The stereotype of the tyrannical king, capricious and insensitive to the suffering of the people is true to a certain extent and almost always in times after the origin of that institution, when it was the guarantor of the survival of his people. A good example could be the Chinese Shāng Tāng, who even distributed money among his subjects to lift them out of poverty.

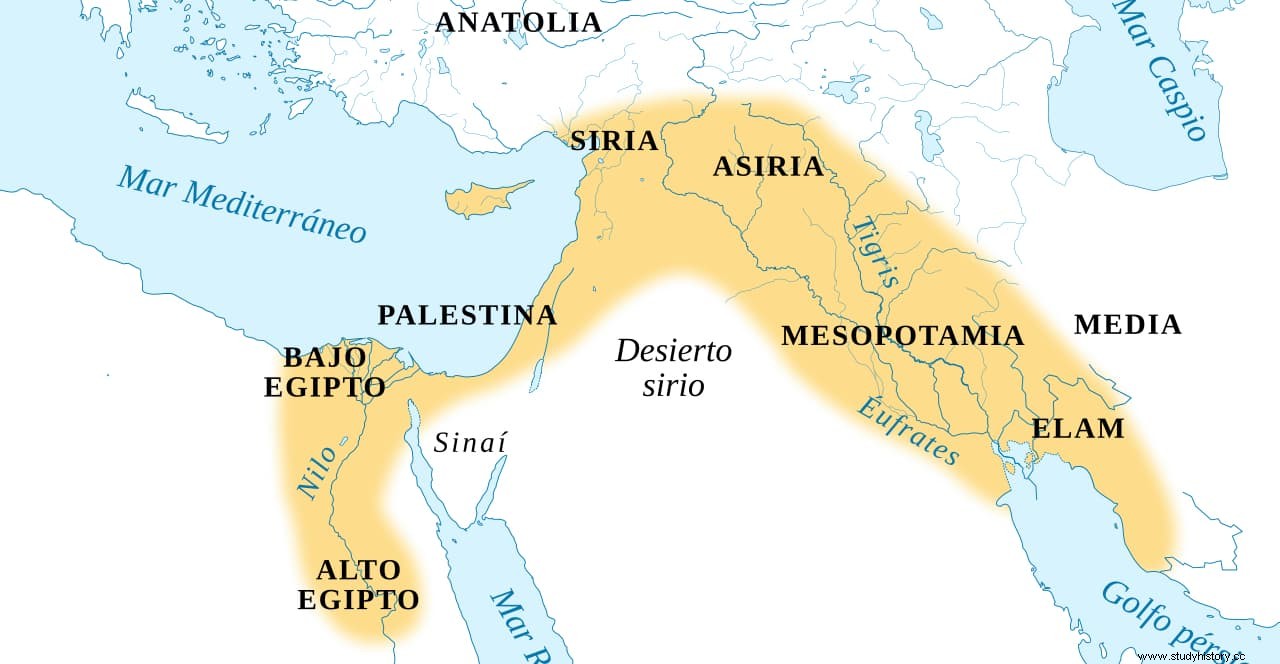

The monarchy is not a medieval institution as is often said -in fact, in the Middle Ages it suffered a crisis due to feudalism- but it has its origin in Antiquity, in the first historical societies, with a very clear function:to exercise a protective role over the community, both defensively and in terms of guaranteeing the grain supply, hence the king had absolute power to exercise command of the army and distributed grain from his warehouses in lean periods. The case of the agrarian empires of the Fertile Crescent is paradigmatic:let us remember the silos that the pharaoh and the Egyptian clergy possessed for this purpose and other similar ones in Mesopotamia.

