If some Gallic leaders thought they could take advantage of the intervention To shake off the German threat out of hand, they quickly became aware that they had been trying to fight fire with fire. According to The Gallic Wars , panegyric with which Caesar justifies and extols his conquest campaign, among some communities an alliance against Rome began to be forged, especially among those who inhabited the northernmost part of the three into which Gaul was divided, the Belgium . The Belgian peoples, renowned for their bravery, swore an oath and exchanged hostages to seal their pact, determined to stand up to the Romans. Although the ambitious proconsul justified his aggression with the threat that this coalition could pose, it seems clear that the germ of it is, on the contrary, the threat of an imminent Roman campaign in Belgium . The fact that Caesar commissioned the Senones, neighbors to the Belgian territory, to keep him abreast of what was happening there indicates that he was already gathering information for his next offensive, materialized that same summer –57 BC. C.– when eight legions marched north. Caesar's campaign against the Belgians had begun.

Of those eight legions, six had fought during the previous year's campaign:the VII, the VIII, the IX and the X were veteran legions (to better understand the structure and formation of these legions Desperta Ferro Especial VIII:The Roman Legion (II) in the Lower Republic), while the XI and XII had been recruited by Caesar in the Cisalpina at the beginning of 58 a. C., without the required senatorial authorization. Two other legions, the XIII and XIV, were raised in the winter of 58-57 BC. C., which is another indication about the intentions of the proconsul.

The Belgians

Belgian communities occupied the space between the Sequana –Seine– and the Rhenus –Rhine– , without this last river being a clear border between Gauls and Germans, since we also find Germanic towns on its left bank. In fact, the Belgians themselves said that "[...] they came from the Germans and that a long time ago, after crossing the Rhine, they had settled there due to the fertility of the territory, expelling the Gauls who lived in these places" (Beautiful Gallico , II.4). We know, however, that the Belgians are of Celtic lineage due to their onomastics and customs, although that origin beyond the Rhine would be true, since during the 3rd century BC. C. they arrive in Belgium groups of Danubian Celts, hatching a culture with particular features, among which the predominant role of war stands out. We thus find warrior sanctuaries such as Gournay-sur-Aronde or Ribemont-sur-Ancre, in which panoplies, faunal remains and human remains are deposited as a founding act of the community and the delimitation of its space.

Value and military potential are key in the self-affirmation of the identity of each Belgian community –the Bellovaci, for example, were reputed “for their valor and prestige” (BG , II.4) and as "a people with a reputation for being very brave in Gaul" (BG , VII.59)– and also in that Belgian supra-ethnicity that César recognizes. The Belgians thus boasted of having been “[…] the only ones who, in the time of our fathers, when all Gaul was subjected to havoc, prevented the Teutons and Cimbri from entering their lands.” (BG , II.4). Belgian it has been tentatively interpreted as “the greatest”, and in the etymological analysis of the ethnonym we find the root *bel- , "bright, resplendent", related to the warrior divinity Belenos. Whether it is a self-assigned ethnonym or one imposed by neighboring peoples, its warlike connotation seems evident, something that is also common to many names of Gallic or Germanic peoples.

But the Belgian peoples were not a monolithic unit, but among them there would have been different levels of cultural development, largely related to their greater or lesser insertion in the commercial circuits that , in an increasingly intense way, linked Gaul with the Mediterranean world. Thus, emos or suesiones, whose territory is located around the valley of the Axona –Aisne–, seem to have been articulated in a more centralized way, with oppida fortified that are absent in the territory of other communities. Mediterranean imports, especially Italian wine –archaeologically materialized in the remains of amphorae– are also more abundant in its territory than in the rest of Belgium , where “merchants don't come very often” (BG , I.1).

The Gallic world is developing rapidly, with the appearance of already state formations, governed by magistracies, senates and assemblies , although the tension between the monarchical aspirations of some individuals and those aristocratic governments is manifest. We are going to witness a triple game:within each community there are tensions to seize political power; it can also be seen how there are regional struggles to occupy a preeminent place – for example, as we will see, in Belgium –; and the most powerful peoples of Gaul vied for supremacy, such as the Arverni and Sequani who supported Ariovistus against the Aedui allies of Rome. All this supported by networks of clientele, which can also be seen at various levels:between individuals from the same community, between the aristocracies of the different communities and even between different peoples. Both the internal struggles and the patronage network, in the end not very different from what exists in the Roman world, will serve Caesar in achieving his goals.

