As is well known, the attack failed after that three battleships were put out of action by fire from the coastal batteries. This failure laid the foundations for the subsequent decision to execute the amphibious operation to land troops on the Galípoli peninsula. , carried out on April 25, which only managed, at the cost of enormous casualties, to secure a meager bridgehead on the shore. A second landing, carried out in August, would not be able to break the deadlock and finally, after numerous losses and in the face of enormous logistical problems, the beachheads would be evacuated between December 1915 and January 1916. Paradoxically, considering the confusion and failure associated with previous operations, these evacuations would be brilliantly planned and executed and set an example of Army-Navy cooperation.

The Dardanelles campaign originated from the Russian commander-in-chief's request for allied assistance to divert Turkish attention in the Caucasus, where Russian forces were under pressure; though, ironically, when the British and French began their attack in February 1915, the situation in the Caucasus had already been reversed and it was the Ottomans who were in retreat. The request came at a time when the British War Council was considering options beyond the Western Front, where it was assumed that no further offensives could take place until the arrival of the first New Army divisions in a few months. An attack on Cattaro (today Kotor), on the Montenegrin coast, was considered, which was considered to encourage the Italians to join the Allied cause. At the same time, there were proposals to land troops at Alexandretta (Iskenderun), near the current Turkish-Syrian border, which would provide a profitable naval base in the Levant from which to cut rail communications between Egypt and Mesopotamia, and likewise, a landing at Thessaloniki was considered, where an allied force would finally be established in October 1915.

The Dardanelles were chosen in part over the other options because they offered a higher prize since, if successful, they could threaten Constantinople , the capital, and precipitate the fall of the Ottoman regime or force it to sue for peace, as well as separating European Turkey from Anatolia and isolating Ottoman forces in Thrace, which could push Greece and Bulgaria to join the Allied cause and thus provide the necessary contingents to expel the Turks from Europe and open a route to support beleaguered Serbia. Furthermore, if the straits were opened, Russia could once again use that route to trade grain for much-needed weapons and finance, which it sorely lacked. Ultimately, the Dardanelles operation was expected to divert troops from other fronts and help the Russians in the Caucasus and the British in Egypt and Mesopotamia. Another key reason why the Dardanelles were chosen was that success could be achieved, they argued, with antiquated ships and without committing too many troops.

Initial hopes that the Greeks would join the allies and contribute troops to support a joint operation proved unfounded. In the absence of significant numbers of British or French ground troops that he knew were unlikely to be available, Winston Churchill, First Lord of the Admiralty –government minister responsible for the Royal Navy – advocated the option of a purely naval attack. On January 13 he managed to secure the consent of the War Council that "the Admiralty should prepare for a naval expedition in February to bombard and seize the Gallipoli peninsula with Constantinople as its objective." To support this option, Churchill obtained a report from the British commander in the Dardanelles, Vice Admiral Sackville Carden, suggesting that such an attack could be successful if executed methodically.

It is noteworthy that Admiral John Fisher, First Sea Lord – a professional Navy officer – was willing to support an action in the Dardanelles but was opposed to the idea of a joint naval attack without troop support. Admittedly, Navy opinion, both in the UK and in France, seemed to be skeptical as to the chances of success. Even a century later it remains unclear how a navy could "take" a peninsula without the support of ground troops. Unfortunately for the Allies, Lord Kitchener, the British Secretary of State for War, consistently opposed allowing significant numbers of troops to be provided for this operation. Of all the members of the War Council, he was perhaps the most vehement in his conviction that the Navy could win single-handedly, and therefore refused until March 10, when it was too late to be of utility in the attack, to be sent to the 29th Division, the last remaining professional type of the pre-war Army. Those soldiers, who could have overcome the defenseless beaches at the end of February, were forced to storm them in April under heavy fire. Thus, the navy would be forced to defeat an opponent on the ground with the exclusive support of its Royal Marines detachments. and naval landing parties.

