If you remember, a few months ago we published an article dedicated to Quinto Fabio Máximo, five times Roman consul and dictator who was in charge of reading the declaration of war to Carthage and saved the capital of the Republic from its conquest by Hannibal, which is why which was nicknamed the Shield of Rome .

Well, in ancient times a shield was not much if it was not accompanied by a sword and that role fell to another pentaconsul, Marco Claudio Marcelo, who won some victories over the Carthaginian general and conquered Syracuse; that's why they called it the Sword of Rome .

As usual, not much is known about Marcelo's youth. Not even his date of birth, which is supposed to be before 268 B.C. based on the fact that, according to Plutarch, he was over sixty years old when he assumed his fifth and last consulship. The Romanized Greek historian recounts in the corresponding chapter of his Parallel Lives that since he was young he stood out in hand-to-hand combat, as a soldier, compared to other aspects of his training. He even saved the life of his brother Otacilio during a battle in which they were surrounded during the First Punic War, so it was clear what direction his professional future was going to take.

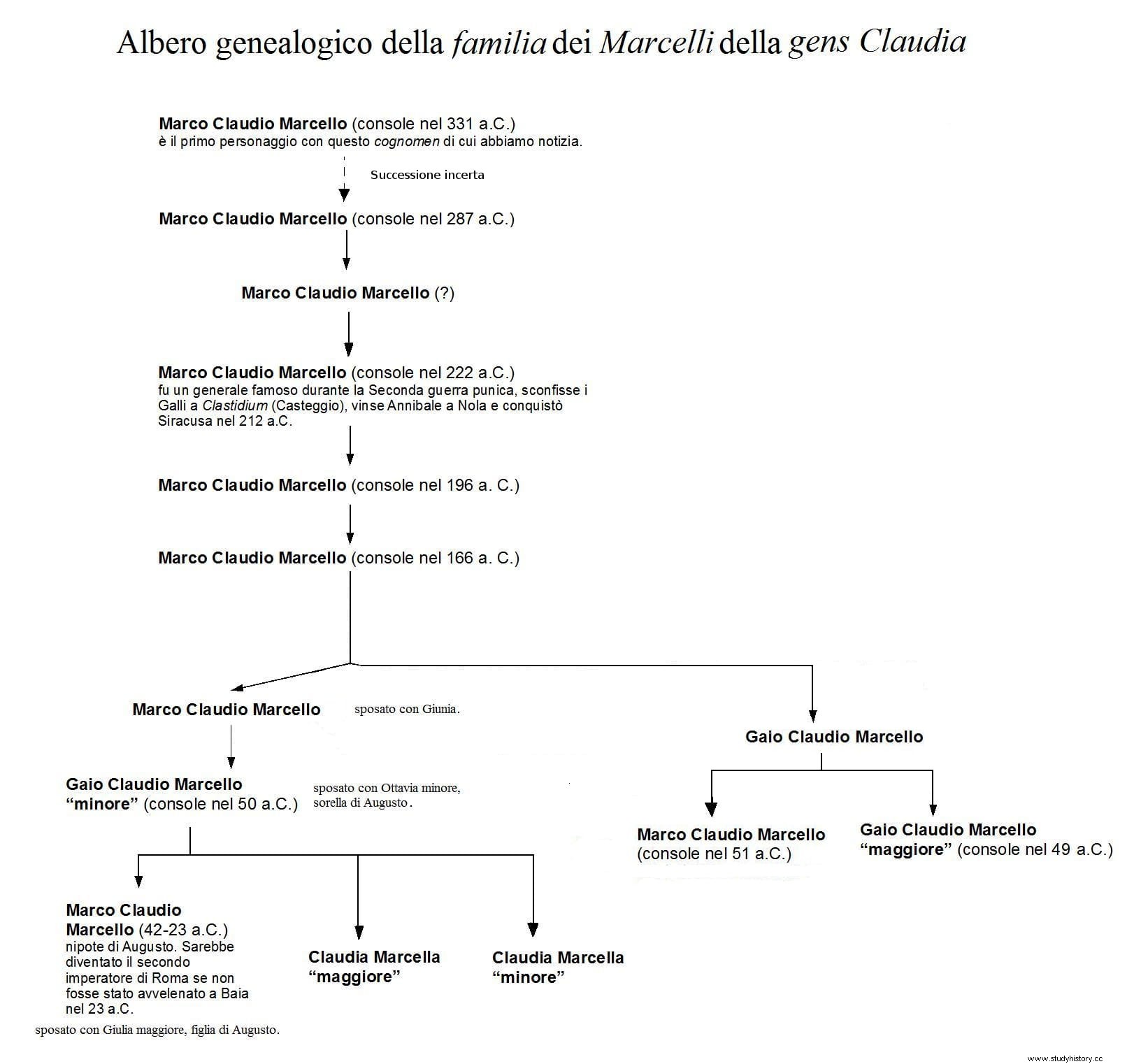

His superiors always praised him for his skill and courage, this reputation being what led him to his first public position, that of curule mayor, a kind of administrative official dependent on the urban praetor who constituted the first step of the cursus honorum and, therefore, he was also open to the plebeians and not only to the patricians. By the way, another Hellenic chronicler, Posidonius, reports that he was the first of his family to use the cognomen Marcelo, although there are sources that indicate that he was already present in his genealogy.

The election as curule mayor was in the year 226 BC, which confirms the late start of Marcelo's political career, perhaps the result of a certain lack of interest and his preference for the military world, only that in Ancient Rome both things were indissoluble . A confrontation against another mayor, Gaius Scantilio Capitolino, for having insulted his son Marco de el, ended in a lawsuit that he won, using the corresponding compensation to buy objects for the temples. It is possible that this noble attitude earned him a new political step that he received at that time, that of augur.

The augurs were priests for life under the orders of the pontifex maximus and whose mission was to interpret the will of the gods based on various signs and rituals, something fundamental in the life of the Romans, who did not take a step without first informing themselves about the omens. Like the previous magistracy, the commoners could carry it out from the year 300 B.C. thanks to the enactment of the Ogulnia Law (in fact, five of the augurs were required to come from the commons).

