In a time before any idea of dignified treatment of the vanquished enemy, in times when being defeated on the battlefield was an open door to the most bloodthirsty atrocities, in short, there was an episode in the Middle Ages that even surpassed what was customary and passed down to posterity as the echo of that terrifying reality of war. It starred the Byzantine emperor Basil II, who earned the unattractive nickname Boulgaroktonos (Slayer of Bulgarians), after having commanded to blind the thousands of captives of that origin that he did in the Battle of Kleidon.

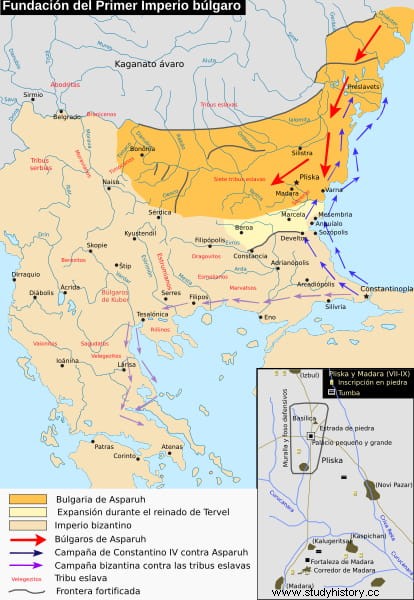

At the beginning of the 11th century, the Byzantine Empire exerted to the west and north, specifically on Bulgaria, the same pressure that it received from the other side by a Fatimid Caliphate in full expansion. Actually, it was not a new situation, since its origins date back four hundred years before, when Asparukh, a khan of the Dulo clan, from the Ukrainian plains, took advantage of the fact that Constantinople's hands were tied, besieged by troops of the Umayyad Caliphate of Baghdad, to guide his people beyond the Danube and install them in an area called Ongala, which roughly coincided with southern Bessarabia.

These proto-Bulgarian invaders numbered close to a million people, too many to be able to expel effectively. That is why Emperor Constantine IV, once he got rid of the Muslim siege, allowed them to stay but in exchange for concentrating in a fortified and guarded town. However, Constantine fell ill and had to return to the capital, which spread discouragement among the soldiers in charge of said surveillance. This was not lost on Asparukh, who took advantage of the weakening to defeat them in 680 and continue advancing towards Byzantine Thrace.

The emperor preferred to reach an agreement and accepted his presence by hiring that army to fight the Muslims, in what is considered the birth of the First Bulgarian Empire. Of course, the relationship between the two parties was doomed to deteriorate and the inevitable friction led them to war on several occasions, turning them into rivals. Bulgaria grew, reaching Transylvania to the north and the Greek peninsula to the south, and seriously threatening Byzantine existence in the time of Tsar Simeon I. However, in the year 968 things changed:Prince Sviatoslav I, of the Rus of kyiv, which had initiated an aggressive policy of military expansion by conquering Khazaria, set its sights on the west and, following a proposal from Emperor Nicephorus II, began a campaign against the Bulgarians.

Sviatoslav's troops, made up of six thousand Pecheneg mercenaries (also called Patzinakos, a semi-nomadic people from the steppes of Central Asia) defeated the Bulgarian Tsar Boris II in the Battle of Silistria, seizing the northern part of the country from him. Then, cunningly egged on by the Byzantines -true masters of intrigue-, they turned against kyiv, forcing the prince to return to liberate the city from the siege to which they were subjecting it. In this way, Nicephorus II was the great beneficiary, since he kept the gains from Bulgaria and even captured Boris II in 971. Sviatoslav did not give up and after reorganizing he returned to the fray, taking over Thrace, but the conflict escalated. encysted; Nicephorus was succeeded by John I Tzimisces, who finally defeated the Kievan and forced him to withdraw permanently (by the way, he was killed by a Pecheneg khan paid by the emperor).

Boris II had to give up the Bulgarian throne and the eastern half of his country remained in the hands of the Byzantine Empire, but the other half remained independent and resisted any attempts at occupation. This is how things stood in the year 976, when Basil II rose to power in Constantinople, as severe a military man as he was an efficient administrator. In front of him was Samuel, a former Bulgarian general who co-ruled with Roman I and was not only unwilling to hand over his country, but aspired to recover the lost territory to the same extent that his adversary wanted to appropriate it. what was left Basilio suffered an important defeat in 986, in the passage of Trajan's Gate, and this had repercussions in such a way that the empire was involved in a civil war, which gave Samuel a free hand to reconquer almost everything at the expense of Serbs and Croats and even march on Greece taking advantage of the parallel Fatimid pressure.

