Is there anyone who hasn't seen The Great Escape, the famous film by John Sturges, starring a host of stars (Steve MacQueen, James Garner, Charles Bronson, Richard Attenborough, James Coburn...)?

It told a true story to the rhythm of Elmer Bernstein's catchy soundtrack:the mass escape of Allied prisoners from a German concentration camp during World War II. What is not so well known, perhaps because Hollywood does not pay attention to it, is a similar event that occurred in 1917, during the previous conflict, and which has consequently been dubbed the First Great Escape .

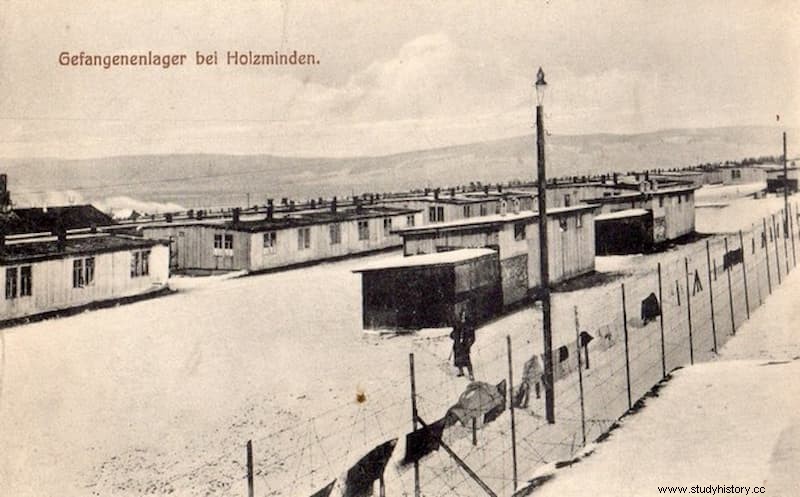

The situation was similar, although in this case it was not a concentration camp but a prison and it was not in Poland but in Holzminden , a small town in Lower Saxony founded in the Middle Ages and which spent most of its known history under the jurisdiction of the Duchy of Brunswick.

Two prison complexes were built there:one was a camp in which about ten thousand Polish, Russian, Belgian and French civilians (including women and children) were interned and another the aforementioned prison , which reused an old cavalry barracks and consisted of two barracks with four floors each. This second one was inaugurated in September 1917 to house British officers who had been captured in action.

Interestingly, as would happen later in Stalag Luft III, they all belonged to the aviation weapon. (and several of them shot down by the Red Baron ), which proved to be the most active in terms of leaks, perhaps because its members, accustomed to flying, could not bear to remain confined.

Soldiers of X Hanoverian Corps They took care of their custody, just as they did in other similar places -smaller- located not far away, in Clausthal, Ströhen and Schwarmstedt. The construction of the Holzminden prison was intended to alleviate overcrowding of prisoners , and the initial remittances were sent from the aforementioned places plus others from Freiburg and Krefeld.

All officials , because the social customs at that time separated them from the troops. The initial command corresponded to General Karl von Hanisch , who led X Corps and appointed Colonel Habrecht to deal with Holzminden.

But he was already in his seventies and ended up being replaced by captain Karl Niemeyer , whose twin brother Heinrich was also kommandant of a field, the one mentioned in Clausthal. The reason for putting the Niemeyers in charge of those sites was that they spoke English , since they had spent a good part of their previous life in Milwaukee, USA, although they say that the prisoners made fun of Karl's American accent and slang and nicknamed him Bill Milwaukee .

More than half a thousand Britons were held in Holzminden guarded by between one hundred and one hundred and sixty guards. As is often the case, some prisoners performed tasks as assistants and enjoyed a certain freedom of movement around the compound, which in addition to the two blocks -called Kaserne A and Kaserne B- was also equipped with facilities such as kitchens, toilets, coal cellar, gym or cells. of punishment, among others; all surrounded by adouble barbed wire fence that separated the architectural part from a garden area protected by an exterior wall topped with barbed wire.

