It is difficult to differentiate myth from reality when we speak of the Cathars. We know them, basically, from outside sources, since their word was diluted in the persecution. Thus, his image comes to us through inquisitorial sources and, above all, through the romanticized and fictionalized image created in the 19th century, with the History of the Albigensians Napoleon Peyrat. In fact, not even these people called themselves Cathars (from the Greek katharos , pure), nor Albigensian (referring to the city of Albi, which housed one of the main Churches), nor "perfect". They called themselves “good men” and “good women”, or “good Christians”. Or Christians, to dry. Even in the denomination, their self-perception is diluted and they are placed in otherness. Within this relative darkness, it is always more difficult to approach the history of women, in a situation of social subordination and relative invisibility.

Cathar women and Catholic women

We do know, however, that Cathar women they had a particularly relevant position within their communities, much more egalitarian than those that were being created around Catholic doctrine. The "perfect", like their male peers, could give the consolamentum (the only sacrament they admitted), lead prayers, bless believers or preach. The latter, freedom of speech, must have been very surprising at the time, due to the difference with orthodox doctrines, which condemned women to silence and subordination.

As an example, it is worth mentioning that, in 1207, a Cathar woman, sometimes identified with Esclermonde de Foix , intervened in a public controversy between Cathars and Christians. The Catholic monk told her to go back to her spinning wheel, assuring her that her place was not in a public meeting. In Catholicism, although women were granted the power to write, which allowed greater male control of the result, the word had always been vetoed. The latter is much more free, uncontrollable and accessible, which made it much more dangerous. Furthermore, the reference to the "distaff" as a symbol of domesticity is enormously significant.

The “good women” they appear to be more sedentary than their male counterparts, and made fewer trips to preach, although in the last years of the persecution, preachers often traveled in mixed pairs, posing as married couples to avoid the suspicion of inquisitors. However, they did create more powerful solidarity networks than men, by grouping together in community homes. In them, in addition to doing manual work and living with the population (unlike the nuns and monks, who isolated themselves from the lay population), they cared for the sick, welcomed widows, accommodated travelers or helped the poorest people in the community.

In addition, there was no concept of closure, so not only did they come and go, but many girls were educated who would later become wives and mothers. In this way, the ties between relatives and friends influenced all the families in the area. The Catholics, then, were not only assisted by the Cathars, but many of their relatives converted or lived in these homes. This system and warp of homes and communities allowed preachers to move freely and with a certain material security, as well as creating a very powerful sense of identity. They also functioned as socialization and conversion tools, providing a safe place to discuss, teach, listen to itinerant preachers, and meet.

In this situation it had an important influence, probably , the special economic situation of women in Languedoc . The customary law of the area allowed them to inherit, make a will and a certain ability to manage their property, which placed them in a more economically consolidated position than that of women in other areas. That also meant a certain agency when founding homes or maintaining charities, as well as a certain social authority.

Thus, some of the best-known "good women" or believers, such as Blanche de Laurac, Esclarmonde de Foix or Geralda de Lavaur , came from noble families and made important expenses in their communities. Geralda also took charge of defending her city against the Crusaders, which earned her the chance to end up being thrown into a well and stoned to death. Likewise, to discredit her even after her death, the accusation was spread that she had had incestuous relations with her brother.

The Crusader attack on these women, known for their social actions and their help to the most disadvantaged, contributed, together with the mass executions of the civilian population (in places like Béziers or Marmande) and the destruction of crops, because they were not exactly well received. In this way, instead of creating hatred towards heretics, a certain protection of them and a greater sense of community and identity were promoted.

A more egalitarian society?

It should be noted that there was also a strong spiritual component in this air of relative equality. For the Cathars, what is truly divine is the spirit, while matter is impregnated with evil and contamination. Thus, the body, and with it sex, is a mere accident, something to overcome and leave behind. The renunciation of the body, through asceticism, allowed men and women to be equal. From these ideas also comes the renunciation of sexuality or the consumption of meat, creating a spirituality far removed from bodily materiality. The same thing happened with the renunciation of having symbols, images or relics, as well as temples. This, again, reverted to a special importance of the houses and the female presence in the creation of meeting spaces.