The Byzantines were able to stop him in an unexpected and forceful way in 996, at the height of Corinth, in the Battle of Esperqueo. Samuel's army was destroyed, Roman was taken prisoner and Samuel himself was able to escape at night, after feigning death in the field; with it, his plans to restore the power of Bulgaria vanished. Thus, although Basil had been presented with an extra problem, the Muslim threat that we were saying, already well into the 11th century he was able to go on the counterattack with Hungarian help and claim a new victory in Skopje that opened the doors of Thessaly and southern Macedonia. . The Bulgarians were not able to stop that wave and fought a progressive retreat that they tried to break in the Battle of Kreta, near Thessaloniki; It was in 1009 and they lost again. And although the Byzantines did not obtain decisive results with those triumphs, slowly but inexorably they were wearing down, exhausting, the enemy.

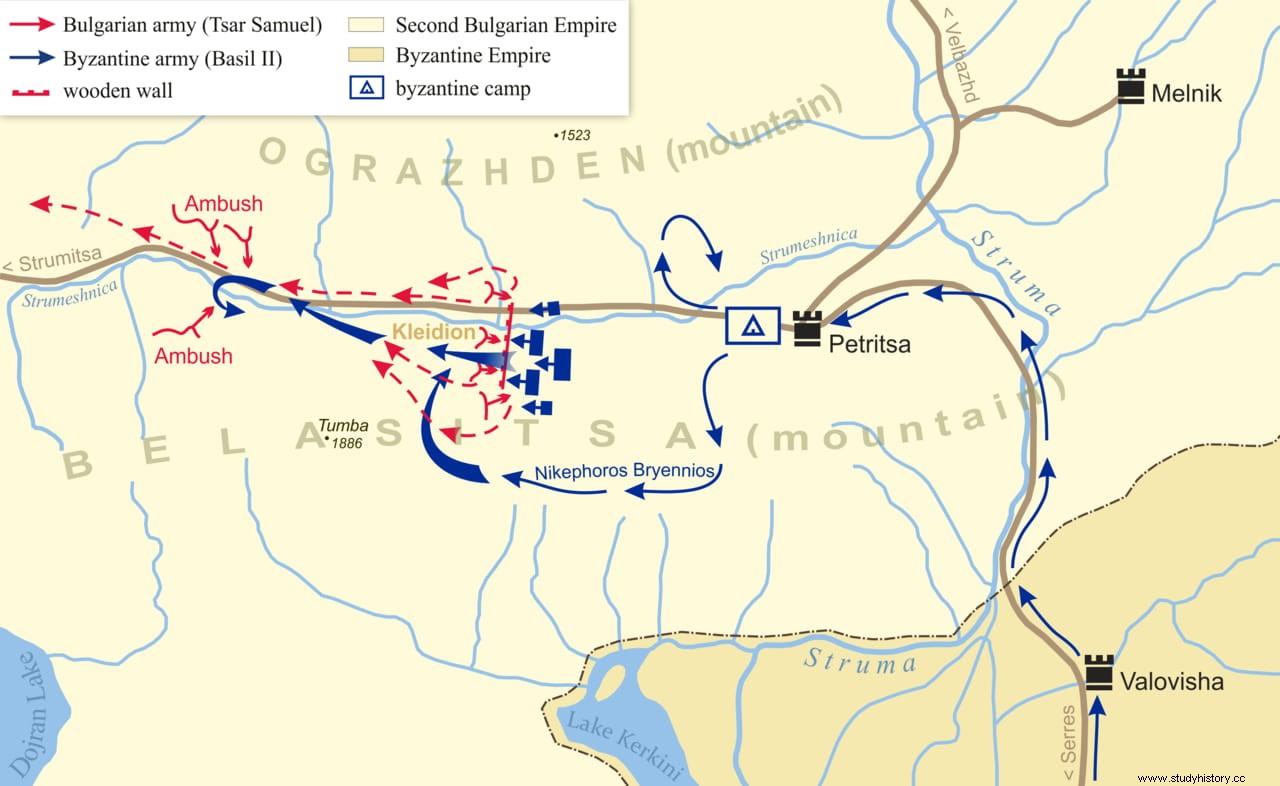

Samuel had been elected Tsar after his death in 997, in a prison in Constantinople, by Roman. Of course, the Byzantines did not recognize it as such, despite having the endorsement of Pope Gregory V, since they considered that the abdication of Boris II meant that Bulgaria had ceased to exist as a state, so that its successors would be nothing more than rebels. . But at that point, after so many defeats, Samuel did not enjoy a firm position among his own, so in the year 1014, determined to stop the invader once and for all, he concentrated his men in the valley of the Strymon river, which was the natural passage that the Byzantine armies used to enter Bulgaria. Based on the village of Kleidion (present-day Klyuch), he built a series of defensive systems that included moats, ditches, and a wooden wall with towers.