Some called it "the worst camp in Germany", not so much because of the security measures as because of the hard daily life regimen , in which a poor meal -partly motivated by the scarcity that Germany was suffering at that point in the war- and the brutal treatment dispensed to prisoners - there were cases of deliberate bayonet deaths - contrasted with the situation elsewhere.

However, the British managed to survive thanks to food parcels that they received from their families and the Red Cross, which allowed them to deal with the German soldiers; in fact, in the final phase of the war they even became better provided than their captors to the point that they were mocked for wasting food. Likewise, to cope with their captivity, they practiced various sports and organized reading sessions and theater performances.

Who knows if these were the beginning of the vocation of the most famous prisoner, Lieutenant James Whale , who years later would become a prestigious filmmaker directing classic films such as Frankenstein , The Bride of Frankenstein or The Invisible Man .

Now, the aspiration of all the internal officers in Holzminden was toescape and there were attempts from the beginning, whether it was cutting the wire fences, or through the same door dressed in enemy uniforms or in the clothes of civilian workers -even women-.

Surprisingly, they were often successful, although it was another matter to avoid being captured again.; in that sense, everyone returned to the compound after a few days of escape. But the arrival of Captain David Gray in September 1917 he completely changed things; He had not been there for two months when he drew up a different escape plan, much more elaborate and ambitious because, if successful, he would allow not one but a good number of men to leave. .

His idea, enthusiastically supported by two other restless companions, Captain Caspar Kennard and Lieutenant Cecil Blain, was to dig a tunnel below the fences. Taking into account the dimensions and characteristics of the prison, the ideal was to start doing it from Kaserne B, where they were staying, not only because they carried out the work indoors but also because it was the closest point to the outside:only one ten meters , something to consider given the precarious material they had to dig, the cutlery of food.

Of course, other problems arose along the way, such as the lack of air to be able to work - which was solved by improvising a homemade bomb with what they found at hand - or the prohibition of access to the site where the tunnel entrance was located, the stairwell, which they saved by disguising themselves as subordinates until they practiced a disguised door in the attic.

For months everything seemed to be going well until Niemeyer ordered sentinels to be placed outside of the perimeter; one of the posts was placed right at the exit point of the planned tunnel, forcing it to be extended another twenty meters further on , hiding the opening in a cornfield.

It was a risk because it tripled the work and delayed the date of escape, getting fully into the summer, which was when the harvest was proceeding; but there was no other choice. And, indeed, it was not finished until the second half of July 1918, choosing to carry out the escape on the night of the 23rd .

There were eighty-six men on the list to flee who should leave depending on the effort they had contributed to the excavations, but when they were already thirty the tunnel collapsed , becoming visible and ending the operation.

They managed to escape twenty-nine , against whom an exhaustive hunt was unleashed that included a reward offer to whoever provided information. In this way the Germans recaptured nineteen, detaining them spread over several camps. The other ten , traveling on foot for two harrowing weeks, managed to reach the Netherlands , who were neutral in the conflict; From there they embarked for Great Britain, where they received a hero's welcome.

Among them were the three mentioned before who set the plan in motion and Colonel Charles Rathbornem , who was the one who had the highest rank among the prisoners and was saved in only five days thanks to the fact that he was able to catch a train, since he spoke German perfectly.

Just four months later, on November 11, the war ended. In December the prison was closed of Holzminden and, before leaving, the British officers set fire to all the furniture and fixtures they gathered. However, the barracks are still preserved today, only ironically, instead of housing enemy prisoners, they now house German soldiers.

Fonts

The tunnellers of Holzminden (Hugh Dunford) / The real Great Escape (Jacqueline Cook) / Escape from Germany (Neil Hanson) / Wikipedia.

Recommended book

The War Behind the Wire:The Life, Death and Glory of British Prisoners of War, 1914-18 (John Lewis-Stempel)