Something similar had happened in early Christianity, in which the Desert Mothers and the martyrs were respected under the figure of the mulier virilis , the one that overcame the alleged weaknesses of her sex by giving up the body, sexuality and pleasure, depriving herself of food and a family life. This made her words charged with divinity and authority, placing them above even many of her male peers. Similarly, many of the early churches were domestic, being led and provided space by women.

That is not to say that there was real and complete equality among “good Christians”. Women, especially believers who had not received the consolamentum , were still subject to their male relatives and many Cathars participated, in daily life, in the prejudices and misogyny of the time, accusing women, in addition, of being perpetuators of the evil matter, as well as elements of temptation or perdition. Many noble believers would not bow down to a "good woman", even though she was "perfect" and they were mere believers, if she belonged to a lower stratum. However, the contrast with Catholic doctrines was remarkable and noticeable.

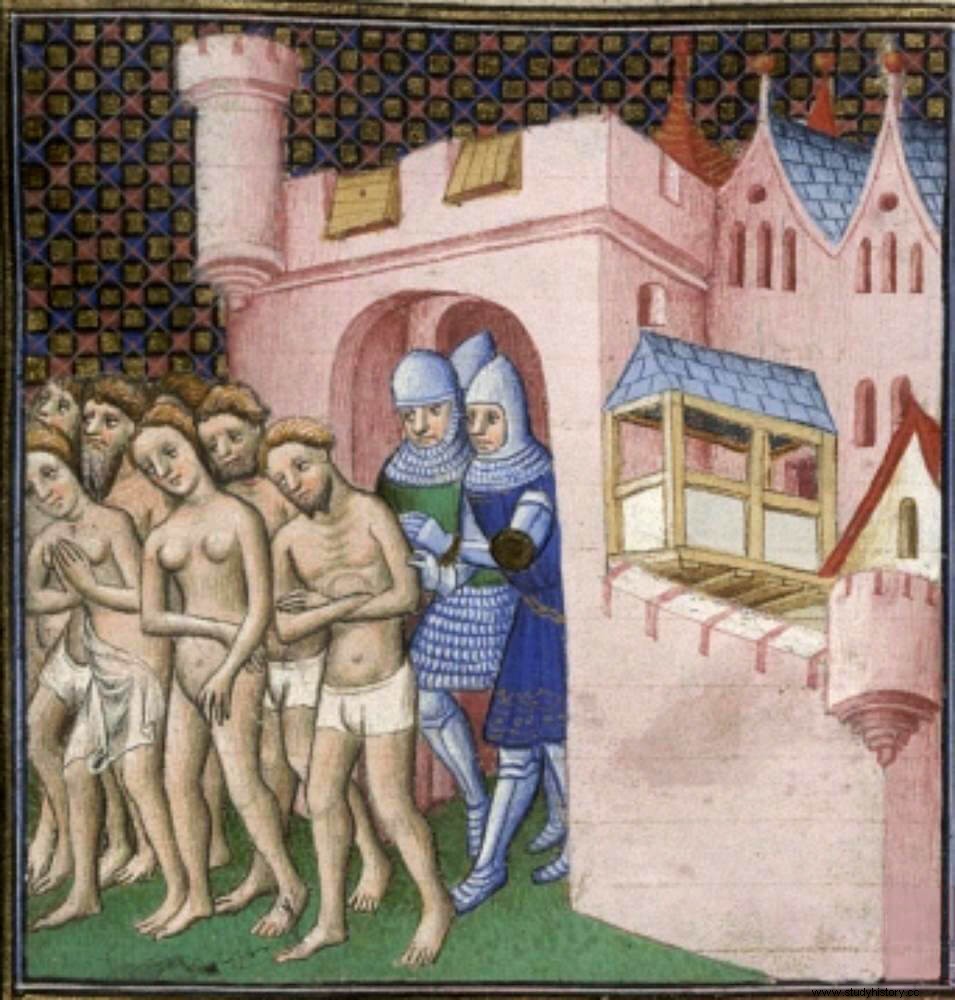

