Amiens Cathedral, declared a Historic Monument in 1882 and included in the World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1981, is a reference in its style and also brings together a series of curious elements that give it a special interest. One of them is the famous labyrinth that paves the floor of the nave; another, the projection of night light on the cover to give it a spectacular polychrome appearance; there is also a relic as unusual as the skull of Saint John the Baptist. But perhaps the most peculiar is the iron belt, they say Spanish-made, with which the building was surrounded to prevent its collapse.

Amiens is a small French city crossed by the Somme river whose main tourist attraction, apart from the house-museum of the writer Jules Verne, is the aforementioned cathedral church, a classic Gothic jewel built from the year 1220 on the remains of a previous Romanesque temple that had been destroyed by the fire caused by a lightning strike.

The idea of erecting something exceptional was not only intended to compensate for that loss but also to give adequate shelter to what was considered one of the most important relics of France, the frontal of the skull of Saint John the Baptist, which a crusader knight had brought from Constantinople two decades before, turning the place into a destination for floods of pilgrims -especially epileptics who hoped to be cured of what was then called San Juan's disease-.

The architect chosen to design the new temple was Robert de Luzarches. However, he was not long because, at the request of King Philip II the Augustus , in 1228 he left the job to take charge of the construction of another famous cathedral, that of Notre-Dame de Paris. By then there was already enough standing because work was done quickly, thanks to the fact that the economy of Amiens was going through a buoyant stage by possessing the monopoly of a plant used for dyeing and thus originating a growing bourgeoisie that collaborated financially with important donations.

Robert de Luzarches left after two years and was replaced by Thomas de Cormont, possibly a disciple of his, who would later take charge of another important Parisian church, the Sainte-Chapelle. Cormont directed the works until 1228, when he died and was succeeded by his own son, Renaud. It was he who completed the nave and closed the walls of the vaults, starting the transept and raising the façade.

Towards 1240 the problems arrived. The economy shrank, money ran tight, and jobs slowed for eighteen years. Paradoxically, a fire gave a new impetus to the company, finishing the choir in 1269 and the project being considered finished in 1288. The towers of the façade were missing -which were never built- but the cathedral was already operational and, in fact, in 1385 the wedding between King Carlos VI el Loco was celebrated there and Elizabeth of Bavaria-Ingolstadt.

However, minor things were still being added. For example, eleven side chapels that, as they did not appear in the original plan, required moving the buttresses of the naves outwards and, consequently, lengthening the flying buttresses. Quite a clumsiness that became a danger, since these flying buttresses, in charge of counteracting the thrust of the choir ceiling, were too weak for that pressure exerted by the enormous height of the arcades (42.3 meters) of the triforium naves. To solve this, they were reinforced with a second line of lower buttresses… which caused the appearance of cracks.

Everyone was aware of the risk of collapse, since in 1284 the dome of the neighboring Beauvais Cathedral had collapsed due to a similar cause, when two apse buttresses gave way. Perks of the rivalry, because until then the naves of the Amiens cathedral were the tallest in Europe and that of Beauvais was erected with the aim of surpassing it.

In 1573 it suffered a second collapse that left it deeply battered (until today, it is still in a very delicate state), hence the structure was later surrounded with iron clamps to act as a containment, although that took away flexibility from the whole. and cracked it. It was a solution copied precisely from the one applied by Pierre Tarisel in Amiens.

Around 1482, Tarisel had replaced the late Guillaume Postel as masonry master builder and analyzed the state of the building, considering the second pillar of the choir and the outer walls to be dangerous. The pillar was secured in 1497 and six years later the same was completed with the others. But the issue of the exterior wall was missing, which, cracked, threatened to overcome by the force of push that made the vault of the choir. Tarisel solved it by wrapping almost the entire perimeter with what they call in French chainage , an iron belt that passed through the clerestory and the arms of the transept.

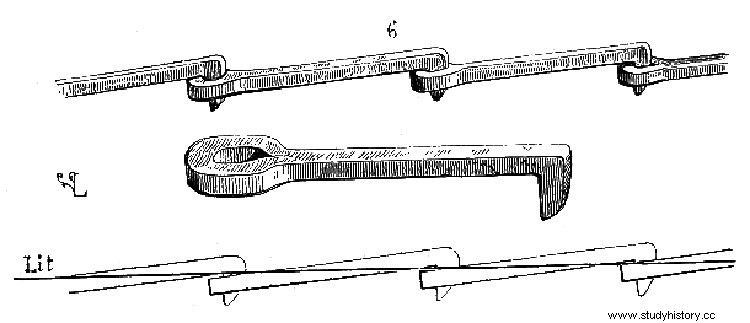

Said belt, a kind of chain based on different types of wrought iron links (a material chosen for its ductility), was commissioned from Spanish ovens because the most appreciated iron was made there at that time. Or so says one version, since another places the origin in the Abbey of Fontenay, a Cistercian monastery in the Burgundy region so large and prosperous that it even had steel forges. In any case, it was a series of rods, bars, clamps, straps and staples that, once transported to Amiens, were riveted to the red-hot stone, tightening them as they cooled to form the containment strip.

It wasn't really a new idea; Previously, this type of reinforcement was applied only in wood, which caused secondary problems due to the tendency of this material to swell with humidity and even rot. Of course, iron also had its drawbacks:not only did it rust (something that was prevented by wrapping it in lead) but, like wood, it could swell. Even so, it was a system that spread from now on, due to the success it had in Amiens.

And it is that there, after everything was completed in less than a year and taking into account that the cathedral is still standing, it seems that they hit the right key. In fact, the belt is still preserved in situ , as happens in other buildings of the same type such as Chartres, Sainte-Chapelle, St. Quentin or Westminster Abbey. In Beauvais it was removed in the 1960s but it had to be replaced, reinforced with steel, when it was found that the wind made the structure sway too much; nobody wants to risk another disaster.