In January 1704 Philip V ratified the order to that the Tercios reorganize themselves into regiments (see "From Tercios to Regiments" in Desperta Ferro Especiales XIX:The Tercios (VI) 1660-1704 ), in other words, that the Hispanic military system became a carbon copy of the French and that, during the transformation, the cursus honorum was forgotten. that those had worked since the reign of Carlos V. Much has been debated and is debated about the reasons that led the first Bourbon monarch to make this decision:reduce the costs that each unit entailed, have a number of officers more in line with the needs of the moment, obtaining a structure that married the prevailing military theories in the early years of the eighteenth century, etc.

These, among others, could be called objective causes, but the feelings of a person must also be taken into account when making a resolution, since it is fully entering the field of subjectivity, and more so if we are talking about a character as complex as Felipe V. The Tercios had been the enemy to beat by the Bourbon dynasty from the end of the 16th century –when Henry IV faced the Army of Flanders under the command of Alexander Farnese– until the last measure of the following century –the warrior reign of Louis XIV–. During all this time, they had proved to be the backbone of the Habsburgs' military pre-eminence in Madrid and, although the French troops managed to defeat them on occasion, they had maintained their military reputation by continually displaying adaptability and resilience – I don't want to use the term resilience, originally from English and so in vogue lately–, so it is easy to assume that the new king would be delighted to finish off these units with a –never better said– stroke of the pen.

Bourbonic Spain and the disappearance of the Tercios

And if Felipe V did not show any fondness for them, the courtiers and soldiers in his service had even less, looking for a place in the new order that was born. Therefore, if objective and subjective reasons are put together, it is easy to understand that in the blink of an eye the services rendered by the Tercios to the House of Austria -criticized incessantly by the new dynasty and its supporters in order to more vehemently legitimize his establishment on the throne of the Monarchy– fell into the most terrible punishment in history:oblivion.

During the 18th century they were not a topic of interest for Spanish historiography , who more than once ignored them, even when making bibliographic compendiums despite the huge number of books on the art of war published by Spanish authors or from other territories of the Hispanic Monarchy between the 16th and 17th centuries, and who had militated under the banners of the Habsburgs. An example of what was said was the work published by Vicente García de la Huerta, Spanish Military Library (Madrid, 1760). In the previous speech on the usefulness of the art of war, he only cites historical events of antiquity, especially carried out by Caesar, but at no time does he remember the acts carried out by the Tercios that occurred one or two centuries earlier.

From a military point of view, his teachings were forgotten in a new army that, as I have already pointed out, emerged in imitation of the French model. If during the 1720s and 1730s they were on the lips of some military men – those who had served as field marshals or the colonels who did so at that time – it was simply to ensure that the seniority of the new regiments was recognized after inheriting it. of the Tercios from which the first ones had been created; a matter of honor, primacy, privileges and, of course, assets. As a result, the regiment that managed to prove that it was heir to the cursus honorum of a Third and that he had served the longest, he was able to achieve a certain pre-eminence over others.

