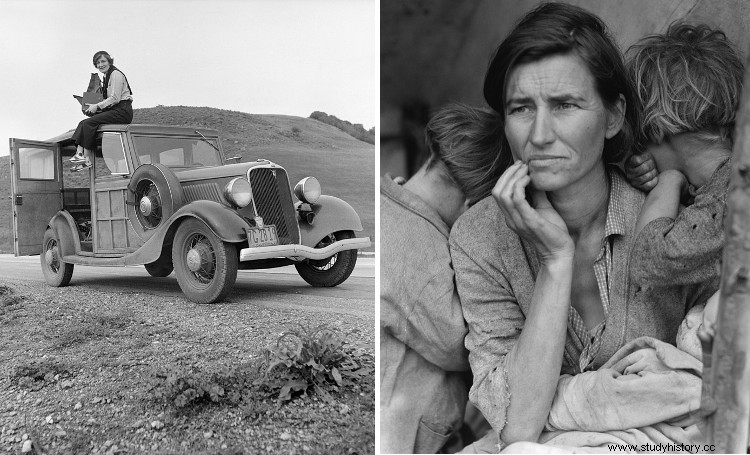

Martha served as an inspector for FERA, collecting data on the situation of people in need in North Carolina. She later broadened her field of research in collaboration with photographer Dorothea Lange. The result of that mutual cooperation was a series of written and graphic reports (the photo Migrant mother became especially iconic ) that today are very useful for studying the period but, in the case of the first, it also served as the basis for documenting a new book, The trouble I’seen , published in 1936.

That was the year she met Hemingway in Florida. They struck up a friendship and the writer separated from Pauline to settle down with Martha at Finca Vigía, a 61,000-square-meter hacienda located twenty kilometers from Havana. But they agreed to go to Spain, where a military coup led to a civil war. He traveled as a correspondent for the NANA (North American Newspaper Alliance ) and was accompanied by the Dutch filmmaker Joris Ivens, who was filming the film Tierra de España and he wanted the celebrated writer's help on the script. Martha did it hired by Collier’s Weekly magazine. , a pioneer in investigative journalism and with an editorial line that defends social reforms.

In Spain they consolidated their relationship living on horseback between Madrid and Barcelona. After celebrating Christmas together in 1937, Hemingway wrote The Fifth Column (her only play of hers) and she went to Czechoslovakia to follow the news of the thriving German Nazi regime. As a testimony of that stage, she would publish her first novel in 1940, A stricken field , already finished the Spanish war and untied the world-wide one. Of course, Martha did not return to her country, but she moved through the places where the conflict was hottest, from Finland to Singapore, passing through Hong Kong, Burma and Great Britain.

On November 20, 1940, she and Hemingway took the final step by marrying (Pauline's divorce had been finalized the year before). They did it in Cheyenne, Wyoming, establishing their domicile in Sun Valley, Idaho, although in winter they escaped to their house in Cuba, which they shared with dozens of cats. That fall Hemingway published For Whom the Bell Tolls , a novel set in the Spanish war that he wrote at the request of Martha and with which he won the Pulitzer Prize, rising in the literary world.

That professional triumph was not reflected in his staff. The marriage was a failure almost from the beginning because the writer did not take his wife's absences well at all. In January 1941 Collier's Weekly he sent her to China and he accompanied her but he was sulking all the time, since she didn't like the country. The imminent entry of the United States into the world war made them return but later, when Martha traveled to Italy in 1943 to cover the Allied advance, he reproached her for this new move by asking her in a letter if she was a war correspondent or his wife.

However, the worst was yet to come. Knowing that the Allies were preparing Operation Overlord, a large landing on the French coast that would open a new front, she decided to go to England with the idea of reporting from the front line, finding that her husband, who was already in London, did not He only did not help her but did everything he could to prevent her, refusing to arrange a press accreditation and the corresponding ticket to cross the Atlantic by plane.

It should be noted that in the British capital he had met another journalist, Mary Welsh, from Time magazine. , with whom he had an affair. In that sense, the betrayal was reciprocal, since Martha also had a love affair with a military man, James M. Gavin, commanding general of the 82nd Airborne Division. In fact, the journalist had also had dalliances in her youth, when she was in Paris, with the French economist Bertrand de Jouvenel, who was about to leave her wife for her.

Martha didn't back down; she was determined to go wherever the war was, as she put it in her own words, and she made the journey on a freighter carrying explosives. Upon disembarking in London, she went to see Hemingway at the hospital, where he had been admitted due to a car accident, singing the forty. They each went by her side and did not see each other again until the final moments of the war; six months after the peace was signed, the writer married Mary.

But before that, the curious episode of D-Day took place. Martha, as intrepid as she was tenacious, had to use her imagination and daring as she lacked a press card. What she did was hide in the toilets of a hospital ship and, when the first waves secured the beaches of Normandy, she went ashore with the medical teams disguised in a stretcher-bearer's uniform. She was the only woman among the hundreds of thousands of men who set foot on French soil that June 6, 1944. Her still husband was also there but they did not let him leave the landing craft for fear that something would happen to a literary glory of USA.

Martha's audacity on D-Day was not an isolated episode. She followed the troops as they advanced through Europe and was among the first to inform the world of the horror of the Dachau concentration camp, which she experienced on the spot . She later returned to London to divorce her; She had lasted four years with Hemingway and would take over from him with a long list of names:the businessman Laurence Rockefeller, the journalist William Walton, the doctor David Gurewitsch and the editor of Time T. S. Matthews (whom she would marry in 1954... only to divorce in 1963).

Now, if those divorces brought her something, it was her full freedom to continue exercising her profession. She was in the Vietnam War and in the successive Arab-Israeli conflicts, to name just two of the many that took place over so many decades. Missions that separated her from Sandy, the Italian orphan that she had adopted in 1949, but that did not prevent her from continuing to publish, both essay and fiction. She being septuagenarian she still traveled to Central America to report on the civil wars that hit the region in 1979 (Guatemala, El Salvador, Nicaragua...). In 1989 she did the same with the US invasion of Panama.

Of course, the years did not pass in vain and they began to take their toll mercilessly; badly operated cataracts left her half blind and practically unable to work. The time came for her definitive withdrawal, which she did not know how to cope with and in 1998, ill with cancer, she ended her life by ingesting a cyanide capsule. It was the end of the hectic life of a woman determined to be known for herself, demanding that Hemingway not be mentioned when interviewed because he refused to "be a footnote in her life" .