That the days have 24 hours is a long-established convention, which is also related to the rotational movement of the Earth. Pliny the Elder already expressed it as a fact that left no room for doubt:

But, as surprising as it may seem, the hours did not always last the same. And it is that before the existence of clocks, even after the invention of sundials, it was difficult to keep track of time.

That is why in ancient Rome, just as the Greeks had done before, a method as simple as it was practical was applied:from the time the sun rose until it set there were 12 hours, and another twelve from when it set until it rose again. Although this only since they began to use the sundial in 293 BC, installed according to what Pliny the Elder tells us in the temple of the god Quirino. Before that days were not divided into hours, and in fact the word was not even mentioned in the Twelve Tables, where only sunrise and sunset, and the periods before and after noon, were mentioned.

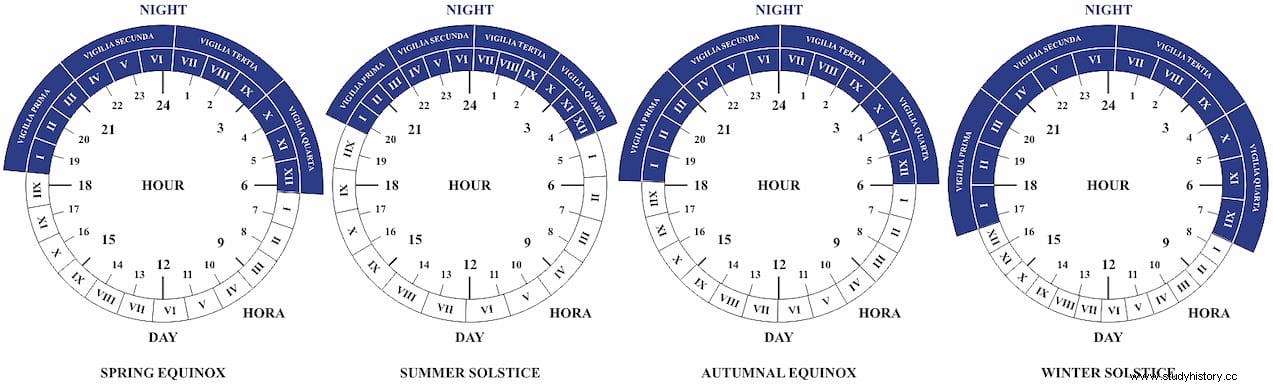

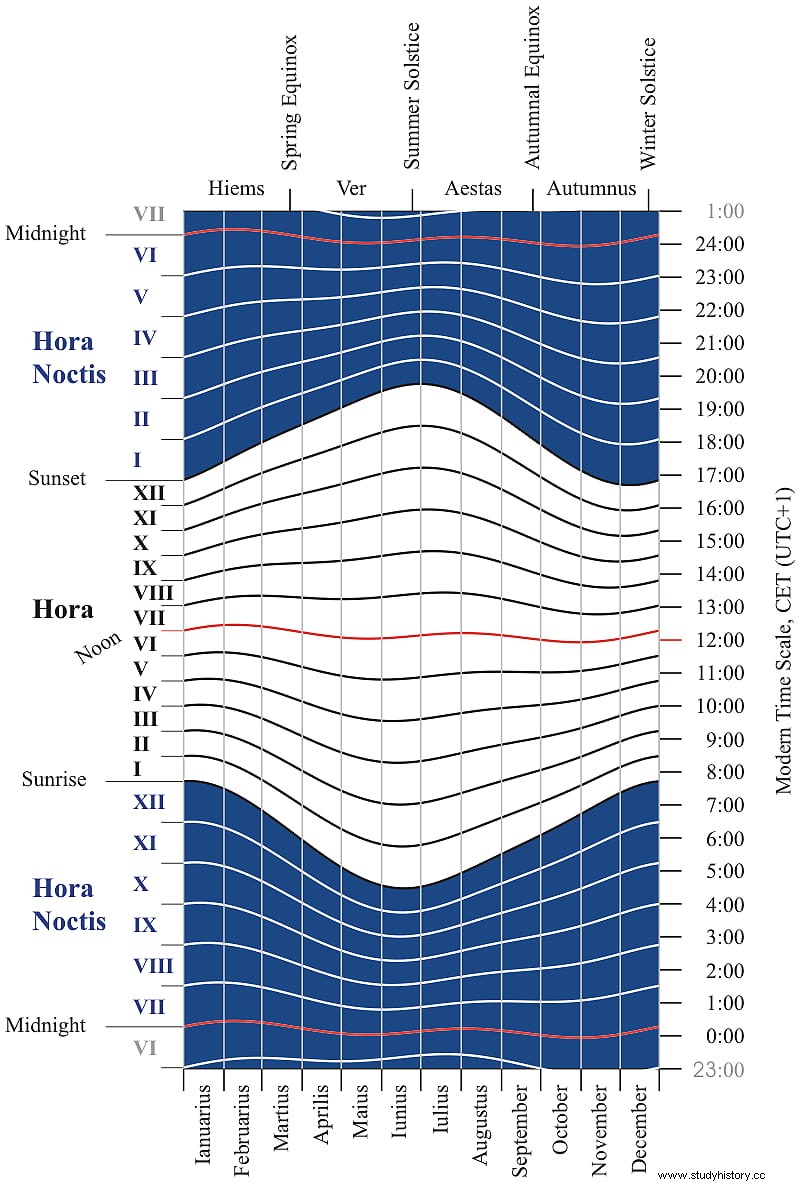

One hour of the day therefore corresponded to 1/12 of the daylight time. This meant that the duration of each hour was different depending on the latitude and the time of year. Because while the hours of light and darkness are practically the same throughout the year at the equator, the time of light is shorter in winter and longer in summer in the rest of the planet, with a more pronounced difference the further north or south go.

Thus, at a latitude similar to that of the city of Rome, one hour of light at the summer solstice lasted about 75 minutes, while one hour of light at the winter solstice lasted 45 minutes (however, it was not until the Middle Ages that subdivided hours into minutes and seconds). Because the time of light in the summer solstice lasted six hours more than in the winter solstice, and this made both the first and last hours dilate.

According to Ray Laurence, this is where the greatest differences were concentrated, since the central hours such as the sixth and, in particular, the seventh, when most of the work was resumed after the siesta (from the sixth hour after lunch) suffered little variation. In fact, the seventh hour began at the same point in time in both summer and winter.

Néstor Marqués in his book A year in ancient Rome collects the structure of a natural day (different from the civil day, which began at midnight and lasted until the following midnight):the natural day began at dawn with the solis ortus or sunrise; then came the morning (mane ) followed by the meridies or noon, and after it the afternoon (postmeridiem ). The last hour of light was the supreme , followed by the solis occasus , the sunset. Just before sunset (vwait ) the crepusculum occurred , giving way to the night (nox ). It was bedtime (concubium ) before the media nox arrived . From there the imtempesta nox spread , until finally the roosters crowed again in the gallicinium during the last moments of darkness (ante lucem ) and the first lights made their way (diluculum ) that preceded a new dawn.

Each hour received a name numbered from 1 to 12, that is, prime hour , second hour , third hour , etc. And to differentiate the hours of the day from those of the night, prima diei hora was specified. (first hour of the day) or prima noctis hora (early evening).

The Romans were perfectly aware of this difference in the length of the hours, even more evident when they began to use sundials and water clocks. Pliny the Elder, when he speaks of the parallels in which the world is divided says:

It would not be until 159 BC, when Publius Cornelius Scipio Nasica installed the first water clock (brought from Greece) in the Emilia del Foro basilica, that the hours of day and night were divided equally.