Caesar against the Belgae and the Battle of the Axona River

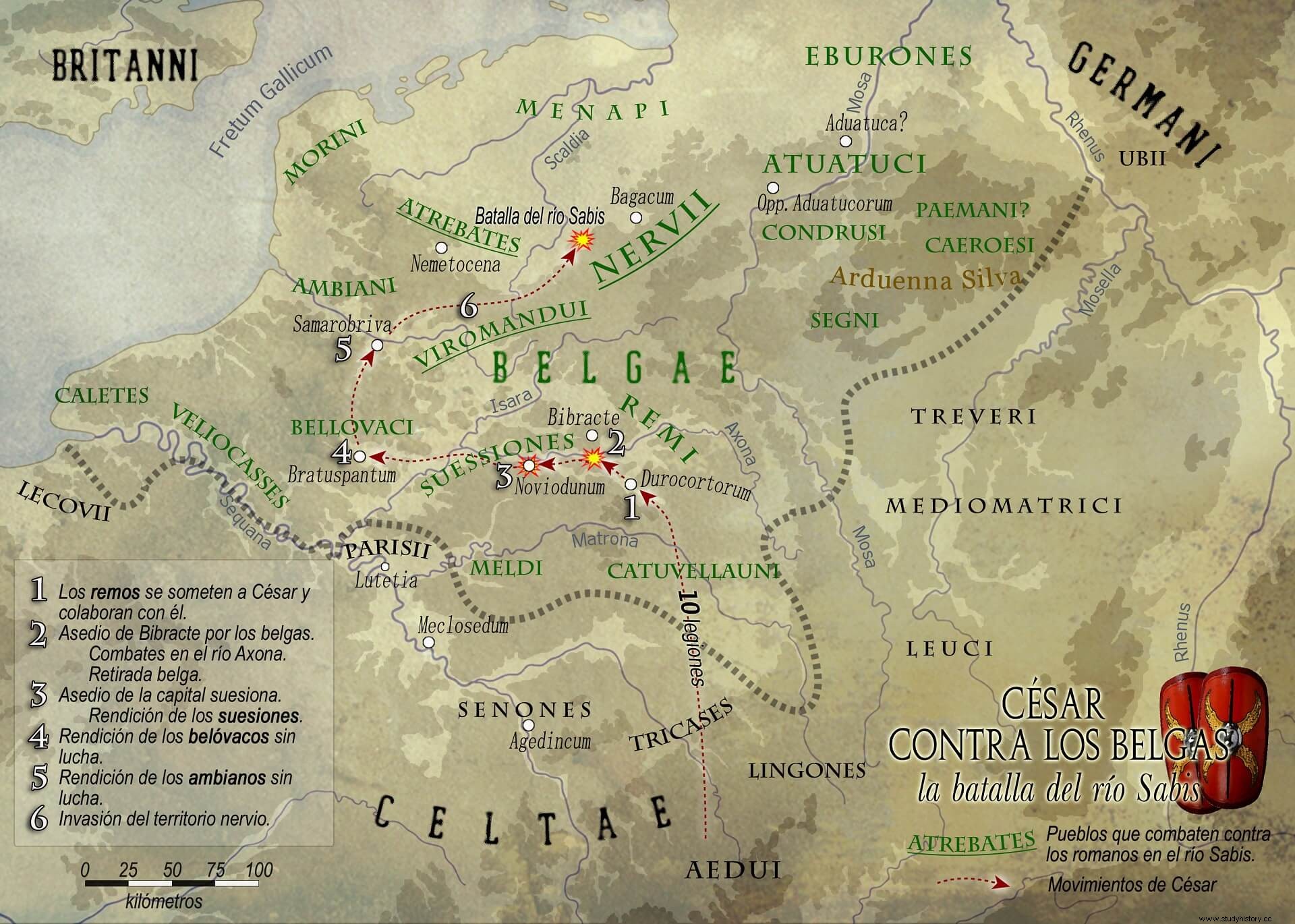

Well into spring, when there was fodder to feed the riding and pack animals, César left his barracks to present himself at the borders of the Belgium . There he received emissaries from the Remos, who declared that they were not part of the collation of the rest of the Belgians and offered their help to the Romans.