Therefore, Marcelo was already in his forties and it was around 222 B.C. when he skyrocketed his political career by being elected consul. Rome was on almost continuous alert, since the First Punic War had ended but now the Gauls were the enemy; not by their wish, since it was precisely Bolus and Insubrians who sent embassies requesting peace after decades of conflict and after the generals Publio Furio Filo and Gaius Flaminio had defeated them time and time again. However, Marcellus and his consular companion, Gnaeus Cornelius Scipio Calvo (brother of Publius and therefore uncle of the future Scipio the African ) were not interested in peace; after all, the prestige in his position was obtained with military triumphs.

So, Polybius says, they refused to parley and began a campaign across the Po and besieging the city of Acerrae. The Insubrians had asked the Gesets for help, who sent thirty thousand men, some of whom in turn surrounded Clastidium, a Roman settlement in Cispadana Gaul. Marcelo came to his aid with an important contingent of cavalry and crushed the enemy, defeating his chief Viridomarus in single combat. He then met with Scipio, liberated Acerrimae and conquered Mediolanum (present-day Milan), now in Cisalpine Gaul.

The insubrios surrendered unconditionally and Marcelo -only he- was rewarded with what he was looking for:a triumph , which was also accompanied by the spolia opima , that is, the weapons and equipment taken from an enemy, which was considered the most prized trophy; after a parade to the Capitol, the honoree hung that panoply from an oak tree next to the temple of Jupiter Feretrio, the oldest in Rome. Only Rómulo and Aulo Cornelio Coso had previously won a spolia opima and no one did it again, so Marcelo entered history through the front door.

The following five years must have been relatively quiet for him because Plutarch did not report anything special until 216 BC, when he was named praetor. The reason was compelling:two years earlier the Second Punic War had broken out and in June 217 B.C. Hannibal shattered the forces of the consul Gaius Flaminius Nepos at the Battle of Lake Trasimeno, just as he had done six months earlier at Trebia with another Roman army. The Carthaginian general thus became a serious danger that was confirmed the following summer, when he again caused a disaster in Cannae.

Marcelo, initially assigned to Sicily, received the pretura (which empowered him to impart justice as well as to take military command) to defend Rome. For this he formed an army with his troops plus the survivors of Cannae (to whom he thus gave the opportunity to compensate for his dishonor), marching towards Campania to meet the adversary. This one, trying to achieve the adherence of the Italic peoples, had already obtained that of Capua and was preparing to enter Nola when the local patricians raised the alarm.

Marcellus hastened to the scene and repelled the Carthaginians in a minor but highly morale-raising skirmish. At least for a while, as Hannibal got his revenge with another win at Casilino. Thus came the year 215 B.C. and Marcelo had to appear in the capital at the request of the dictator Marco Junio Pera and his magister equm Tiberius Gracchus, who confirmed him in his position and also named him proconsul. In fact, he accumulated more powers, since the consul Lucius Postumius Albinus died shortly after in Cisalpine Gaul at the hands of the skittles (who would use his skull as a drinking vessel) and the people chose Marcellus as his substitute.

