Visiting the British Museum is something like entering a time machine that transports you chronologically and geographically to those times and places in the history of the world that you dream of since you studied them or saw them in a book.

The tour of the museum can take whole days if you want to see it calmly and in its entirety, which is why many tend to choose to focus on a few chosen pieces such as the friezes and metopes of the Parthenon, the Rosetta Stone, the Egyptian mummies, the Nineveh bas-reliefs and Nimrud, the turquoise Aztec snake or the Easter Island moai, among others.

For me, the Royal Game of Ur should also not be missing in that selection.

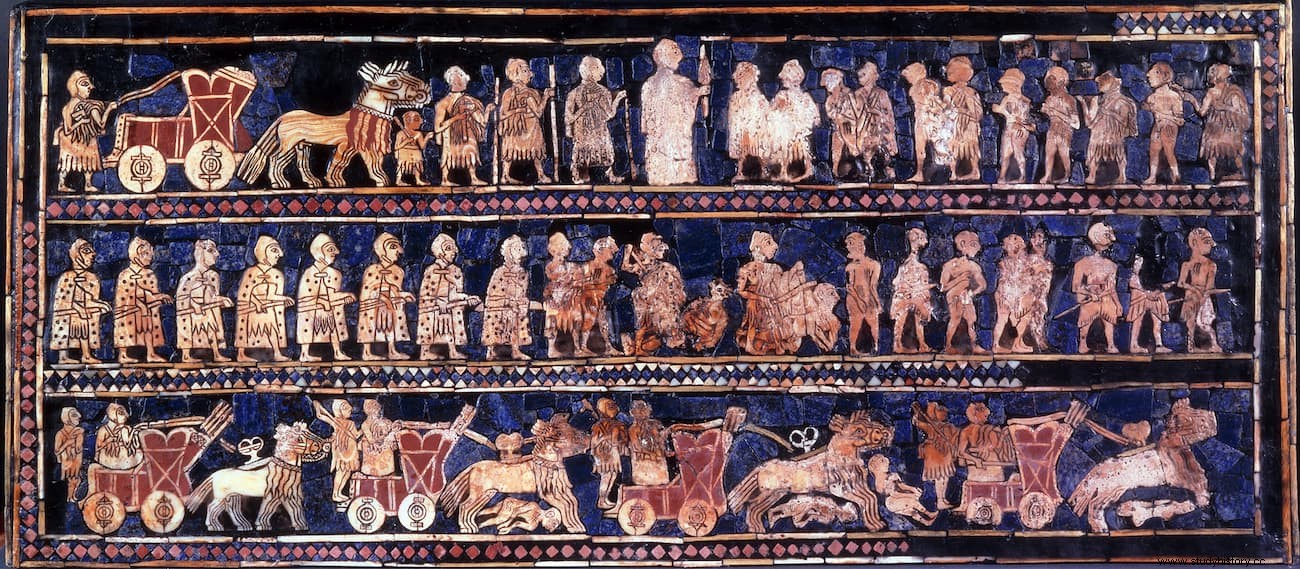

In fact, not only the game but also the so-called Banner, a kind of wooden box whose panels are made with that beautiful technique that is inlay (similar to mosaic but instead of using only tesserae, ivory, wood and various metals, seashells, mother-of-pearl, coral...) and show military and domestic scenes. Its special interest lies in the fact that, as its name indicates, it is from the Sumerian period and is dated around the 26th century BC.

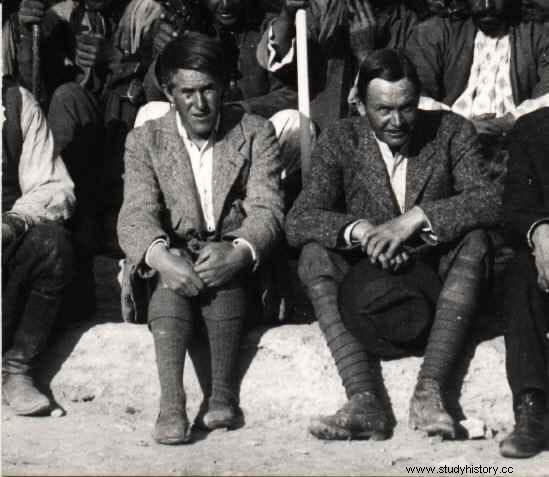

It was found in 1927 by the famous British archaeologist Sir Charles Leonard Wooley, when he was conducting an excavation campaign in the Necropolis of Ur, south of present-day Baghdad (Iraq). In that place he unearthed sixteen tombs (although the total of those located exceeded two and a half thousand) that he baptized with the name of the Royal Tombs of Ur, built in brick and with a vaulted ceiling, all corresponding to the Archaic Dynastic period and with their deceased occupants. accompanied by sacrificial servitude ad hoc , in addition to the corresponding funeral trousseau.