According to the oars, a general assembly had taken place of the Belgians in which each community had detailed the number of troops that it promised to contribute. Included in the coalition are Cisrenan Germanic peoples, such as the Chondrusi, Eburones, Cerosians, and Pemans, as well as the Atuátucos, descendants of those six thousand warriors who would have stood guard over the impedimenta during the Cimbri and Teuton migration two generations ago. The belovacos would contribute 60,000 men (out of a total capacity of 100,000); the Sueses, 50,000; the nerves, another 50,000; the Atrebates, 15,000; the Ambians, 10,000; the Morinos, 25,000; the Menapians, 9,000; the caletes, 10,000; veliocases and viromanduos, 10,000; the atuatucos, 19,000; and the Chondrusi, Eburons, Waxers, and Pemans, 40,000. The sum gives a total of 298,000 men in arms , which is a certainly high figure, which would correspond to a population of between one million and one and a half million inhabitants, taking ratios of 1:4 or 1:5 men of military age per inhabitant. For an approximate territory of 110,000 km² we would be talking about a population density of between 11 and 14 h//km², similar to what has been calculated for the whole of Gaul at the time. Belóvacos and successions disputed the direction of the war, which finally fell to the “king” Galba succession due to his abilities. The oars, who declare themselves "brothers [of the suesions] and of their same race" (BG , II.3), they go, instead, to support César to achieve regional pre-eminence. Their loyalty to Rome will not even waver during the subsequent Gallic rebellions, which will earn them that preponderance, becoming the main civitas gala, only below the eduos; your oppidum Durocortorum would eventually become the capital of the Roman province of Galia Belgica .

Caesar took the oars hostage – a common practice to ensure fidelity – and sent the druid Diviciacus, head of the pro-Roman faction among the Aedui, to devastate the Belovac territory, trying to thus subtract from the coalition its most powerful member. Furthermore, knowing that the Belgian army was at hand, he crossed the Axona and established his camp on the other side, leaving the legate Quintus Titurius Sabinus with six cohorts to garrison the bridge; by controlling the river he could ensure the arrival of supplies from the Remo territory. The excavations of Napoleon III located between the Axona and a small stream, the current Miette, on the Mauchamp hill the possible location of the Roman camp.

The Belgian army had moved against Bibracte, oppidum remote some 8,000 paces from the Roman camp, devastating the surrounding villages and fields. The attack against Bibracte gives us an idea of the limited development of polyorcetics among the Gauls: attempts were made to clear the wall of defenders by a hail of projectiles, to approach in a testudo and try to open a breach in the wall or set fire to the gates. The square barely withstood the onslaught, and at nightfall he sent an emissary through the enemy lines to beg Caesar for help. This sent part of his auxiliaries, Numidian and Cretan archers and Balearic slingers who, taking advantage of the night, managed to enter Bibracte. This reinforcement complicated the Belgian bombardment of the walls, now repelled by the darts and glans of the auxiliaries, which, together with the threat of being taken over in their rear, decided the indigenous coalition army to lift the siege and go against the roman camp. Less than two thousand paces from the latter they established theirs, and the Roman general can realize the enormous size of the enemy troops when he contemplates, according to the fires lit by them, that the extension of the Belgian camp was more than eight thousand steps.

Probably the Belgian army did not reach the figures given by the oars, although, without a doubt, it would be superior to the Roman . Those 298,000 men had to respond to the maximum mobilization capacity of the Belgian communities – although it seems that the Belovaci could contribute even more – which would include every man with the right to bear arms. However, given the supply and coordination problems that this figure would entail, not all would have been mobilized. Among the Belgian troops, the retinues of the aristocrats, professional warriors, would stand out, although the vast majority would be men dedicated to other tasks, mostly peasants, but capable of wielding a spear if the situation required it.

In any case Caesar was aware of his numerical inferiority and waited to engage in battle. For a few days he sounded out the Belgians with battles between his cavalry – fundamentally Gallic auxiliaries, among them the Treveri, neighbors of the Belgians – and the enemy, taking the opportunity to build cross-cutting ditches on both sides of the hill where he set up his camp, reinforced with forts equipped with of artillery. As he did against the Helvetii or as he would later in Alesia, Caesar employed the extraordinary Roman engineering ability and the no less extraordinary capacity for work of the legionnaire to give himself a tactical advantage. He thus protected his flanks from a possible encircling movement, more than feasible given the size of the Belgian army. The proconsul knew, as generals like his uncle Mario's before him, that the dolabra it was as important as the gladius to win a battle.

