The arrival in government of the July 26 Movement ( see Awake Ferro Contemporary #31:The Cuban Revolution ) was conditioned by two reasons:firstly by the imposition of arms against its enemy, and secondly by the political ambiguity wielded by a large part of its leaders, including Fidel Castro himself. . The United States supported in a timely and important way the guerrilla campaign led by the Castros against the dictator Fulgencio Batista . Castro's ambiguity regarding his policies earned him a lot of sympathy and support, since there was still no trace of a Marxist discourse.

The new government began to enact laws to regulate the life of the country with profound reforms, especially in the economic framework. This undoubtedly fully affected the United States, which saw how their businesses and plantations were first seized and then expropriated. Added to all this was the fact that sugar was no longer purchased under US conditions to be exported under exclusively Cuban terms.

On the other hand, the overthrow of Batista was not satisfactory for all Cubans of that time, something that is visible in the large number of exiles who left the island before the arrival of the revolutionary hosts. This group of exiles, the vast majority of whom were former police and army officials and members of the Batista government, took refuge in Miami (United States). From this geographical point close to Cuba, the creation of the first fully anti-Castro movements has already begun.

The subsequent agreements with the Soviet Union they definitively convinced the United States that the new Cuba was a danger to its global strategy. In the Oval Office of the White House, an invasion of the island began to be plotted, for which the exiled residents of Miami would be used as military forces, which in the end would give a vision more of "liberation" than of an actual invasion. bliss.

The approach and the 2506 brigade

The material resources of the United States and the human strength of Cuban exiles would be the perfect formula to overthrow the new Cuban revolutionary government. The approach of the invasion took several turns of the screw until finally an organized deployment was presented. Initially, what would be Brigade 2506 It was no more than a few dozen former Batista army officers; recruitment began between the months of April and May 1960[1]. These dozens increased in number until they became a fighting force to be reckoned with, made up of several battalions. Sources currently tell us of an approximate number of 1,200 or 1,500 men integrated into Brigade 2506

Brigade 2506 consisted of seven battalions. The first of them was made up of paratroopers who would be launched to capture key points, nearby centrals. The second, fifth and sixth battalions were infantry units. The third battalion was mechanized. The brigade members were given trucks and also five M41 armored cars. The fourth battalion was a heavy weapons unit. Finally, the seventh battalion would remain in reserve and would not move from its base in Guatemala, awaiting the development of events.

The deployment that was initially thought was to introduce small counterrevolutionary groups in the mountains Cuban, in the style of what Fidel Castro had done. For this, the brigade was sent to Guatemala where it was trained in survival techniques and guerrilla warfare, this training lasted about eight weeks[2]. At the end of 1960 the strategic conception was changed again. American advisers abandoned this type of training to continue with conventional techniques. Cuban exiles would be trained in conventional amphibious landing techniques.

Of course weapons and material would be delivered by the United States . Curiously, when the invasion was being planned, the United States did not want it to be known that those resources were theirs, so they told the exiles that everything had been financed by an anonymous Cuban millionaire. However, the soldiers of Brigade 2506 were quick to refer to this anonymous millionaire as “Uncle Sam”[3]. The weapons were varied and all came from military surplus from the Second World War.

Finally, the 2506 Brigade would have the support of the so-called Liberation Air Force , a small air force made up of a small squadron of B-26 bombers. The Cuban pilots were mostly students with less than 100 flight hours. However, some pilots were recruited from some civilian airlines and had briefly passed through Batista's air force[4]. Once the preparations were finished, the anti-Castro military force would be transferred to the Bay of Pigs in five ships bought by the CIA from a Cuban company.

The Bay of Pigs Invasion

The Bay of Pigs invasion was carried out in four phases. Operations began on April 14, 1961. At first, a small force of 160 soldiers had to enter from the Guantánamo area to try to divert Castro's forces to the east. When they were near the coast they saw the light that seemed to be emitted by the cigarettes of militia groups. Seeing this they turned around and aborted the mission. That same day the transports that carried the brigade and the US destroyers that protected them took up positions in front of the beaches of Girón. The men on the boats are not told where to disembark until they are out at sea.

April 15 starts to air operations . The squadron of B-26 bombers painted in the color of the Cuban air force begins bombing targets on the island. The first of these objectives was to eliminate Castro's small air force. This could not be carried out since the revolutionary government had hidden and camouflaged the aircraft throughout the island. Damage from the attack was relatively little, and the Cuban air force was not destroyed.[5] In any case, the Cuban anti-aircraft batteries were very active, although they did not manage to shoot down any enemy aircraft. The bombs that fell that day at dawn woke up Commander Ernesto "Che" Guevara, who declared:"the sons of bitches are attacking us at last"[6].

On April 16, while the bombing was still going on, there were a series of diplomatic reactions . The Cubans accused the Americans at the UN of being behind the support they were receiving for the attack. That day, President John F. Kennedy also refused to intervene definitively in the invasion that was taking place. Kennedy preferred to wait to see how events unfolded. On the same day, the leader of the revolution, Fidel Castro, made some very important declarations. For the first time since 1959, Castro revealed the socialist nature of the revolution.