That of the Akkadian queen Puabi (considered by some not a sovereign but a priestess) was magnificent. Along with her, five armed guards and ten maids died or were killed, as well as a pair of oxen with the cart they were pulling, which shows the opulence of that character. It was in his tomb that precious things appeared, such as a spectacular headdress, a gold cup that was still in his hand, several splendid jewels and, above all, two precious lyres (one of which is in the British) and a harp.

Puabi's was not the only tomb with an identified occupant; also that of Meskalamdug, of which it is not clear if it was lugal (king) or only ensi (ruler, half administrator, half priest, no blue blood) or that of A-kala-dug. In any case, the others also provided a good collection of objects, such as the gold helmet of the first.

We have already seen the case of the Standard, found in one where seventy-four bodies lay, but there were others and from two of them two separate boards with tokens from the Royal Game of Ur were extracted, which are estimated to be about four thousand five hundred years old. .

Despite this, it is not the oldest known board game because the senet Egyptian is almost a millennium earlier and the oware , a type of mancala (board game with tiles) originating in West Africa, also predates it. However, the three have similarities in their development, keeping resemblance to Parcheesi:the objective is to remove the pieces from the board before the rival following a few squares, for this reason it is also similar to backgammon, although it is believed that it derives rather from the Roman tabula.

Some are of the opinion that the senet , despite being older than the asseb , which is what the Egyptians called the game of Ur, would actually be a version of it; Until more information is found about it, it is impossible to know. What is obvious is the resemblance, which we know despite the fact that the rules of neither of them are preserved.

In the case of the senet It has been necessary to do quite an arduous reconstruction work because it must have been so popular that no one bothered to leave an explanation, even elementary. The board was divided into three parallel rows of ten squares each that had to be traversed with a number of checkers (between ten and twenty, there were probably variants) depending on what came out on some boards, being able to form barriers and eat those of the adversary, in a curious combination of parcheesi and goose.

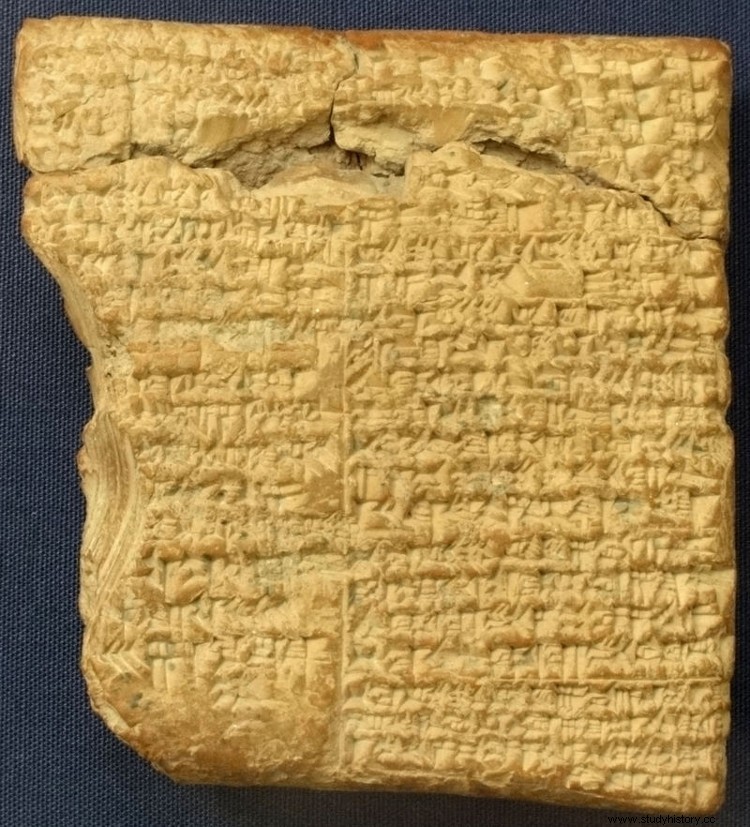

We do not have a regulation of Sumerian either, but there is a basic description on a tablet with Babylonian cuneiform writing, quite late, signed by a scribe named Itti-Marduk-Balāṭu between 177 and 176 BC.

It can be deduced from it that, as in the Egyptian case, it was based on the mutual pursuit of the pieces of two players:each one had seven, one black and the other white, which had to complete a tour of the twenty squares on the board (divided into two groups of twelve and six respectively joined by two others) following what three pyramidal dice indicated.

As in the senet , you could eat the opponent's chips and send them to the exit according to what the drawing of each box indicated; and, as in the other, whoever first removed their pieces from the board won.

Of course, there was an important difference between the Egyptian game and the Royal Game of Ur:the first was very popular, we said before, played by all social strata, while the Sumerian seems to be played exclusively by the wealthy classes and only has been found associated with them, either in the aforementioned tombs, or sgraffito on the walls of the palace of the Assyrian king Sargon II in Dur Sharrukin (current Khorsabad, Iraq), or in the trousseau of Tutankhamun himself.

Today any enthusiast of Mesopotamian culture or plain History can find reproductions and practice, although the funniest thing is that there are even versions available to play an online game. and mobile apps.