The War Council approved the naval attack on February 28 at a meeting in which politicians were excited about the potential fruits of victory and the first Sea Lord had to being persuaded not to resign in protest, giving rise to one of the remarkable features of this affair:the planning of a large naval operation with the opposition of the professional Navy officer.

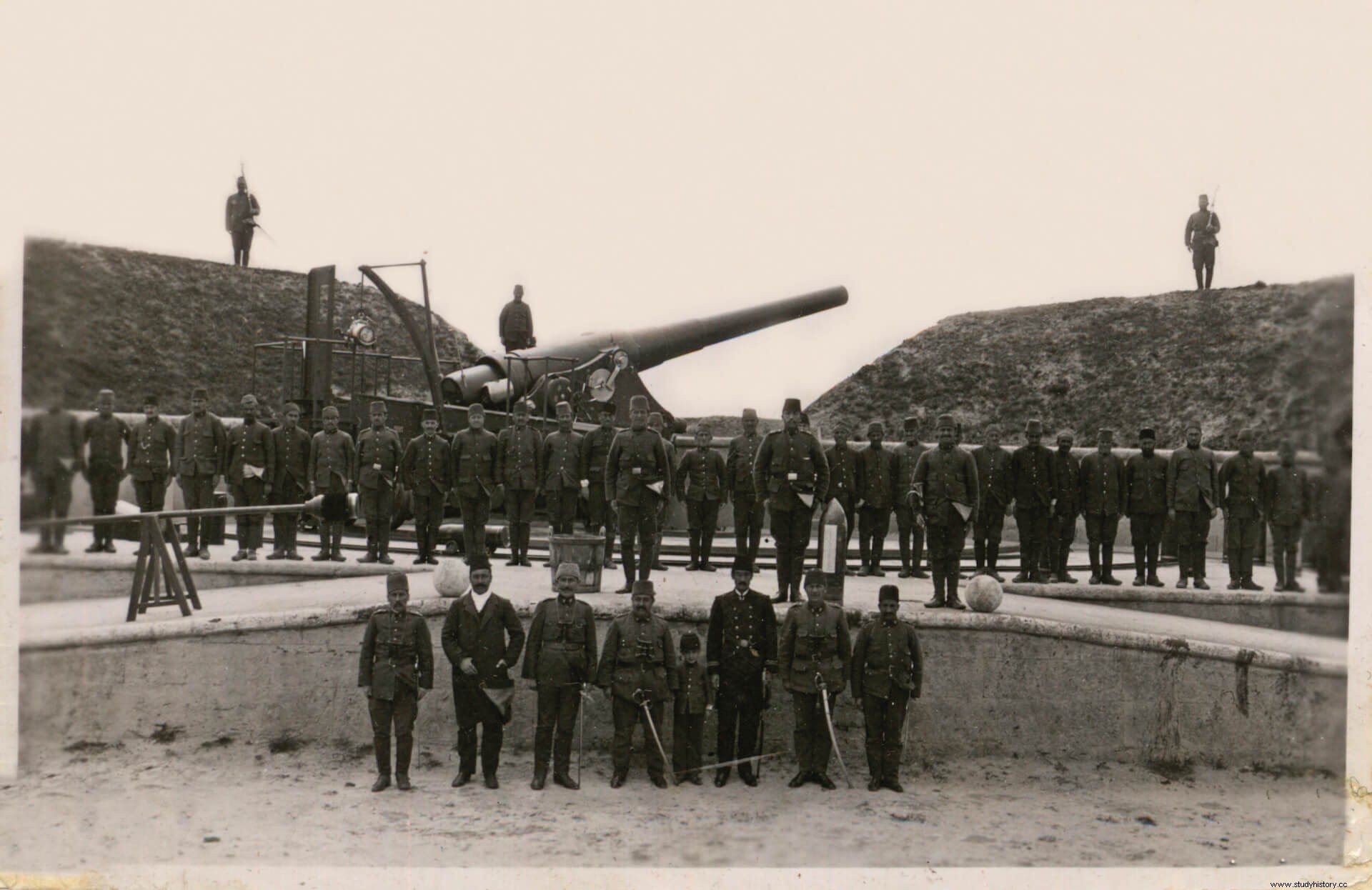

The defenses of the Dardanelles

The Dardanelles Strait, which connects the Aegean Sea with that of Marmara and, behind it, with Constantinople and the Bosphorus, is around 60 km long and varies in width from 6 km to only 1.2 km in the strategic Narrows , near Canakkale. The entrance to the strait was protected by outer forts equipped with a total of 17 heavy and 10 medium-range guns, installed behind ancient stone walls; inside was an intermediate defense made up of medium caliber guns located in four forts on the Asian side and one on the European side; and upstream, in the Narrows , were the fortresses of Kilid Bahr (in Europe) and Çanakkale (in Asia), with a total of 88 cannons of different calibers, between 14”, 11” and 9.4” pieces. In addition, to block the access of enemy ships, more than 300 mines had been distributed throughout the bay, in ten lines, covered by searchlights, and the defenses were reinforced with the arrival of 8 batteries, of four pieces each, of howitzers. 6" mobiles, capable of supplying indirect fire against any attempt to use minesweepers.

In a report on those defenses written in 1912 and published the following year in the Journal of the Royal Artillery , a British officer remarked rather presciently that “if these batteries are well manned and efficiently managed, it seems almost impossible for any ship to cross safely between two fires and also avoid mines and get through barricades”. The Italian Navy had bombarded the outer forts in 1912 and executed a night raid with fast torpedo boats without suffering significant casualties but, despite the generous expenditure of medals and promotions among those involved, that short, limited and covert raid into the straits offered few relevant lessons in 1915 for the allies and had only encouraged the Turks to devote greater attention to the defense of this waterway. Similarly, a bombardment of the outer forts by French and British ships on November 3, 1914, before the Dardanelles offensive had been conceived, had no significant consequences beyond prompting the Turks to reinforce their defenses.