Quite a problem because he was not a patrician, something inadmissible for the Senate, so Marcellus was forced to resign and focus on operations in Campania. There he again prevented the conquest of Nola by Hannibal, this time so forcefully that the Numidian and Hispanic cavalry auxiliaries went over to his side; then he got Casilino back. These successes gave him such popularity that in 214 he was elected consul again, and this time no one could oppose him, unusual as he was. Together with his companion, Quinto Fabio Máximo, they were the Shield and the Sword , as we said at the beginning, and nicknames were good for them:the first, in effect, acted as a shield, defensive, prudent and apparently passive, in favor of slowly wearing down the enemy (he was also nicknamed Cunctator , something like Timer, "he who delays"); the second, dynamic, always looking for confrontation like a gladius .

And the Sword he continued to act victoriously in preventing a third Carthaginian attempt to conquer Nola, after which he was able to recover the plan to go to Sicily; it was important because Syracuse, once friendly to the Romans, was now in the hands of the Punic generals Epicides and Hippocrates. Marcelo got the people to banish them and the Romans entered the city while Marcelo personally took Leontino (current Lentini), where the two fled had taken refuge. The harshness with which the vanquished were treated prompted half of Sicily to turn against Rome and Syracuse to rebel, but it was useless.

Marcelo laid siege to the city (in whose defense he distinguished himself with the inventions of the famous Archimedes) while he developed a pacification campaign for the rest of the island. It took two years for the legions to prevail but in the end they did, partly based on the fear they caused by massacring those who resisted, as in Enna. Also essential for this was the final fall of Syracuse between 212 and 211 BC, weakened by an epidemic and the defection of Hispanic mercenaries; Archimedes, by the way, died at the hands of a legionnaire, something Marcelo regretted.

The consul tarnished his victory with the harsh looting to which he subjected the city, which contrasted with the left hand displayed by his companion Quinto Fabio Máximo in Taranto. Now, he must not have cared much, since he had other concerns; including concluding the campaign by defeating the other Carthaginian armies and seizing Agrigento.

But that left him in the hands of his subordinate Marco Cornelio Dolabella because he resigned his position and went to Rome hoping to receive another triumph that, however, he was denied; he had to settle for one watt (ovation, a minor modality in which he made the parade on foot instead of in a chariot, with a crown of myrtle instead of laurel and without accompaniment neither of his troops nor of the Senate), although the loot he exhibited was so rich that it looked almost the same.

He later collaborated in the fight against the Carthaginians in Hispania, a period during which he was elected consul for the fourth time with Marco Valerio Levino as his partner. Here his inflexible behavior in Sicily exploded in his hands, which his political opponents reproached him for based on the wave of complaints that a delegation of island cities manifested before the Senate. To smooth things over, Marcellus ceded the government of the island to Levinus and he resumed command of the army against Hannibal, who had once again defeated the Romans in Herdonia.

Both sides clashed in Numistro, remaining at a table but with the Carthaginians stumbling around the Italian peninsula without a clear objective while Marcelo, who took control of the Apulia region, followed in his footsteps but was unable to engage in the decisive battle that wanted. This prevented him from going to Rome for the elections, from which Quinto Fabio Máximo and Quinto Fulvio Flaco were elected consuls. However, he retained his position as proconsul and in 209 B.C. he met Hannibal at Canusius. Here, too, there was no actual battle, but rather a succession of skirmishes with no results other than heavy losses on both sides.

Hannibal went to Taranto to try to break the siege to which Máximo subjected it but failed. At the same time, Marcelo was questioned about the casualties harvested; he defended himself so convincingly that the following year he was elected consul for the fifth time. It would be the final chapter of his inexhaustible biography because the following year, after putting down an uprising of the Aretians (an Etruscan people), he set out again in search of Hannibal and after discovering his camp he went on a mission to reconnoitre the terrain and was surprised by a Numidian patrol; a lance finished him off and days later his fellow consulate Quincio Capitolino Crispino followed him because of the wounds received from him.

It should be added that Hannibal, upon learning of him, went to personally see the body of his enemy to pay him honors, organizing a high-class funeral for him. Not only that, but he sent the ashes to his son in a gold and silver urn. Some sources (Cornelio Nepote, Sexto Aurelio Víctor and Valerio Máximo) say that they never reached their destination because some bandits stole them along the way, while others (Plutarch) assure that they did. It was the end of the Sword of Rome .