The Witches of Thessaly It is not the title of a literary work or a film, but the generic denomination given in Ancient Greece to the women who lived in that region between the 3rd and 1st centuries BC, due to their presumed common ability to calculate the date of eclipses. of the moon with amazing precision. In reality, it was a generalization of someone who truly knew how to predict these phenomena:the Thessalian Aglaonice, who has been immortalized by authors such as Plato or Plutarch and today is honored by baptizing a crater on Venus with her name.

The etymology of this name suggests that it is a nickname, since in Greek it is the conjunction of the terms aglaòs (luminous) and nike (victory), jointly translatable as victory of light . An expression with magical resonances that underlines the supernatural character that was attributed to their knowledge, explainable because in the Hellenic civilization, so extremely patriarchal, women had a secondary role:they lacked citizenship and, therefore, the right to participate in life. politics; she depended on a kúrios (guardian, whether father, husband or relative); and she was educated expressly for marriage and procreation, developing most of her life in the gynaeceum (part of the house exclusively for women).

At least, that was the female condition in Athens, which is the place best known for the abundance of sources and that is extrapolated to the rest of Greece without being sure that it was like that everywhere (we know that in Sparta, at least, was different, with greater equality). But, from what is inferred from the written references, it seems that at least in Thessaly it must have been similar, since it was assumed that its astronomers resorted to supernatural arts and had a close relationship with Hecate, a primitive, polymorphic divinity, originally from Anatolia and protector of the home but also of sorcery, ghosts and necromancy.

Therefore, Aglaonice was identified as a priestess of the Hekatic cult and, as such, she received from the goddess the ability to make the sun and moon turn on or off at her will. These characteristics gave her a negative image that led her to appear in some version of the Orpheus myth, as responsible for the death of her wife Eurydice by secretly loving her (she died bitten by a viper when she was fleeing from Aristeo, a lesser god). Obviously, her true virtue was knowing how to calculate eclipses with total precision. How could she do it?

Probably thanks to a trip that she would have made to Mesopotamia with the permission of her father, Hegetor of Thessaly. There, between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, in the territory between what is now Iraq and northeast Syria, the first civilizations were born and the most advanced knowledge of astronomy was developed, especially in the southern part, where Chaldea, better known like Babylon (although the first was rather a region of it). And that's where the Neo-Babylonian astronomers calculated the saros.