Admiral Carden recognized that it was not possible to rush into the strait, but felt that a more methodical strategy might yield better results and planned one accordingly. In addition to the modern battleship superdreadnought HMS Queen Elizabeth, armed with powerful 15” guns, and the war cruiser HMS Inflexible, the fleet under his command also had 12 British battleships –of which 8 were scheduled for scrapping– and 4 French, prior to the dreadnoughts , less impressive and more expendable than the first two, being too old and slow to be of use in the North Sea. However, it was considered that they still carried some useful 10” and 12” guns, so they could also be used for important tasks and, if lost, it would not matter too much. Carden also had the support of several cruisers and destroyers, a seaplane carrier –HMS Ark Royal–, 6 British and 4 French submarines and more than 20 trawlers converted into minesweepers. The latter were underpowered and slow, a significant constraint given the strong current in the strait.

The bombardment of the outer forts It began on February 19, with calm seas, but bad weather meant that the attack could not continue the following day and it was not resumed until the 25th. To destroy the guns on land, direct hits were necessary, which was difficult. at long range with the skimmer guns of battleships; however, it was possible to subdue the forts from beyond the range of the shore guns, and once achieved, the battleships could close in to finish the job. In this way, by the end of the day the forts had been silenced and on February 26 the landing groups of sailors and marines reached the shore to complete the destruction work with explosive charges. The pieces were eliminated and a party of marines advanced to the town of Krithia, before the arrival of Turkish reinforcements forced them to withdraw on March 4.

With the outer defenses nullified, Carden could now focus on those inside the strait. The bombardment of the interior forts began on 26 February, when forts and battleships exchanged fire without inflicting critical damage on each other, as many of the Turkish guns lacked sufficient penetration to penetrate the heavy armor of a battleship and the ships did their best to destroy rather than contain. long-distance coastal defenses. Eager to try something different, HMS Queen Elizabeth bombarded the forts from the rear, across the Gallipoli Peninsula, with her long-range guns, but lack of precision limited her effects. What the fleet would have really needed were observers on the coast to direct the fire, or airplanes capable of correcting the lack of hits on the target, which unfortunately was not possible despite attempts to use the aircraft of HMS Ark Royal as observers. aerial.

