«And since the Persians had suffered years before a great shipwreck when going to double the cape of Athos, they also began, about three years before the present expedition, to arrange the passage through said mountain, practicing in the following way:They had their galleys at Eleunte, a city of the Chersonesus, and from there they summoned soldiers from all nations, and forced them with whip in hand to open a canal; one succeeded the other in the work, and the neighboring towns of Mount Athos also entered the part of the fatigue».

This is how Herodotus begins to tell, in his work The Nine Books of History, the beginning of one of the most important military engineering works of Antiquity:the excavation of the so-called Xerxes Canal, also known as the Acanthe Pit, a narrow passage floodplain that had to cross the isthmus of the peninsula of Mount Athos, in the Greek region of Chalcidice, to avoid the detour that its fleet would have to take and, thus, not expose it to adverse weather.

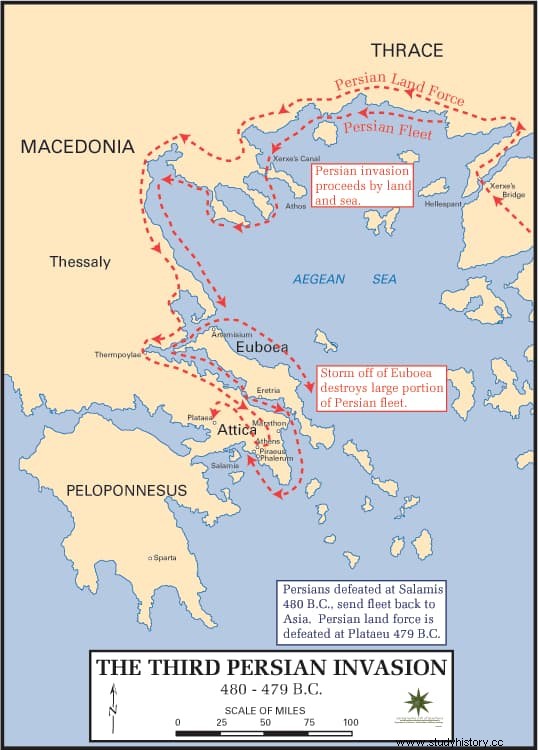

The Persian king, who had it started in 480 BC, did not do this on a whim. He was well aware of what had happened to his brother-in-law -and his cousin- Mardonius in 492 BC, during the First Persian War, when he commanded the formidable invasion fleet assembled by Darius I the Great. Made up of some three hundred ships and around twenty thousand men, with this force it was intended to go on the counterattack, after repressing the Ionian Revolt that the tyrant of Miletus, Aristagoras, promoted seven years earlier.

The Ionians, the Greeks of Asia Minor, were crushed by the Persians, who took advantage of their ancient internal division to prevail at sea in the Battle of Lade. Then Darío decided to extend the operations to Hellenic soil because of his support for the rebellion. First several Aegean islands fell into their hands (Chios, Lesbos, Tenedos, Thassos) and then the ships continued to take over the Chalcidic coast while the army occupied Macedonia, a land rich in gold, and reached the Danube.

It was then that nature turned against the invader:when he was sailing off the aforementioned peninsula to pass it to the south, a violent storm swept over the fleet, breaking it up, sinking many units and forcing them to return, so that the Persian king had to put an end to his plans. In reality there would still be a second naval campaign, which was no longer commanded by Mardonius but by generals Datis and Artaphernes, but with less ambitious objectives:to conquer Naxos and thus control the Aegean; they were successful, although they failed on the ground when they were defeated in Marathon.

The fact is that Darius's successor, his son Xerxes, was the one who took over at the death of his father in 486 B.C. The army that he assembled for it over four years was vastly larger, and consequently he also needed a larger fleet to transport him; Herodotus speaks of one million seven hundred thousand men (plus auxiliaries) and other authors double or even triple the number, although current historians lower that number to less than two hundred and fifty thousand.

A huge figure, however, that he required more than four thousand ships, of which twelve hundred were triremes and three thousand galleys, including fifty penteconteros (ships of fifty oarsmen). Of course, not all of them were Persians; there were representatives of almost all the peoples under his control, from Medes to Indians, through Parthians, Cilicians, Assyrians, Phoenicians, Bactrians, Phrygians, Egyptians, Bithynians, Arabs, Ethiopians, Libyans, etc.

Now, Xerxes was not about to repeat his father's mistake by exposing the fleet to the elements. Therefore, while he was still making preparations, he ordered a canal to be dug that would avoid having to go around the peninsula of Mount Athos; In this he did imitate Darius, who ended the attempt by the pharaohs of the Egyptian New Kingdom to open a colossal canal (two hundred and ten kilometers) in the Nile Delta that would connect the Mediterranean with the Red Sea. Herodotus tells that the direction of the work was entrusted to two notables called Bubares and Artaquees. The mountain juts out into the sea and thus forms a massive tongue of land that, however, narrows to form an isthmus between the current towns of Nea Roda and Tripiti.

The canal was to cross two kilometers and be thirty meters wide by three deep, enough to allow two triremes to pass simultaneously. A pharaonic company that, according to Herodotus, had something of a megalomaniac: «When I stop to think about this channel, I find that Xerxes had it opened to show off and display his greatness, wanting to manifest his power and leave him a monument» . It took the Persians three years to have it ready, using for it recruited workers by force plus others brought from Egypt and Phoenicia that were distributed by nations.