This done, he presented a line of battle in front of his camp, leaving in it, as a reserve, the two fledgling legions, the XIII and the XIV. Some cavalry skirmishing ensued, but the Belgae did not budge, as to catch up with the Romans they had to traverse a small boggy area - presumably where the Miette brook now runs - and then attack uphill, which meant giving them a huge blow. opposite advantage. Instead, part of the Belgian troops tried to ford the Axona to attack the fort defended by Titurio and destroy the bridge, in order to cut off the Roman retreat and deprive them of supplies. But the proconsul reacted immediately and sent his cavalry, archers and slingers, who, moving quickly, caught the enemy still crossing the river and were able to repel him.

Logistics also wins wars, and the size of the Belgian army now played against them, as food became scarce , a problem that we see repeated often in the Gallic armies, which do not have a supply train like the Roman one. Added to this was the news that the Aedui were approaching Belovac territory, so they decided to return to defend their site. It was thus agreed “[…] that each one should return to his house and that they should gather from everywhere to defend the first ones into whose territory the Romans would lead their army” ( BG , II.11). This shows the lack of coordination in the command of the Belgian coalition, weighing more the interests of each community, something that was also verified in the way the withdrawal took place, almost a flight:at nightfall, each one got into march, without order or concert, alerting the Romans with the hubbub, who, moreover, had spies inside the enemy camp who told them what was happening. Still, Caesar, fearing an ambush and to avoid night combat, always confusing and complicated, waited until dawn to pursue him, once his scouts confirmed the enemy's withdrawal. The cavalry and the legate Tito Labienus with three legions overtook the Belgian rearguard, and great mortality was produced as the enemy broke ranks and each sought his salvation. Caesar had broken the Belgian coalition.

The submission of the Belgians

Without delay the Roman proconsul took advantage of the disbandment and, by forced marches, appeared that same day in front of the Suesian capital, Noviodunum. Despite having few defenders, he could not take it, thanks to its wide moat and high walls, with which he prepared to fortify his camp and prepare for the siege, building mantlets, towers and a ramp (see «The Roman camps from the 1st century to C." in Awake Ferro Special VIII:The Roman Legion (II) in the Lower Republic). Meanwhile, the bulk of the Suession army was able to enter the oppidum , but, demoralized by the Roman deployment and taking advantage of the intercession of the oars, they surrendered and handed over weapons and hostages.

His speed in making decisions and in his movements is another remarkable feature of César. Without delay, he set off towards the main belovaca square, Bratuspancio, but, before even reaching it, he received the surrender from him – deditio –. This time it was the druid Diviciaco who interceded for the Bellovaci, who had client ties with the Aedui – ties that, as we have seen, did not prevent them from attacking them at Caesar's request; the power of Rome outweighed the ancient alliances. Hostages and weapons were again taken, and the Roman army continued into Ambian territory, probably reaching their capital Samarobriva and also accepting their surrender.

But not all Belgians were going to give in so easily. To the northeast of the Ambian territory lived the nerves, who reproached the rest of the Belgians for their cowardice. Refractory to the influence of Rome, they did not consent to receive Mediterranean imports, especially wine, considering it debilitating –although these statements probably have more to do with the ethnographic discourse of Caesar, for whom greater distance from the Mediterranean means greater barbarism, than with the reality-. The Roman army advanced into Nervian territory, and on the third day Caesar learned from prisoners that the Nervians awaited him some 10,000 paces away, on the other side of the Sabis River. There has been a lot of discussion about which river Caesar is referring to, and different researchers have argued that it would be the Sambre, the Scheldt or the Selle. The identification with this last channel, following Turquin and Herbillon, seems to us the most accurate. Along with the nerves, the Atrebates and the Viromanduos had come, and the Atuatucos were also expected, on their way. The nerves had sheltered their non-combatants in an inaccessible place, between swamps, which indicates that an evacuation of the territory had taken place.

The road to the river was obstructed by hedges of brambles and branches that the nerves had built on purpose, to channel the attackers and prevent the deployment of the cavalry, weapon of the that these Belgians hardly used. We would be in front of an enclave that marks the southern border of the nerve territory, a crossing point for a protohistoric path that would connect with the Rhine, later continued by a Roman road and known from the High Middle Ages as Chaussée Brunehaut . There the nerves repelled any aggression against their territory, and there they also hoped to repel the Romans.