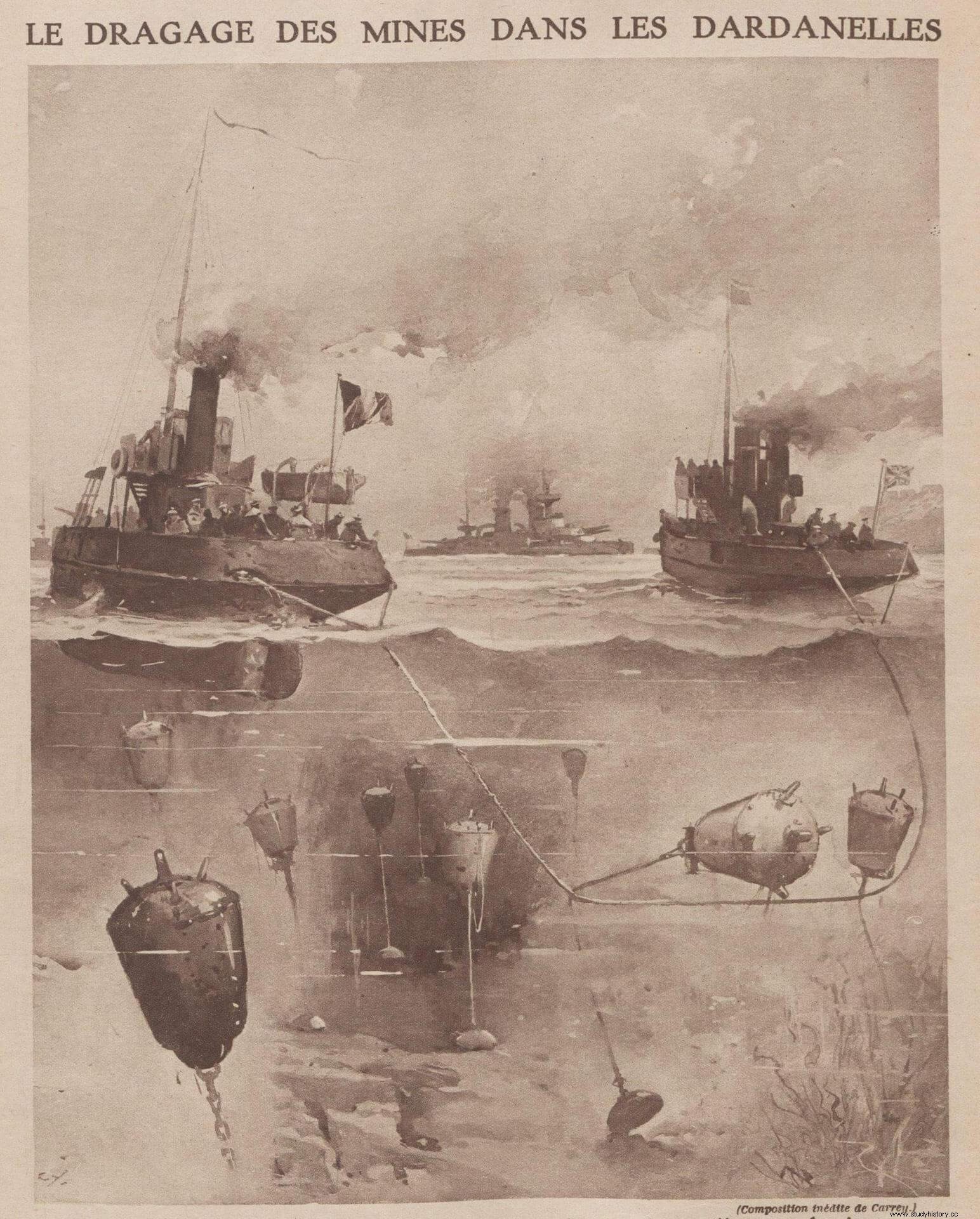

But the worst part is that the Turkish mobile howitzers remained hidden and virtually invulnerable to naval fire and, when detected, simply moved to another position. The shells they fired could not seriously threaten battleships, but they were a serious hazard to the unarmored minesweepers, which were needed to clear the belts of mines that prevented battleships from approaching within range of the forts and advancing beyond. of the Narrows .

