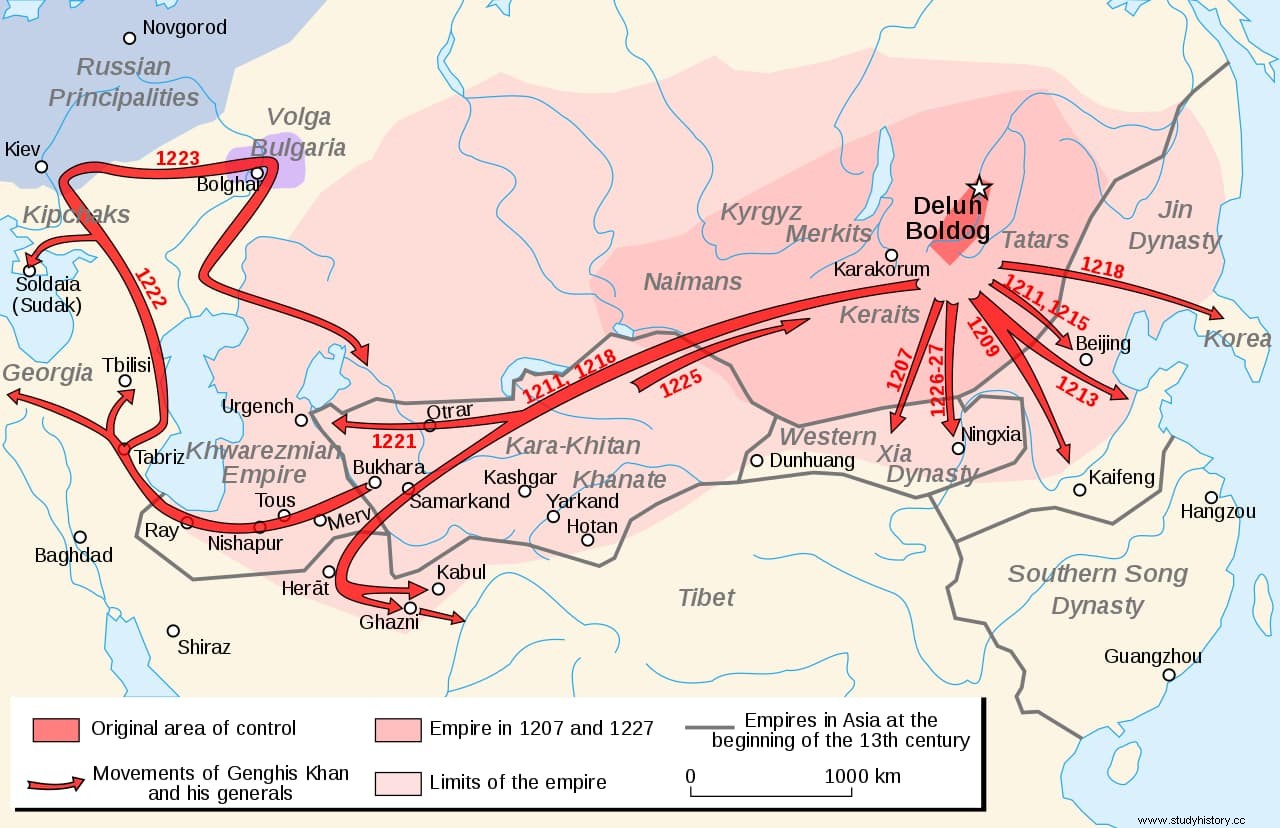

Between the last quarter of the twelfth century and the first quarter of the thirteenth, the Mongols constituted what was probably the most powerful army in the world, with which they created the most extensive territorial empire that has ever existed. As we know, it was the work of Genghis Khan, who did not suffer any significant defeat until 1223:that of the Samara Meander, at the hands of the Bulgarians, although what is known about it is so little and confused that it could very well have been exaggerated propagandistically by the victors.