The "good women" also faced the Inquisition and to death on equal terms, being equally burned at the stake that had so recently appeared in Western Christendom. This homogeneity also affected the repression of the civilian population. Many of the cities assaulted by the crusaders ended with the entire population burned or put to the knife, or, in the best of cases, expelled with what they were wearing (as in the case of Carcassonne).

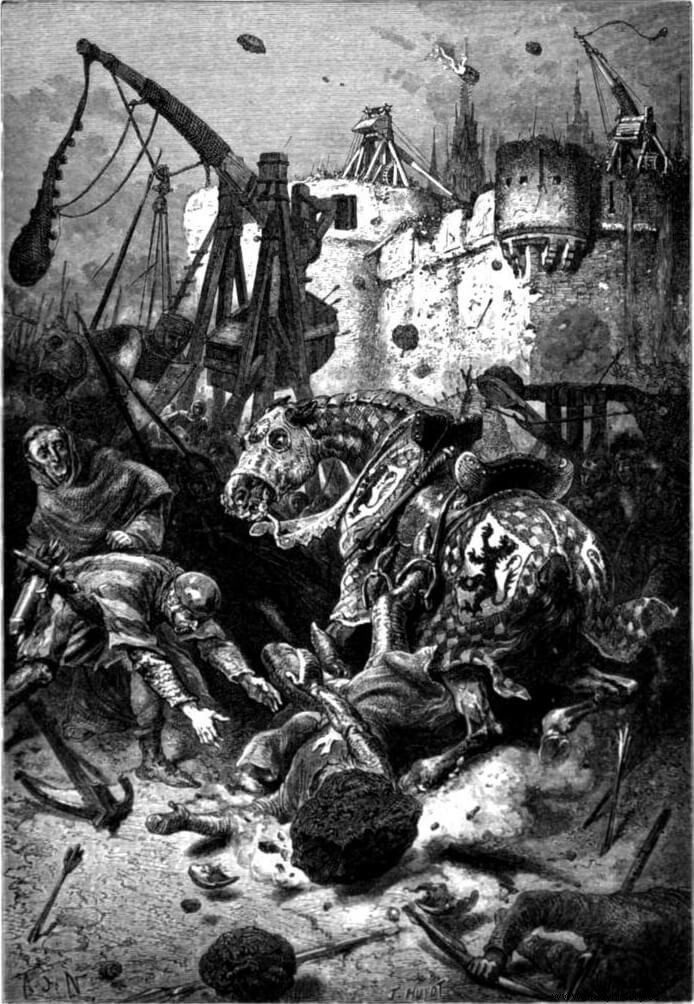

Interestingly, history counts (though we don't know how much there is legend) that Simón de Montfort scourge of the Cathars and the nobility that supported them, the cause of so many massacres of civilians, regardless of sex or age, died precisely at the hands of women (see «The most fearsome sieges in Desperta Ferro Antigua y mediaeval #56:The Crusade Against the Cathars (I) ). In the siege of Tolosa it would be a catapult handled by a group of women from the city, the one that would shoot the stone that ended up hitting him in the head. Perhaps it was just a repetition, as in so many other stories, of the symbol of desperate and brave female action in sieges, but the myth is too complete not to tell.

Bibliography

Brenon, A. (2001):Cathar women. Barcelona:Tikal.

Brenon, A (1989):Le vraie visage du catharisme. Balma:Ed. Loubatières.

O’Shea, S. (2002):The Cathars:the perfect heresy. Barcelona:Vergara.

Ruiz, T. (1994):“The Cathars:a reflection on orality and writing”, DUODA Journal of Feminist Studies , 7, p. 119-124.