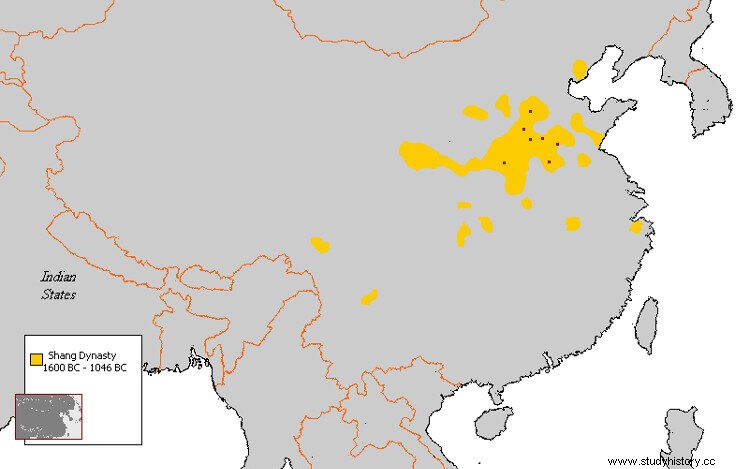

It is always difficult to determine exactly the moment in which the history of a country or territory begins and that is why the periodizations are a mere indication. Taking as a reference the element that is used to consider it, the appearance of written documents, China would have made the leap from Prehistory about five thousand years ago, when the first attempts at proto-writing are dated. But since there is no unanimity to seriously consider these attempts, the usual thing is to place that beginning in the Shang dynasty.

Shang means trade and the word is used because that dynasty grew closely linked to that activity, the result of a great advance in agriculture. Actually it wasn't the first, because before there was another, the Xia; but of this one, which would have lasted from the 21st century B.C. to the XVI a. C. and is associated with the beginning of the Bronze Age, there is no information until much later times nor does it present a proven archaeological record, so its seventeen kings have a rather legendary character. Thus, it is considered that the Shang, their successors, were the ones who put China in history.

In reality, there were also doubts about the historicity of the Shang, since the documentary sources were all several centuries later, from the Zhou period, and there was no archaeological evidence either. It was not until the 20th century that the latter began to be excavated around the Yellow River to prove that the Zhou texts were telling the truth. Specifically, oracular bones (bones with writing), bronze objects and plastrons (tortoise shells with inscriptions) were found, to which were later added the archaeological sites of the Erligang Culture (near Zhengzhou, in Henan) and the city of Yin (which was the capital of the Shang in 1350 BC).

The Chinese broke into the Neolithic around the beginning of the third millennium BC; they did it thanks to the cultivation of rice, just as in the aforementioned Fertile Crescent wheat was the driving force and in America corn. That stage coincided with the Xia dynasty, whose last ruler was called Jié. Chronicles say he was a tyrant, corrupted by the influence of his favorite concubine, Mo Xi, who is described as depraved, sadistic, and immoral; His wickedness is even illustrated with the legend of the lake of wine that he ordered to be made and then forced three thousand of his subjects to dry it out by drinking, most of them drowning drunk.

In this way, Jié was losing popular sympathy, something that he himself aggravated by forcing his subjects to collaborate in the construction of a lavish palace. The coffers of the state were squandered on his megalomaniac work and, incidentally, the people became poorer by having to neglect their fields. As the power of his dynasty had been weakening before, he would be the last and weakest link; bad thing if on top of that his capricious behavior had everyone irritated.

It is then that the figure of Shang Tang appears, whom we mentioned at the beginning. Born around 1675 BC, he was of noble birth, from a family that had served the court of Shang for several generations, one of the lordships under the suzerainty of King Jie. When he married the daughter of Prince Xīn, he entered the government, where he did a good job for seventeen years and managed to make Shang increase in importance compared to other vassal territories of the king.

Shang Tang perceived the suffering of the people and became aware that a radical change was necessary, which obviously involved the overthrow of Jié and his hated concubine. Thus, he began to establish contacts with the various lordships of the kingdom and attracted the support of forty of them. Although he stated that he was not in favor of the chaos that this type of movement usually causes, at the same time he interpreted the opportunity presented to him to lead the opposition from his privileged position as a divine mandate, thanks to which, by the way, he knew that the military commanders they were also fed up with Jié.

