In the article that we dedicated to the names of women in ancient Rome, we already said that the Roman nomination was more complex than is believed. Both in cinema and in literature we have become accustomed to seeing the typical compound names but in reality that did not obey free will but rather rules. In fact, these were not exactly compound names as we know them today; each word had its reason for being and there were not even two but three, what was known as "tria nomina", something that we have news of at least since the second century BC:praenomen, nomen and cognomen, although one could add a fourth, the agnomen.

However, although there is a tendency to see the three-name system as the culmination of Roman nomenclature, it is actually an evolving and changing process. If the tria nominates was the norm during the republican era, the new aristocracy of the imperial era was characterized by what Benet Salway calls binary nomenclature , a polyonym that used several demonyms.

Polyonymy (having many names) was generalized by a new practice during the imperial era, the obligation that many testators imposed on their heirs to adopt their name in order to inherit. An example of this is Pliny the Younger. His birth name was Cayo Cecilio Segundo, son of Lucio Cecilio Cilo. His parents dying as a child, he was adopted in AD 79. by his maternal uncle Gaius Plinio Segundo (Pliny the Elder), changing his name to Gaius Plinio Cecilio Segundo. This testamentary adoption achieved his objective, since the heir has been remembered as a Pliny and not as a Cecilio.

Names acquired after testamentary adoption tended to occupy the leading position. But there were no established limits for the names obtained in this way, so from one generation to another they were added. There came a time when many Roman nobles had a huge string of names.

The culmination of polyonymy is found in the consul of the year 169 AD. Quinto Pompeyo Seneción Sosio Prisco, who had a name composed of no less than 38 elements, which comprise 14 different sets of names resulting from family and social relationships accumulated over three generations.

His full name, in the original Latin, was:Quintus Pompeius Senecio Roscius Murena Coelius Sextus Iulius Frontinus Silius Decianus Gaius Iulius Eurycles Herculaneus Lucius Vibullius Pius Augustanus Alpinus Bellicius Sollers Iulius Aper Ducenius Proculus Rutilianus Rufinus Silius Valens Valerius Niger Claudius Fuscus Saxa Amyntianus Sosius Priscus.

As you can see, there was also no problem in the sets of names repeating some term. In any case, such a bulky nomenclature was unwieldy for normal use, and was usually abbreviated, although without a coherent criterion.

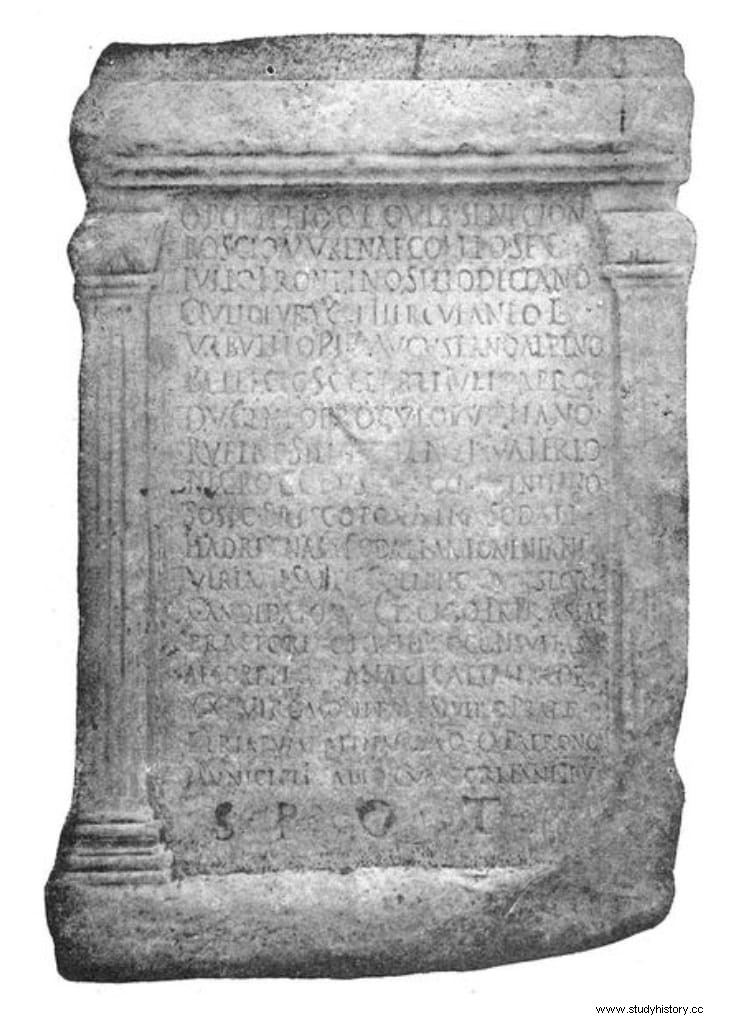

It is possible that there were many other similar cases, even with even longer names, but his is the longest attested since it is preserved in an inscription found in ancient Tibur (modern Tivoli, a few kilometers northeast of Rome). The inscription reads:

In it, in addition to his name, his political career is detailed. He was quaestor in AD 162. at the behest of Emperor Marcus Aurelius. The following year he would be appointed legate under the orders of his own father, who was proconsular governor of the province of Asia (comprising almost the entire western part of the Anatolian peninsula), and held the position of praetor around 167 A.D.

In the year 169 AD he was elected consul alongside Publius Celius Apollinaris. At the end of his term, he was appointed praefectus alimentarum (responsible for supplying food to Rome), and finally, following in his father's footsteps, he was appointed proconsular governor of Asia.

It is known that he was married to Ceionia Fabia (possibly not the sister of Emperor Lucius Verus of the same name), and that they had a son named Quintus Pompey Sosius Falcon, who was consul in 193 AD. and that, surely, he had a much longer name than his father by including those of his maternal family. But we cannot know that. What we do know is that he opposed Emperor Commodus, and upon his death the Praetorian Guard offered the throne to Falcon, who refused.