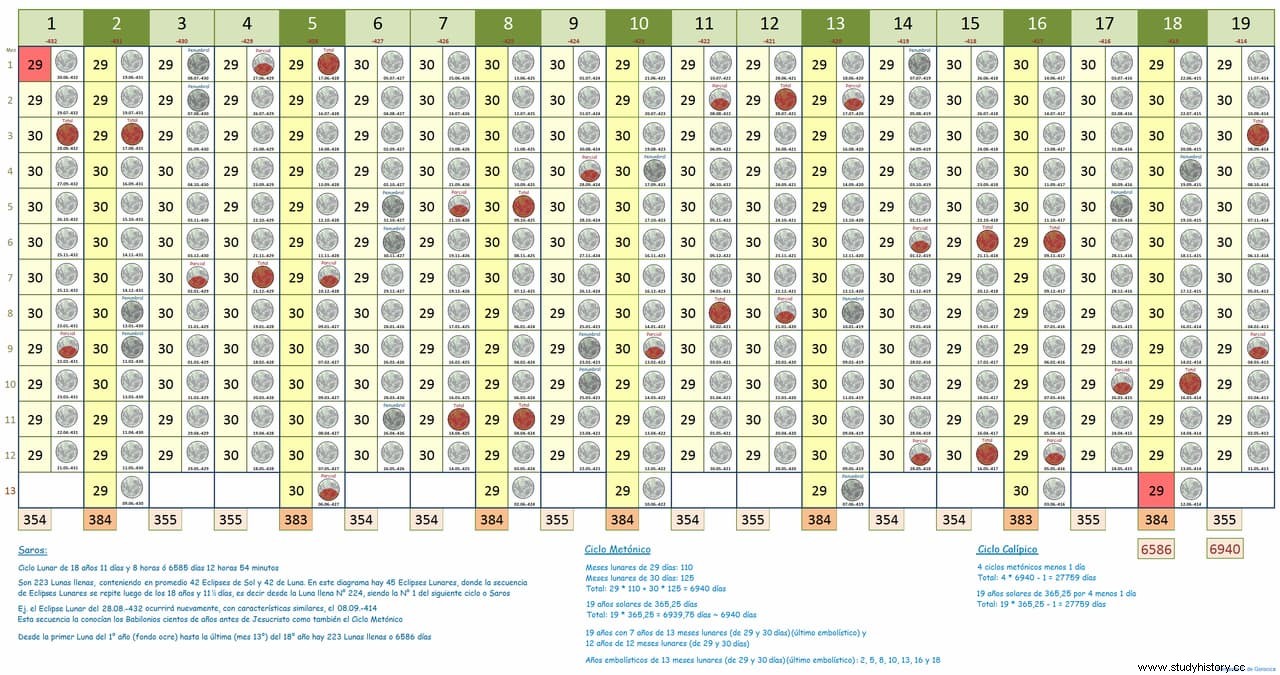

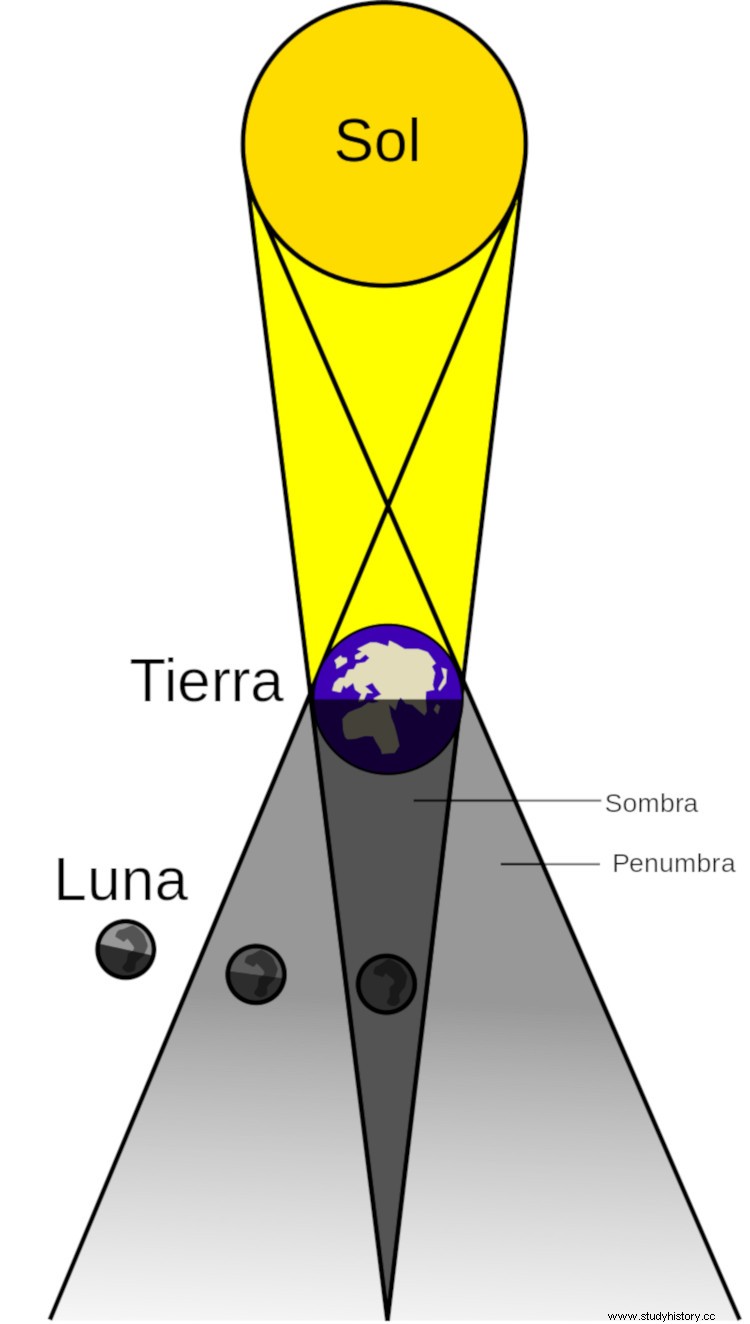

The saros were the lunar cycles established by the Chaldean Berosus (who lived between 350 and 270 BC), after discovering that each one lasted 6,585.32 days, that is, 18 years, 11 days and 8 hours, coinciding in each cycle. three periodicities related to the lunar orbit:the synodic month (from one new moon to the next), draconic (mean interval between two successive transits of the moon through the same node) and anomalous (longest stretch of the lunar elliptical orbit) . Each cycle of saros contained 84 eclipses, of which half were of the sun and half of the moon. The Babylonian sages wrote down the cycles on clay tablets, and Aglaonice must have returned with some; she must have learned to read cuneiform writing - which would be an indication that her journey was real - and she only had to look at the dates.

For most people, however, it was mere witchcraft that she used to swindle them and thus passed to posterity, as the Greco-Roman Plutarch would reflect a century later in the chapter Duties of marriage of his work Moralia :

In fact, Aglaonice's ability to predict was extended to Thessalian women in general, as if they all had it by nature. Other classical authors echoed this. In his work The clouds , Aristophanes says: «If, buying a sorceress from Thessaly, she would bring Selene down at night…» For her part of it, in her Meleager , Sosiphanes puts it:"Everyone says that any maiden of Thessaly makes her [the moon] disappear with magic songs and, therefore, Selene's descent from the sky is misleading" .

Even Plato dedicated a few lines to the subject in Gorgias, putting in the mouth of Socrates:«But we must fear, dear friend, that it does not happen to us, what is said happens to the women of Thessaly when they make the Moon descend (...)» . Virgil in his Eclogues and Apollonius of Rhodes in his Argonautics They also reviewed the subject, always in the same sense. In a context as misogynistic as the Greek, that a woman could equal or surpass men in wisdom -or in skill- could only be explained by resorting to sorcery, hence a popular saying became common:«As the moon obeys Aglaonice» .