And there is only evidence of this confrontation in one source, the magnum opus Al-Kāmil fit-Tārīkh (The Complete History), by the Muslim historian Ali ibn al-Athir, who reviews verbatim:

That's all (or almost, as we will see later) although we must bear in mind that Ali ibn al-Athir lived in the Abbasid Caliphate (he was part of Saladin's entourage) and the news he may have had about that confrontation, if it happened in reality, they would be few and lopsided, with a self-attributed victory by the Bulgarians to extol themselves compared to the Rus, defeated by the same enemy.

In fact, there are secondary sources that refer to a victory of the Mongols and the fact that they crushed and subjected the Cumans to vassalage, during that presumed withdrawal, only sows more doubts.

In short, there is no one hundred percent reliable account, we do not have data on the number of contending forces, we do not know how many casualties one and the other had... We do not even know who exactly commanded the Mongol army, whether Subotai, Jebe or Jochi, those who, Along with Jelme and Kublai, they had been baptized by Genghis as his dogs of war; perhaps none of them directly, because Uran, the son of Subotai, is also targeted. We also do not know who was the Bulgarian general with direct command, although we do know that of the president; it was Ghabdula Chelbir.

Ghabdula Chelbir was, from 1178 (and would remain so until 1225), the Khan of Volga Bulgaria. By this name a state was known that existed between the 7th and 13th centuries at the confluence of the Volga and Kama rivers, in the European part of present-day Russia (in the current Russian republics of Tatarstan and Chuvasia). Founded by tribes of Turkic origin (which are usually classified as Proto-Bulgarians) under Kotrag, Volga Bulgaria should not be confused with Bulgaria proper, founded a little later by other Proto-Bulgarians who continued towards the Danube.

Volga Bulgaria occupied a strategic crossroads between East and West, a location that allowed it to prosper thanks to trade and make its population multi-ethnic (Bulgarians, Arabs, Turks, Russians...), mostly of Muslim faith. Bolgar, the original capital, was the size of other large cities of its time, such as Baghdad, Damascus or Córdoba, and had economic relations with the Caliphate, Western Europeans, Byzantines, Rus, Vikings and even the Chinese. It is understandable, then, that it aroused Mongol greed and Ghabdula Chelbir had to face it.

He did not lack experience in resolving conflicts manu militari , since he had already had to fight against the Cumans (the Turkic nomads from the north of the Black Sea) to stop their expansion to the west, through Hungary, Wallachia and Moldavia. Ironically, they had now become allies against Subotai's Mongols, and things did not get off to a good start because, in May 1223, the one who was the most prestigious noyan (General) Genghis soundly defeated a Russo-Cuman coalition near the town of Kalka; the Novgorod Chronicle he says that only one in ten men survived, out of a total of between forty and eighty thousand.

Subotai's campaign, developed together with the veteran master of him Jebe of him, had begun two years earlier to take advantage of the possible confusion arising from the succession in the Khorezmite (or Chorasmian) Empire after the death of the shah; on the way back, they were to join Jochi (Genghis's eldest son) for a raid through Volga Bulgaria.

Sure enough, the first part of the plan went well; then, they marched towards the Dnieper, entering Georgia and crushing first the forces of King George IV and then doing the same with the aforementioned Russo-Cuman allies. Then came an order from Genghis for them to return to prevent exhaustion after two years of war.

Subotai and Jebe obeyed, but the return path lay through the Volga region, where news of the disaster of his allies at the Battle of Kalka had already reached Ghabdula Chelbir. Aware of the danger that his people were running, and despite the aura of invincibility radiated by the Mongols, who until then counted their actions as victories, he obtained the reinforcement of two Mordovian princes, Puresh and Purgaz, as well as Cuman troops. Of course, he must have been clear that a frontal clash with the enemy did not seem prudent, given the weakness that the country was going through at that time.

This precarious situation was due to the war waged shortly before with Kievan Rus, when the latter tried to impose a trade monopoly in the region. The contest did not have an absolute winner, but the Russians managed to conquer several Bulgarian cities -including Osel, the most important east of the Volga-, forcing Chelbir to transfer the capital to Bilär. Now, in September, a new problem arose, a priori more serious, for which he mobilized his army.