The minesweeper trawlers were not fit for the task at hand; they lacked sufficient power and could only develop two or three knots against the current, making them easy targets for shore batteries and mobile howitzers. To dredge downstream they would have had to navigate the entire strait in a hail of fire before turning and dredging, so they were unsuitable for their task. They were flown by their peacetime crews, understandably daunted by the fire, although they were later aided by naval volunteers who tried to bolster their morale to little avail. Attempts to limit the risks by dredging at night also failed, as the Turkish searchlights could illuminate the target and a direct hit was necessary to put them and the guns they targeted out of action. Despite numerous attempts, the dredgers were unable to clear the mines, and after another failure on March 13, Carden opted to review his tactics. Until now his intention had been to clear the mines before the battleships silenced the shore batteries, but now he opted to have the warships destroy or contain the shore defenses to allow the minesweepers to do their job, although this was only possible during the day as ships needed visibility.

The decisive attack on the Dardanelles

The great daytime offensive It took place on March 18 and before the first shot was fired, the first casualty had already been claimed. The health of Admiral Carden, who had never been considered a suitable candidate to lead such an operation, had deteriorated significantly under the pressure and prior to the attack he became seriously ill and was replaced by his deputy, Vice Admiral John de Robeck. The plan of attack for the fleet was for the battleships to silence the heavy batteries of the Narrows with long-range fire and, once achieved, advance to the straits to engage the batteries protecting the minefields. With the batteries quieted, the minesweepers would be able to do their job and the battleships would be in a position to close in on the forts and, as they had done with the outer forts, destroy them at close range before entering the Sea of Marmara. For this, the large ships were distributed in three lines. The A line, with the modern superdreadnought HMS Queen Elizabeth and the war cruiser HMS Inflexible, accompanied by the two pre battleships –dreadnought more recent, the HMS Agamemnon and the HMS Lord Nelson, was to silence the forts at a long distance (12.8 km). Line B, with the British battleships Majestic and Swiftsure, and the French Gaulois, Charlemagne, Bouvet and Suffren, would advance beyond Line A once it had silenced the enemy guns to engage the Narrows forts at 7, 3 km away, with the support, behind it, of said line A. Line C, composed of 4 old British ships –Vengeance, Irresistible, Albion, and Ocean–, would remain in reserve and would be assigned to relieve line B at the right time.

The fleet entered the strait at 1030 hours and the A line was in position to open fire at 1100. At 11.50 the order was given to advance to line B and the French ships progressed towards the strait under a rain of fire . The battleships armor protected vital parts of her, but the Gaulois was hit by a 14” shell below the waterline, she was forced to retreat, and her captain ran her aground to prevent her from sinking. At 1400 hours the situation on the ground was becoming complicated; some guns had been put out of action, others had been knocked out of action or buried in rubble by the rain of fire, and some forts were running low on ammunition and their crews exhausted. At that moment, De Robeck ordered the C line to move forward but, as the B line ships turned to starboard to leave the action, an explosion rocked the second ship in line, the Bouvet, which promptly capsized and sank, without warning. that at first the cause was clear. The bombardment continued and by 1600 hours the heavy guns on the ground were mostly silenced but unfortunately the mobile howitzers continued to pose a threat and the minesweepers, which fled the strait without fulfilling their mission, proved inadequate. Worse still, shortly after 4 p.m., the war cruiser Inflexible struck a mine off the Asian shore and had to scramble away, narrowly avoiding sinking before managing to run aground on the Aegean island of Tenedos. The situation worsened when the Irresistible also struck a mine and began to drift towards the Asian shore and, to complete the disaster, the Ocean was disabled by another mine at around 7:00 p.m. Both Irresistible and Ocean were sunk that afternoon, and if that wasn't bad enough, the French battleship Suffren was rendered incapable of further offensive action due to damage sustained by fire from the shore. The positive is that casualties had been slight; Except for the 639 men from the Bouvet, almost all the others were rescued.

