The most common form of succession of a king is from father to son, but historically there have been others. The Spartans, for example, had an elective monarchy which, moreover, was a diarchy. The Romans also elected their sovereigns, at least up to the fifth, as happened with the Visigoths, the Aztecs, the Holy Roman Empire and many more, it is true that most ended up becoming hereditary regimes. Of all of them, one of the most original was that of medieval Russia:called lestvitsa or broken , was that the throne passed from brother to brother.

The term comes from the ancient Slavonic language introduced by Saints Cyril and Methodius, the Byzantine missionaries who, from Thessaloniki, evangelized Eastern Europe. They used it, above all, to translate the Bible called Septuagint , which was in Koine Greek (the one that spread in Hellenistic times, after Alexander the Great) and was the most widely used among devotees of what would become the Orthodox faith in the 11th century.

Therefore, the language used by Cyril and Methodius was closely linked to religion and is therefore known as Church Slavonic. It is a synthesis of Greek, East Slavonic, Hebrew and Latin, and has its own alphabet, Glagolic, a combination of all of them.

That was between the years 862-863 AD. The important thing is that the word in question is translated as ladder , which in this case tells us what the method of succession to the throne was like in Kievan Rus' and in Muscovy or the Great Principality of Moscow.

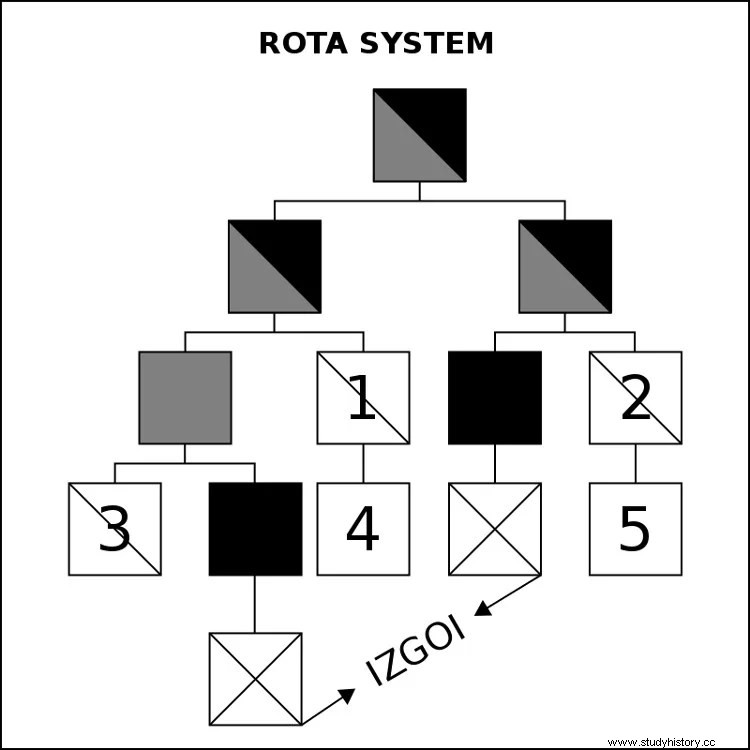

In fact, the usual thing in Spanish is to refer to it as rota system , because there is another term in Old Slavonic, roda , which means "related to the family". In short, the crown was transmitted not from father to son but from one brother to another, normally up to the fourth of them, then passing the rights to the eldest son of the first.

Although it is strange, in fact it was already practiced in other places, such as the Viking kingdoms settled in Great Britain and Ireland. Even the Ottoman Empire and, in contemporary times, Saudi Arabia and Tunisia, had something of the sort. But in medieval Russia its origin had its own name:Yaroslav I the Wise , prince of Novgorod and kyiv, during whose reign Kievan Rus reached its maximum splendor.

This was a state formed by a federation of Slavic tribes and founded by Prince Oleg in the 9th century to ward off Khazarian incursions, later expanding under Sviatoslav I and Vladimir the Great (which introduced Christianity).

Yaroslav, son of the latter, seized kyiv from his half-brother Sviatopolk and incorporated it into the newly created Republic of Novgorod. Despite being ruthless with his brothers, he earned the nickname of Sage both for having turned his country into a small local power (he put an end to the constant threat of the Pecheneg nomads and even wrested Crimea from the Byzantine Empire; he even attacked Constantinople) and for promoting a policy of cultural patronage. The problem was leaving an heir, because his own experience told him that everything would probably end in fraternal war.

Yaroslav had one child from his first marriage to Anna of Swabia and later six more by his second wife, Astrid-Margaret of Denmark. Fearing that they would not conform, he distributed his possessions among all, giving each one a principality in hierarchical order. The firstborn was the Grand Prince and ruled in the capital, kyiv. Upon his death, the second would succeed him, this one the third and so on up to the fourth, in a staggered manner (hence the denomination of ladder given to that system). The next in the line of succession were the children of the eldest, followed by those of the other siblings (by age) and then, following the same sequence, grandchildren, great-grandchildren, etc.

Condition sine qua non it was that the father had reigned; otherwise, the princes were excluded and, in fact, they were called izgói , which means orphans, as outlined in the legislative code entitled Rúskaya Pravda . That doesn't mean they were left with nothing; they inherited from their fathers and often held important positions, such as governor. An example of izgói it was Rostislav Vladimirovich, son of Vladimir Yaroslavich (Yaroslav's first-born son by his first wife); Vladimir died before his father, so he could not reign and Rostislav thus lost his right to the throne at fourteen years of age, although his uncles gave him the frontier principalities of Volhynia and Hálych (Galitzia), which he expanded with the conquest of Tmutarakáñ (a city built on the ruins of the Greek colony of Hermonasa, on the shores of the Black Sea).

Not all historians agree that the system broken was institutionalized, since some believe that the frequent fratricidal wars show that it was not so; others, on the other hand, believe that these conflicts precisely demonstrate their existence, being a consequence of the development of the hierarchical succession and its progressive complication. In any case, it was the year 1097 when the city of Liúbech, in the Ukrainian oblast of Chernigov, hosted a council of princes in which important decisions were made for the future of the succession system, such as the creation of patrimonial estates on the margin that, in In practice, they were almost independent principalities.

This resulted, in practice, in the regional disintegration of Kievan Rus', although nominally it continued to exist until the Mongol invasion of 1240. It is also true that this decline was not only due to political disunity but also to the economic crisis that it supposed the weakening of the Byzantine Empire and the consequent decline of the commercial routes that kyiv maintained with Constantinople. But the system broken it did not disappear, since it remained in the Principality of Moscow, continuation of the Rus; after all, it had been formed in its northern territories, and Ivan III would even become the titular Grand Prince of all Rus' in the 15th century.

Ivan was the son of Basil II, who got into a civil war for the Moscow throne, first with his uncle Yuri, who claimed him by right of rota , and then with his nephew, Dimitri. In the end Basil II prevailed, who would put an end to the collateral succession by naming his son Iván as his successor. Later this one, in his last wish, arranged that after dying the domains of his relatives should pass directly to the Grand Prince instead of to the heirs of the other princes, as was customary. In this way, he put the last shovelful of earth on the broken system and, incidentally, laid the foundations for Russian unification. His grandson, Ivan IV the Terrible , would be crowned the first tsar.