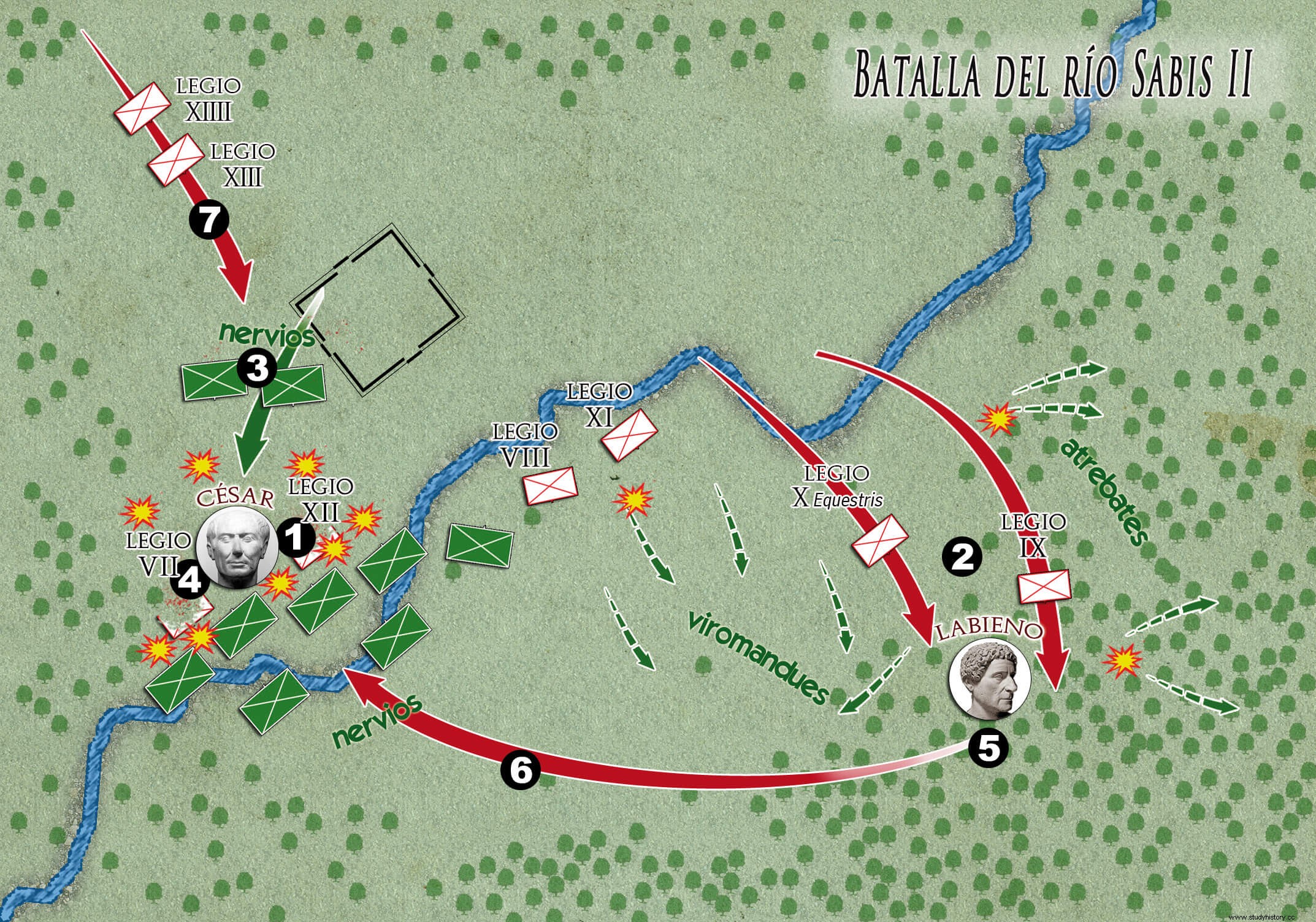

Caesar sent scouts and some centurions ahead of the army, to find a suitable location for the camp. They located a hill on the banks of the Sabis, which descended gently to the river, and in front of which, on the other side of the channel, another bank rose, uncovered in its first 300 m but then populated by a dense forest. Except for a few cavalry detachments patrolling the opposite bank, there was no sign of the nerves. Caesar sent his cavalry ahead and followed with the legions, but, given the foreseeable proximity of the enemy, he changed the usual order of march. Normally each legion marched followed by its impedimenta, but now Caesar ordered that six legions walk in the vanguard –first the X, followed by the IX, XI, VIII, XII and VII–, with all their impedimenta behind , and that the two inexperienced legions closed the rear. The nerves had been informed by some Gauls who accompanied the Roman army of its usual marching order, and they hoped, trusting also in the obstacles that hindered the Roman march, to be able to surprise and defeat the legion that opened it, without the The rest could come to their aid, blocked by the impedimenta of that one and the fences and brambles.