Chelbir, who had very limited troops - some estimate around thirty thousand men - decided to apply an old proto-Bulgarian tactic that, curiously, the Mongols also used to practice:feign a retreat to attract the adversary to favorable ground and thus compensate for their military superiority. The place he chose was the environment of the Zhiguli mountains, a wooded mountain range embedded in the so-called Samara meander, a great curve that describes the course of the Volga River and is characterized not only by being almost closed but also because its surface is marshy, fruit of both the water and the oil that emerge from the subsoil.

The Mongols appeared there, although it seems that they were not the totality of the available forces, far from it. In principle it should have been a larger group, but Jochi had lived up to his reputation of having a lot of initiative and instead of joining the bulk of Subotai and Jebe, as his father had ordered, he returned at his expense.

That was because he, too, had not followed their instructions to collaborate with them on the Pontic steppe campaign and made a victorious eastward campaign of his own. It is possible that this independence cost him the succession four years later, when Genghis appointed Ogodei instead of him (although he would die shortly before his father, in 1227).

The fact is that Jochi's forces were not present and surely those who marched to meet Chelbir were only the vanguard of Subotai's, led by Uran, one of his sons. Therefore, it would not be the total, which is unknown and was surely very far from those one hundred and fifty thousand warriors that are traditionally reported in Bulgaria. However, Uran must have been confident enough to go head-to-head. In fact, he put the Bulgarians to flight and, as often happened, the Mongol horsemen wanted to take advantage of the retreat by launching themselves in pursuit without realizing that they were walking into a trap.

Indeed, boxed in between the riverbed and the mountains, they were surrounded by Chelbir's troops, just as he had arranged them, and the battle had the opposite sign. Muddy in this impossible terrain, the Mongols could not maneuver and fell one after another. Some Chinese sources say they all died, but it is unlikely; Tradition has it that only four thousand prisoners were saved, from which derives a legend in which Chelbir replaced them with as many rams, hence the battle is also known today in Bulgaria by that name.

Now, this tradition comes from another paragraph of the aforementioned work, that of Ali ibn al-Athir, who after his concise narration of the battle adds:

There are historians who believe that those four thousand would rather be the total number of men from Uran, not the survivors. If so, it would be necessary to see how many Chelbir really had and to question his own casualties, which some place between five and ten thousand dead, because in that case it would be more of a Mongol victory instead of a Bulgarian one, as we said. before. It is even possible that this text is being misinterpreted, since it does not explicitly mention a battle. However, when Jochi returned to his father he knelt before him, took his hand and placed it on his head, as a sign of submission. Was he taking responsibility for the defeat, even though he had returned from his personal campaign with a big booty?