The cause of the serious losses of the day was a row of mines, laid parallel to the shore at Erin Keui Nay by the Ottoman miner Nurset on the night of March 8, which went from unnoticed until claiming its prey ten days later. Despite this, it was not immediately clear that the attack was over and de Robeck, buoyed by the news that reinforcements were on the way to make up for his losses, initially contemplated resuming the offensive. Roger Keyes, his chief of staff, was confident that a new attack would breach the defenses and worked tirelessly to build a more effective minesweeper force with converted destroyers, but he had no chance to prove his theory and remained convinced, until his death. death, that once it was ready – by April – it would have been successful.

At a meeting of Allied senior leadership on HMS Queen Elizabeth on March 22, De Robeck stated that he did not believe the fleet could make its way unaided, supported by this end by General Sir Ian Hamilton, commander of the land forces belatedly dispatched by Lord Kitchener. Therefore, the Navy accepted the defeat of March 18 and passed the baton to the Army, laying the groundwork for the even greater failure that was to come.

A century later there is still no consensus on whether a new attack could have been successful. The defenses in the Dardanelles consisted of an interconnected system of fixed guns, mobile batteries and minefields which, together, posed a greater challenge than they represented separately. The battleships proved capable of shutting down the forts, but were unable to get close enough to completely destroy them or break through the Narrows without the mines having been cleared. Unfortunately, the minesweepers were unable to make it under fire and the battleships could do little to silence the mobile batteries that covered them. The introduction of more effective minesweepers and crews trained to work under fire could have been the key to success. That's what Roger Keyes thought. Certainly the Turks had suffered greatly from the March 18 bombardment and were running out of ammunition for their heavy guns, but for their part the Ottoman and German commanders were confident that they could have defeated further attempts to clear the mines and, as the official British historian admitted after the war, "his confidence was probably justified."

More questions remain, such as what the fleet expected to do once it had forced its way into the Sea of Marmara. It was admitted that, even if the mines had been cleared and the fixed batteries destroyed, without an army to secure the ground on either side of the straits it would have been impossible to stop mobile battery fire on ships passing through the Narrows . Therefore, only armored ships would have been able to cover the journey and not supply or troop transports. The war fleet could have appeared before Constantinople and made a show, and perhaps even bombarded the city, but in the end it would have run out of fuel and ammunition, and if the Ottoman government did not collapse, the Allies would face the unappetizing prospect of having to fight your way back through the Narrows , just as Admiral Duckworth was forced to do in 1807, when another British fleet entered the Sea of Marmara without an army to meet an enemy unwilling to surrender.

The minutes of the momentous meetings of the War Council in London reveal the even more irresponsible assumption that the Turks would crumble if only the fleet crossed the Narrows , which seems to be based on little more than a wish. A more realistic assessment would have recognized from the outset the need for a sizeable joint campaign in which the Army and Navy could operate in concert to secure control of the strait and exert joint pressure on Constantinople. This had been the alternative advocated by the Navy at first. That the forerunner of the plans for an entirely naval offensive was Churchill, the political leader of the Navy, contrary to the opinion of Fisher, the professional leader, is one of the most remarkable facts of the operation and in these circumstances it does not owe us surprise the result.

Bibliography

- Corbett, Sir J. (1921):Naval Operations. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents, Vol. 2. London:Longmans.

- Forrest, M. (2012):The Defense of the Dardanelles. London:Pen and Sword.

- Keyes, Sir R. (1934):The Naval Memoirs of Admiral of the Fleet Sir Roger Keyes. I:The Narrow Seas to the Dardanelles, 1910-1915. London:Thornton &Butterworth.

- Marder, A. J. (2013):From the Dreadnought to Scapa Flow , Vol II. Barnsley:Pen and Sword. (1st edn, 1965)

- Massie, R. (2004):Castles of Steel. Britain, Germany and the Winning of the Great War at Sea. London:Jonathan Cape.