Tang also had the advantage of having placed a trusted man at court:Yi Yin, a servant of his wife who had risen through his wisdom and so impressed the king that he made him a minister. The first insurrectionary step was prudent. The Shang lordship stopped paying royal tribute to raise funds and publicly distance themselves from the monarch. He did not react thanks to Yi Yin intervening dissuading him. But the following year, Tang again refused to pay, and Jié could no longer remain idle.

Perhaps everything obeyed a plan but the case that Tang was arrested while he was visiting a temple and locked in the Xia Tower, thus becoming a martyr and example for all. So much so that the other lordships rebelled and the military leadership refused to mobilize to quell the revolt. The king had no choice but to release him... to see Tang openly lead the insurrection. All this happened midway between the twenty-second and twenty-third years of Jié's reign.

The Tang conquered several major cities, expanding his domain and attracting more and more supporters. China, which to be exact did not yet exist as such, was involved in a civil war for several years until in the thirty-first year of the reign both armies met in Mingtiao (present-day Anyi) to fight the decisive battle. Helped by a strong storm that disorganized the enemy plus the detachment of his own men, who were indolent in combat, Jié was defeated and had to flee.

He initially took refuge in Sanzong but the Tang soldiers chased him there and he had to resume his escape from it until they captured him in Jiǎomén. The king was overthrown and sent into exile on the Nánzhào mountain, where he would later die. One of the historical sources, the Shiji (Historical Memoirs, by Sima Qian), tells that Jié very expressly summed up his fall by placing the reason in not having executed Tang at the time. The fact is that the Xia dynasty ended, giving way to another that would reach thirty sovereigns until 1046 BC, when it would have to give way to the Zhou.

But meanwhile, Tang was the first of the Shang dynasty, which has gone down in history as the protagonist of what is considered to be the first aristocratic revolution in China. The memory he left behind was good, despite the fact that he was also a pioneer in establishing a state organized in the feudal style and with an important pillar in slavery, since he reduced to that condition all those who continued to resist change:after definitively defeating them he deprived them of their liberty and sent them to work in the fields as forced labor. It was probably a necessary measure, given the harsh situation in the country after that long internal war.

In fact, it took five years to get things back on track. Most of the Chinese families had lost members and the fields were semi-abandoned which, combined with a fatal period of drought, led to misery and famine. Aware that he could not lose popular support, Tang then promoted an unprecedented shock measure:he ordered his mints to mint extra runs of gold coins that were later to be distributed among the most disadvantaged classes so that they could not only face their shortage but also buy back their children.

Buying back children is not a metaphorical expression. When subsistence crises came, many peasants were forced to sell their children to guarantee the survival of the children (the buyers took care of them) and their own (fewer mouths to feed). The enormous dimensions of the country and the strong vegetative rate of its population made this a custom that would be repeated throughout history, along with getting rid of newborns for the benefit of men.

In any case, the image of state officials distributing coins must have been unusual. At a later time, with a more developed economy, the measure would have been catastrophic due to the effect it would have on prices and fiduciary value. But we are talking about Protohistory, the beginning of the Ancient Era of China, coinciding with the Bronze Age. Everything was too primitive to have a significant negative impact and the peasants received the initiative with evident satisfaction, of course.

That, together with the tax cuts that Tang decreed, the relaxation in military recruitment and the advanced agricultural technique that the Shang clan had promoted (which, deep down, was what led to the displacement of the Xia, whose fields yielded a lot less), favored economic development, also allowing many bordering states around the Yellow River to accept a vassalage relationship. The kingdom became rich, the new king established the capital in Anyang and did not rage against the memory of his predecessor, respecting his palace and erecting monuments in his honor. He would die around 1646 BC, after a reign of seventeen years.