First, the channel was traced with ropes, then the stone began to be broken in turns and the earth was excavated in baskets that were passed from hand to hand from the bottom to the edges by means of ladders. At each end a dam was built to work dry. Herodotus reviews the complex supply and supply network that it was necessary to set up in order to feed all those people, among whom the Phoenicians had the leading voice due to their skill, not only in that work but in the others, since it was necessary to build several bridges.

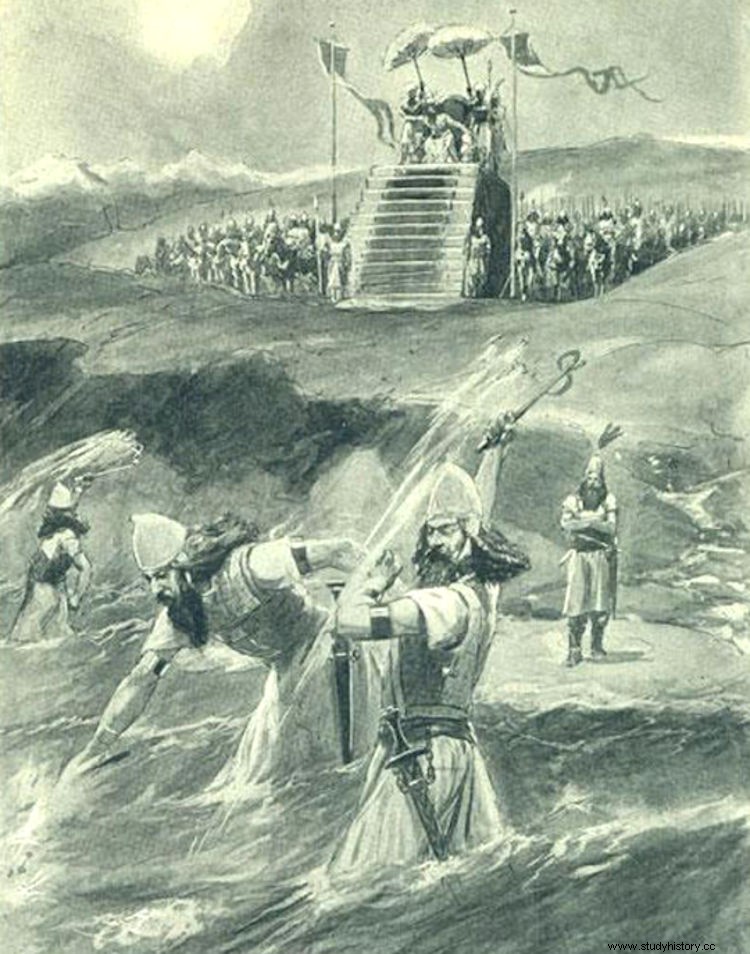

In fact, one of the best-known episodes of that war was the double pontoon formed with boats that Xerxes ordered to be laid over the Hellespont so that his troops could cross it, with that very special moment of the storm that broke it up and that the sovereign avenged by sending whipping the sea… and beheading the engineers. A bad omen that the augurs solved by interpreting a darkening of the sun -perhaps an eclipse- as a sign of victory (the sun king "was the forecaster of the Greeks and the moon the prophetess of the Persians" , according to Herodotus).

Xerxes wept with emotion as he watched his immense fleet from a promontory, identifying himself with Zeus and beginning the march towards Greece. However, while in Acanto, another bad news arrived:the death of Artaquees, one of those responsible for opening the canal, to whom he gave a funeral full of honors. Then he divided his army and one part continued by land with him in front while the other went by sea. Let us quote Herodotus again:«The naval fleet, already separated from Xerxes, sailed through the channel opened in Athos, a channel that reaches the gulf in which are the cities of Asa, Pylorus, Singo and Santa. Having taken on board the people-at-arms, he from there continued his route towards the Sound of Termeus. So he doubled the Ampelo, promontory of Torona, and was collecting the galleys and troops from the Greek cities where he passed... »

The historicity of the Xerxes Canal was questioned for a long time. This was due to the fact that, although it was part of the landscape around Athos for a century, it was never used again after the passage of the Persian fleet, so it progressively deteriorated and was covered with sediment. Thucydides mentions it in his History of the Peloponnesian War, written around 400 BC, and Demetrius of Scepsis did the same in the 2nd century BC.

It was necessary to wait for the techniques of modern Archeology to demonstrate their existence through aerial photography, as well as by the geological analyzes on the ground that were being carried out by the Frenchman Choiseul-Gouffier in the 18th century, the Englishman T. Spratt in 1838 and the German A. Struck in 1901. Even so, in 1990 its dimensions were still not clear, nor if it functioned as a canal or simply as a drag strip for ships, as happened in the diolkos that crossed the Isthmus of Corinth.

It was the following year when a team of Greek and British geophysicists confirmed, by analyzing the sediments and other techniques, that the Xerxes Canal crossed the peninsula from one side to the other and, therefore, that Herodotus was not lying. His remains today constitute what is one of the few Persian monuments in European territory.

Fonts

The nine books of history (Herodotus of Halicarnassus)/History of the Peloponnesian War (Thucydides)/Xerxes (Jacob Abbott)/The emperor and the rivers. Religion, engineering and politics in the Roman Empire (Santiago Montero Herrero)/Wikipedia