Cavalry, slingers and auxiliary archers crossed the river – about 1m deep – to drive off the Belgian cavalry and act as a screen while the legions built camp. Their good discipline is attested by the fact that they did not go into the forest to chase the enemy horsemen when they retreated. They did well:the enemy army hid in the thicket. The nerves, about 60,000 men, occupied the left flank; the Viromandus the center and the Atrebates the right wing –although The Gallic Wars does not give their numbers, we can estimate them at least 10,000 warriors each town based on what they had previously contributed to the coalition army.

The Battle of the Sabis River

The six legions reached the chosen hill and, After making the corresponding measurements, they got down to work. Except for the cavalry and the light infantry, it seems that Caesar did not have a line of legionnaires covering the work of his companions, as he had done, for example, when building a camp near the army of Ariovistus. It was an oversight that could have cost him dearly. At that moment the Roman impedimenta was arriving, a signal agreed by the nerves and their allies to begin their attack. It is doubtful that the Belgians had not already realized that what they faced was the bulk of the Roman army and not a single legion separated from the rest by their baggage, but, in any case, they decided to continue with their plan:they could still take the enemy. by surprise and with two legions still far from the battlefield.

The Belgae stormed out of the forest, easily repulsing the Roman cavalry and light infantry, and just as forcefully crossed the Sabis. César looked surprised and he immediately ordered the banner to be raised and the signals to be given with the tubas, to call to arms and attempt to form a line of battle. But, as the same proconsul acknowledges, decisive was the performance of the legates; each one had stayed with his legion while he built the fortification, and they knew how to react quickly and autonomously to try to repel the attack. Decisive was also the discipline of the legionnaires and centurions, who improvised combat groups wherever they were.

Caesar was able to ride up to Legion X's position on their left flank and deliver a brief harangue just as the Atrebates were within pilum . The legionnaires of the X and those of the IX, arrayed alongside those on the Roman wingtip, greeted them with a salvo of pila to their adversaries , who after crossing the river had to climb up the hill. This disorganized them, and the fierce charge of the legionnaires caused them to fall back, trying to stand up to the other side of the channel, although they were also dislodged from there. In the center, the XI and VIII legions had received the Viromandus equally and were fighting against them on the banks of the Sabis.

But things were different on the right wing. The head of the nerves, Boduognato, launched a part of his warriors, in close formation, against the XII and VII legions , while others tried to surround them from the right. They entered the half-built Roman camp and repulsed the scattered cavalry and light troops that had sought refuge there, as well as the calones , servants and slaves of the legionnaires. The Treverian auxiliary horsemen, seeing how the battle was developing, believed the Roman defeat to be complete and turned back. The XII legion fought huddled together, without space to conveniently handle their weapons, with many legionnaires abandoning the combat, with their signifer dead and the standard lost, and with most of the centurions wounded or killed. It was these tough, tough veterans who bore the brunt of the resistance, and it was probably their sacrifice that kept the Roman line from collapsing. Among them Caesar mentions the primus pilus Publius Sextius Crozier:"[...] one of the bravest, exhausted by his many serious wounds, to the point of not being able to stand up" ( BG , II.25). Caesar realized how dire the situation was and, snatching the shield from one of the legionnaires in the rear, he rushed to the front line, where he managed to inflame the spirits of his men and redouble their resistance, trying to open the gap between the maniples to be able to fight better. A precious pause was earned, in which the nerves had to recede to catch their breath before returning to the charge, and that Caesar took advantage of so that the XII legion approached the VII, which was just as hard, and so that the ranks of rearguard of both turned around to avoid the nerve attack from behind.

But what saved the day was the Providential arrival of the X legion against the Nervia rearguard. Having put the Atrebates to flight, Titus Labienus had led the X and IX legions to the Belgic camp on the hilltop across the Sabis, and, watching the battle unfold, ordered the X to descend. on the run to help his companions. In addition, the two legions that closed the Roman formation, the XIII and the XIV, arrived at the combat from the Roman rearguard, alerted by the flight of horsemen and servants, and launched themselves against the nerves. Trapped everywhere, they sold their lives dearly, suffering tremendous losses – according to Caesar only 500 of the 60,000 warriors survived.

The battle was over, and with it, practically, the Belgian resistance . César marched against the autátucos, who paid with captivity for trying to resist the Roman roller. Caesar commented thus:"Concluded these operations and thereby pacified all Gaul [...]" (BG , II.35). But Gaul was still far from being "pacified" and Caesar still had to use more than five years of campaigns to subdue it.