He managed to gather forty-five thousand men, the chronicles say with more than probable exaggeration (it is estimated that they would be half). Basil II picked up the gauntlet and launched a new campaign, the command of which he handed over to Nicephorus Xiphias, governor of Philippopolis and veteran conqueror thirteen years earlier of Pliska and Peslav, the ancient Bulgarian capitals. In front of him, the local troops were led by Gabriel Radomir, son of Samuel, who successfully resisted Byzantine attempts to force the way. He helped him, yes, the cunning of his father by sending an expedition under the command of General Nestorisa with the mission of attacking Thessaloniki and thus distracting the enemy forces. However, the plan went awry when Nestorisa was finally defeated by Governor Theophylact Botaniates, who then joined the forces fighting on Kleidion.

Now, the arrival of those reinforcements was of no use; at least at the beginning. Samuel's defenses were revealed to be impregnable and seemed capable of destroying the Byzantine objective, so it was necessary to look for an alternative. The one that was found is part of the classical imaginary in these cases:just as the Persians did at Thermopylae and others in many similar situations, Nicephorus Xiphias led his troops to surround the mountains, marching down the rugged slopes, until surprising the Bulgarians for their rear. These suddenly had to attend two fronts and that allowed the main force to storm the wall, sowing chaos. A retreat to Mokrievo was ordered but that had already become a man for himself.

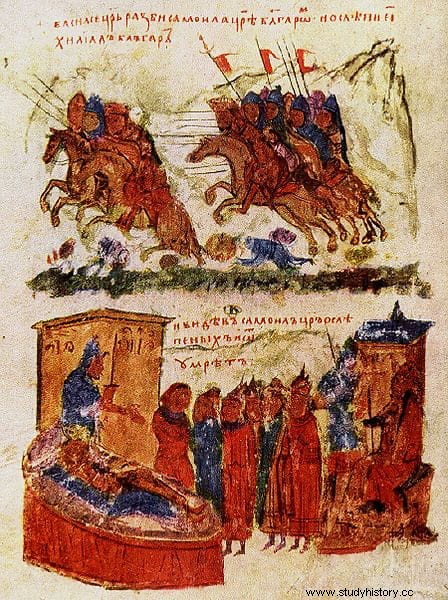

Samuel was able to escape thanks to the horse given to him by his son, who stayed to try to reorganize the defense from the neighboring town of Strumitsa. But it was already useless, although there was still occasion for some remarkable action that, however, would bring fatal consequences. Gabriel Radomir himself starred in it before Theophylact Botaniates, who had been ordered to destroy the fortifications. He had just finished that mission and was returning to the main camp when he was ambushed by what was left of the Bulgarian force commanded by the imperial scion, who engaged the other personally by impaling him with his spear. Basilio II deeply felt that loss; so much so that, in his anger, he ordered the prisoners to be separated into groups of a hundred and then ninety-nine of each group to be blinded, leaving the one left with only one eye so that he could lead the others. At least that's what the legend says.

According to the sources of the time, there were about fifteen thousand captives. Current historians reduce the figure by half -assuming it were true-, but it was still an impressive punishment, even when it was the usual one in those times for the seditionists. As we said before, Basil II earned the nickname of Boulgaroktonos , which means killer of Bulgarians. In fact, that decision was so brutal that two months later, when he saw that pathetic procession of those who used to be his soldiers appear, Samuel suffered a heart attack and died. He was succeeded by Gabriel Radomir, assassinated within a year during a hunt -at the behest of the Byzantines- by his cousin Iván Vladislav, who proclaimed himself Tsar to fall dead in 1018, at the Battle of Dyrrachium, after breaking the promise to submit to had made Basil II.

That defeat and the death of Iván supposed the definitive demoralization of the Bulgarian boyars; many, starting with Nestorisa, agreed to surrender in exchange for keeping their titles. Thus ended the resistance and, consequently, Bulgaria became another province of the Byzantine Empire. Although the truth is that it hardly took half a century to return to being a second-rate power. And it is that Basilio II, who did not marry or father known descendants, did not have successors of his height and the throne would pass into the hands of his brother, inferior in everything.

The application of a process of Hellenization to the Bulgarians and the abusive tax system of the pronoia (which forced the peasants to pay in currency, instead of in kind), strengthened the Bogomilita movement (a Manichaean ascetic sect) and again broke the tranquility. In 1185 Bulgaria achieved its independence…until the arrival of the Ottomans.