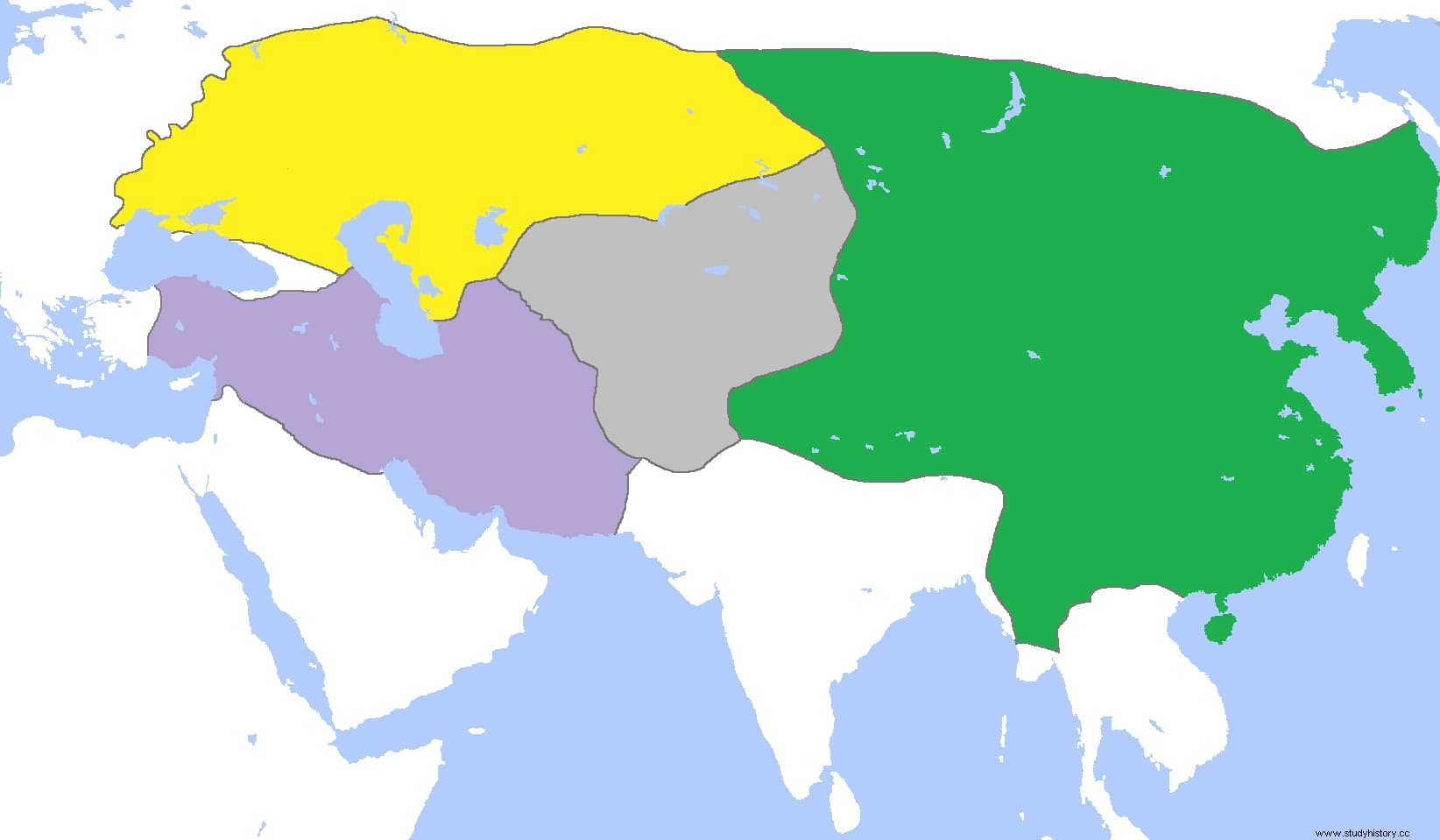

Whether it happened or not, and whoever won, the battle of the Meander of Samara has gone down in history as the only one lost by Genghis Khan. However, its significance was very limited, although Bulgarian historiography considers that it served to prevent the incorporation of Kievan Rus' into the Golden Horde (the name that would be given to the ulús or territory bequeathed by Jochi to his descendants) and therefore The theory arose that Samara was somewhat oversized so that the Russians would remain in debt. In the short term there was a great misfortune for the Mongols:the death of Jebe during that return trip, when he fell ill with a fever; it was early in 1224, shortly before meeting with Jochi to return together.

But Subotai and Batú (the son of Jochi, who in addition to inheriting the Blue Horde, that is, the east of the empire, had snatched the White Horde, the west, from his brother Orda) appeared again on the horizon in 1236, taking advantage of the fact that Chelbir he had also died in 1225 and internecine struggles ravaged Volga Bulgaria. This time they managed to subdue it, breaking it up into small vassal states that were autonomously incorporated into the Golden Horde and putting an end to the country as such.

Fonts

The Chronicle of Ibn al-Athir for the Crusading period from al-Kāmil fī’l-Ta rikh. The years 589–629/1193–1231, the Ayyūbids after Saladin and the Mongol menace (D.S. Richards)/Genghis Khan's greatest general:Subotai the Valiant (Richard A. Gabriel)/In the service of the Khan. Eminent personalities of the Early Mongol-Yüan period (Igor de Rachewiltz, Hok-lam Chan, Hsiao Ch'i-ch'ing, Peter W. Geier, and May Wang, eds.)/Wikipedia