In the early summer of 55 B.C. Three years had passed since Julius Caesar had begun his conquest of Gaul. At that time the eastern border of the new provinces was located on the Rhine. The Germanic tribes on the east side of the river launched raids to the west under the protection of this natural border.

But on the other side of the river there were also tribes allied with Rome, such as the Ubios. They offered Caesar ships for the legions to cross the river and attack the Germanic tribes.

However Caesar rejected the offer and decided to build a bridge instead. This would demonstrate not only his support for the Ubian allies, but also Rome's ability to take the war to the other side of the border whenever it wanted. In addition, as he himself wrote, that he considered ships unsafe, this was more consistent with his own dignity and that of the Roman people.

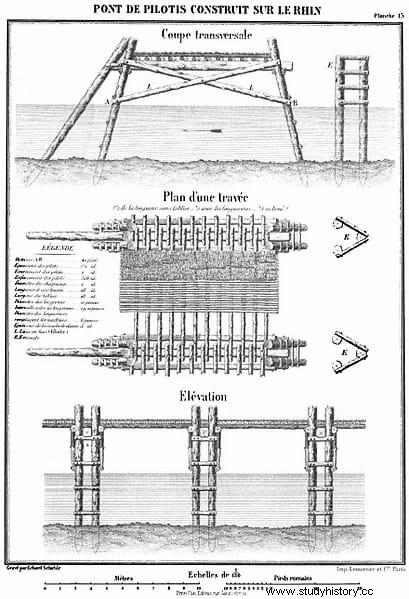

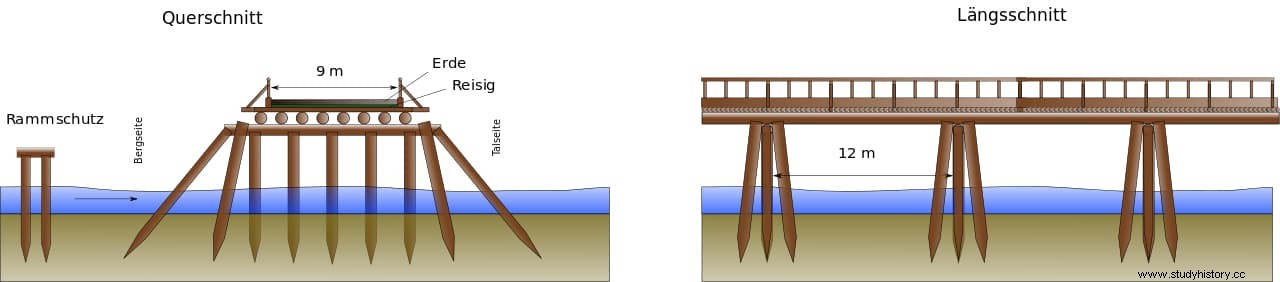

The construction was carried out between present-day Andernach and Neuwied, downriver from Koblenz, an area where the depth of the river would be up to 9 meters. On both banks, watchtowers were erected to protect the entrances, and pilings and barriers were placed upstream as a measure of protection against attacks and debris carried by the current.

Caesar's 40,000 soldiers built the bridge in just 10 days on double wooden pillars that were driven into the riverbed by dropping a huge and heavy stone on them as a mace. The construction system ensured that the higher the current, the closer the parts of the bridge were held together.

It is not known who was the engineer responsible for this new bridge construction technique, which had never been used before. Cicero suggests in a letter that his name was Mumarra, although the possibility that he was Marcus Vitruvius Pollio (the architect author of the famous Ten Books on Architecture ) should not be ruled out. ), who was with Caesar. It is estimated that the length of this bridge could have been between 140 and 400 meters, and its width between 7 and 9 meters.

Once it was finished, Caesar crossed with his troops to the other shore, where the Ubios were waiting for him. He then learned that the Sicambrian and Suevian tribes had retreated to the East in anticipation of his arrival. Not being able to put up a fight and after destroying some towns, Caesar decided to turn around, cross the bridge again and knock it down behind him. It had lasted 18 days.

Two years later history repeated itself. Near the place where the first bridge had been and about 2 kilometers to the north (possibly next to present-day Urmitz), Caesar built a second one, although this time he did not go into the details.

Like the previous time, the Suevi, seeing what was coming their way, retreated back to the East, abandoning their villages and hiding in the woods. Caesar returned to Gaul and destroyed the bridge again. Only this time he single-handedly knocked down the end that touched the eastern shore, erecting defense towers to protect the rest of the bridge.

Caesar's strategy produced the desired effect. He demonstrated the power of Rome and his ability to cross the Rhine at will at any time. Thus Julius Caesar secured the borders of Gaul and for several centuries the Germans refrained from crossing them.

It also allowed the Roman colonization of the Rhine Valley, where permanent bridges would later be built at Castra Vetera (Xanten), Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium (Cologne), Confluentes (Koblenz), and Moguntiacum (Mainz).

Archaeological excavations carried out at the end of the 19th century in the Andernach-Neuwied area found remains of piles in the Rhine (their analysis in the 20th century showed that they had been felled in the middle of the 1st century BC), which may belong to Caesar's bridges , although its location has never been determined exactly.

As for the Ubios, in the year 39 B.C. Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa finally moved them to the west bank of the Rhine in payment for their loyalty over the years, as they had been demanding for some time, fearing reprisals from neighboring tribes. They remained loyal to Rome throughout their history, eventually mixing with the Franks who created new kingdoms in Gaul during the Middle Ages.