The next day (April 17) the landing of Brigade 2506 began. It was carried out as planned, although very soon the units were overwhelmed by the new forces Cuban, made up mostly of militiamen equipped with Czech, Soviet and Belgian material. The brigadistas landed a large amount of weapons on the beach, including several M41 armored cars that put a Cuban T-34/85 out of action. On the day of landing, the parachute battalion was also launched in C-47 transports. Together, the unit managed to take several small towns. Although confusion reigned for a few hours, Fidel Castro managed to gather means to block the brigade's penetration. The revolutionaries scored a victory against the Río Escondido ship that was hit by a Sea Fury[7].

Throughout April 18, brigadistas and militiamen did not stop fighting each other. Although Brigade 2506 had mortars, Castro's forces attacked the beachhead with M30 122mm artillery pieces. Without American help the invaders began to lose heart. Although it is true that that same day they managed to repel Castroist counterattacks, they were unable to advance beyond their positions. Apart from this, the militias and the regular army were becoming more and more organized and advancing towards the beach. The paratroopers of the first battalion were the ones who resisted the most enemy attacks. Apart from the heroism shown by both sides in the fighting, the brigade was left to its own devices by the US government, as Kennedy refused to meddle any further in the operation.

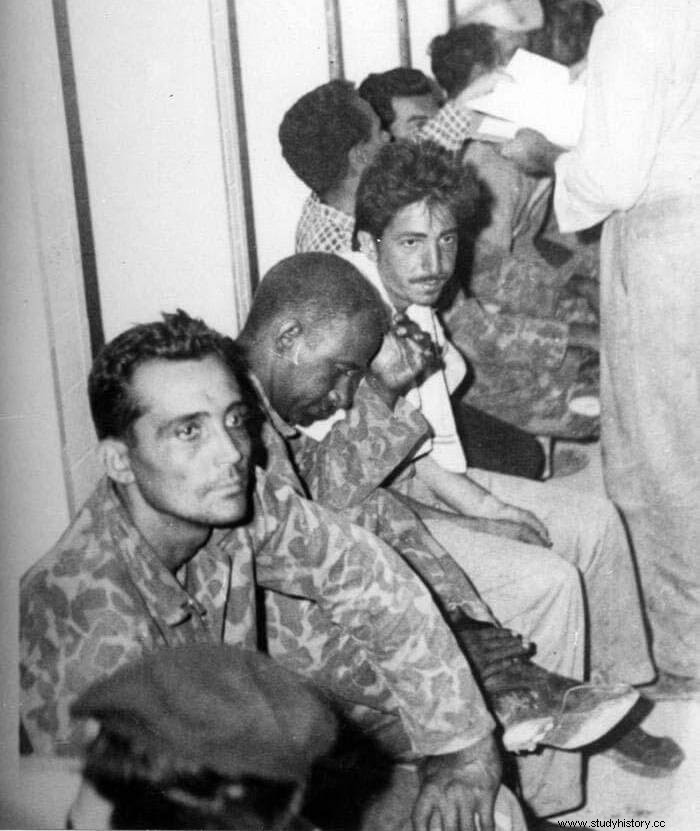

On April 19, the counterrevolutionaries finally surrendered in the small area they controlled. The lack of air support and provisioning condemned the men from Playa Girón, who were already surrounded by a much higher number of government troops. During the early hours of the morning, the various resistance groups surrendered to the Cuban army. The great majority of the members of Brigade 2506 were taken prisoner. They were taken to Havana where the treatment received was generally good.

Consequences

The military victory at Playa Girón was in turn a great propaganda and political victory for the revolutionary regime led by Fidel Castro. At the propaganda level, it was announced that Girón had been the first defeat of North American imperialism. On a political level, the anti-Castro collaboration with the invaders allowed the July 26 Movement to shake off any opposition, as numerous arrests were ordered. It is true that later many opponents were released, but the heads of the movements had been severed.

The more than 1000 prisoners were later exchanged for the payment of a considerable amount of money, especially for the leaders of the expedition, and medical supplies. However, until the late 1960s there were small resistance groups in the country's mountains. In numerical terms, the losses in the Battle of the Bay of Pigs were not very high. The Cuban army lost 161 men[8] and had about 300 wounded. Brigade 2506 lost 110 or 120 expeditionaries, in addition to several hundred wounded.

Bibliography

- Anderson, J. Lee (2013):Che Guevara. A revolutionary life . Barcelona:Anagram. Pg. 479-482.

- De Quesada, A. (2009):The Bay of Pigs, Cuba 1961 . London:Osprey Publishing.

- Rodríguez, Juan C. (2005):Girón, the inevitable battle. The most colossal CIA operation against Fidel Castro . Havana:Ed. Capitan San Luis.

- Thomas, H. (1974):Cuba the struggle for freedom 1762-1970 , Volume III “The Socialist Republic 1959-1970 ”. Barcelona:Grijalbo. Pg. 1729-1751.

Notes

[1] Rodríguez, 2005, p. 49.

[2] Ibid.

[3] De Quesada, 2009, p. 9.

[4] Ibid., p. 11.

[5] Rodríguez, 2005, p. 236.

[6] Anderson, 2014, p. 480.

[7] Thomas, 1974, p. 1734.

[8] De Quesada, 2009, p. 46.