Barely a month after the start of World War II the British embassy in Oslo received a mysterious unsigned letter offering information detailed information on the state-of-the-art weapons that Germany was developing.

That sowed confusion in the secret services because it did not come from any known agent and a priori it sounded cheating. However, his instructions were followed and a week later a complete document arrived that has gone down in history as the Oslo Report .

It was the captainHector Boyes , Royal Navy captain serving as naval attaché to the legation, the recipient of the opening epistle. On November 4, 1939, he must have been stunned when he read the text, in which he was offered, if he was interested, even a covert way of expressing his approval:changing the greeting that the BBC broadcast made to Germany , the expression "Hullo, hier ist London" (Hello, London speaking), repeating the greeting twice.

As at first glance there was nothing to lose, so it was done and a week later a package containing the aforementioned report arrived at the embassy, seven pages typewritten, detailing the investigations of the Nazi regime in the field of weapons electronics and the companies collaborating in various programs, with express references to the wavelengths of the radars and the anti-aircraft countermeasures on which the Germans were working.

It also included production statistics for Junkers bombers and the construction date of what was to be the first Kriegsmarine aircraft carrier (although the report called it Franken , so it was perhaps confused with the tanker of the same name). More important was the review of the design of small remotely guided rockets and the description of the Rechlin airbase, where the Luftwaffe research laboratories were located.

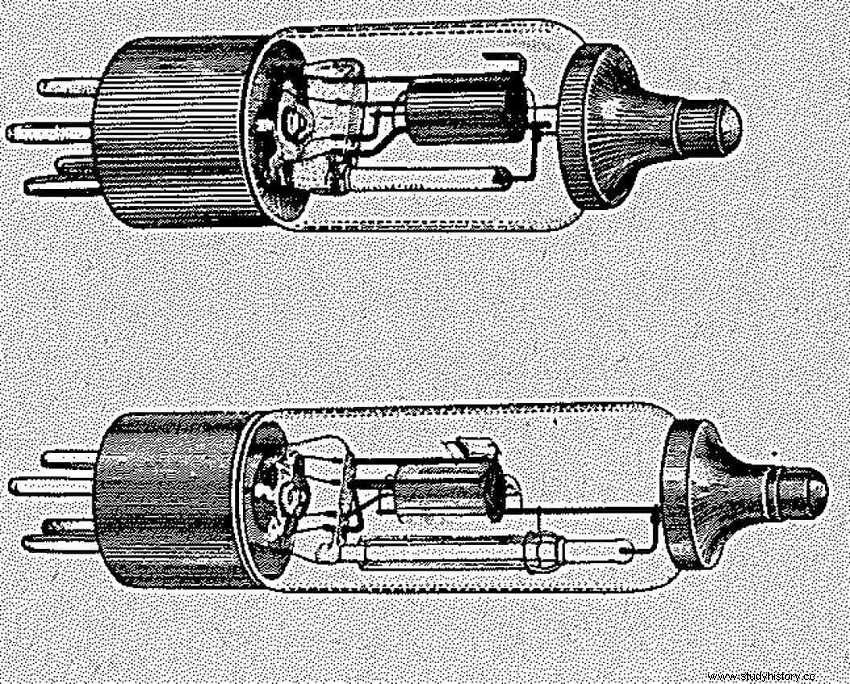

Another part of the report explained the two new types of torpedoes developed for submarines, some acoustic and others magnetic, as well as the operation of artillery shells by means of electrical fuses, which replaced the classic mechanical means. In addition, it attached one of those pieces:a thermionic valve or vacuum, capable of acting on electrical signals and that would be used as a sensor for the fuses.

Referred to MI6 (British secret service for foreign affairs), surprisingly in London he was not granted credibility and only a young physicist named Reginald Victor Jones , who would later become deputy director of the new scientific section of Intelligence, warned that the information was correct from a technical point of view, at least for the most part (there were some bugs like Junkers over-production or the aforementioned Franken confusion , which was later found to be due to the fact that the author did not always have first-hand data).

Consequently, it could only be interpreted in two ways:either it was a propaganda trick to show Teutonic technological superiority and sow discouragement in Great Britain or had they really found an informer contrary to Nazism and therefore of great value. The British command leaned towards the first option:tricks of the Abwehr , the German intelligence service; they had recently taken a bait from the SD (Sicherheitsdienst , SS counterintelligence) and it had cost them several agents, so they didn't want to risk it again.

After all, the British had just deployed their BEF in France. (British Expeditionary Force) showing Hitler that they were willing to stop him and, indeed, his presence seemed to have been so dissuasive that the Wehrmacht did not dare to confront them and settled for the invasion of Poland . In a matter of a few months, the error of that analysis would become clear on the beaches of Dunkirk.

The truth is that without knowing who the author was of the report it was difficult to make a decision with certainty. Who could have such knowledge of German research? Furthermore, why did he want to report it to the enemy? These questions remained unanswered until in the spring of 1940 the German army was on the move again, entering Denmark . It turns out that this was the country that, due to its neutrality, the informer used to send his messages.

His name was Hans Ferdinand Mayer . German, born in Pforzheim in 1895, had studied Mathematics, Physics and Astronomy at the universities of Karlsruhe and Heidelberg, obtaining a doctorate for work on electricity directed by a full Nobel laureate, Dr.Philip Lenard . In 1922 Mayer joinedSiemens to work on electronic circuits for communications and in 1936 he became director of the company's research laboratory in Berlin.

Thanks to that position he had access to extensive information about the work being carried out in the country in terms of weapons applications of electronics, also having the freedom to travel. And it so happened that Mayer was not only not a Nazi If not the opposite; the invasion of Poland persuaded him to do everything possible to end that regime.

So he went to Oslo at the end of October and he wrote the report in his room at the Bristol Hotel, making several copies on carbon paper. He also wrote a letter to Henry Cobden Turner , a British friend whom he had met working at the General Electric Company between the wars and who had helped him get a Jewish girl disowned by her Nazi father out of the country. He now asked him to maintain contact through another Danish man, Niels Holmblad . That's how the documents got to the embassy. One of the copies is currently on display at the Imperial War Museum in London.

However, the invasion of Denmark in April 1940 he frustrated the possibility of continuing with the plan and on top of that Mayer was arrested by the Gestapo in 1943, accused of listening to the BBC and criticizing the government. He was confined in Dachau but the intervention of his former teacher, the aforementioned Lenard, who was a devout Nazi, saved him from further punishment and he was transferred, passing through several concentration camps ; his intellectual level helped make his captivity more bearable, destined for radio communications. Obviously, the Gestapo never found out that he had done the Oslo Report .

At the end of the war he went to the US as part of Operation Paperclip , originally named Overcast , which facilitated the transfer to that country of German scientists who had worked on weapons issues. There he did research at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base for the USAF. He later became a professor of electrical engineering at Cornell University and in 1950 he returned to Germany , rejoining Siemens.

Reginald V. Jones revealed the existence of the Oslo Report in 1947 but he still did not know its authorship and did not find out until 1953, although in a conversation with Mayer they agreed to keep it secret to avoid possible reprisals from pro-Nazis.

In fact, not even his family knew about it until 1977, when he himself told them; he left it outlined in his will on the condition that it be made public only on his and his wife's death. Mayer died in Munich in 1980 and Jones waited until her death in 1989 to publicly unveil the enigma .