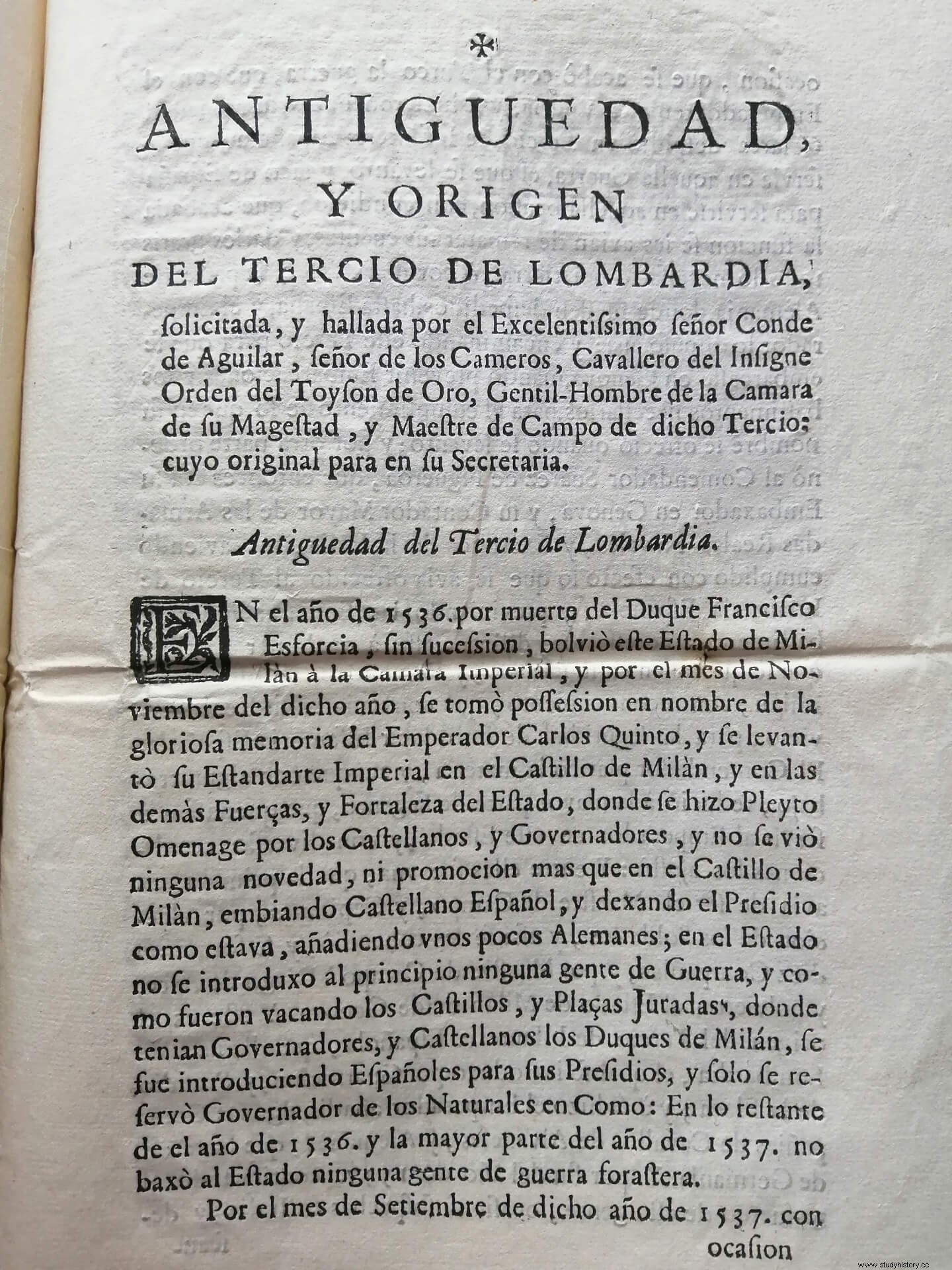

An example of the tools that were used to corroborate the statements made was the printed Antiquity and origin of the Third of Lombardy (s.l., s.a. [c. 1720]), written by Íñigo de la Cruz Manrique de Lara Arellano y Mendoza, Count of Aguilar de Inestrillas, in which, based on the use of different histories and writings, the author managed to demonstrate that the Tercio that had been under his command long ago it was one of the oldest, which is why the Lombardy Regiment must have had a certain prominence over the rest. It is not surprising that this struggle – a faithful reflection of the Spanish society of the Old Regime – finally had to be nipped in the bud by the Crown itself. Thus, Juan Antonio Samaniego published the Dissertation on the antiquity of the infantry, cavalry, and dragoon regiments of Spain (Madrid, 1738) where the issue of seniority inherited by each unit in the service of the Bourbons was more or less resolved.

However, it was not until more than a century later when the Earl of Clonard , at that time lieutenant general, resumed the study of the Tercios in his monumental Organic history of Spanish infantry and cavalry weapons from the creation of the permanent army to the present day (Madrid, 1851-1859), published in sixteen volumes. The historiographical conception of the work was similar to the one used by Samaniego, since in numerous cases it went back to the time of service of the regiments to that of the Tercios of which, it was assumed, they were heirs. It was this author who put into vogue the use of nicknames such as "the Brake", "the Terror", "the Bloody"... despite the fact that none of the Austrian units had been called that. In reality, the name normally came from the place where he had served –Naples, Flanders, Savoy…–, from the name of his field master –Diego Mexía, Count of Tyrone, Guillermo Verdugo…–, or, in the final stretch of the 17th century, based on the place where they had been taken or the color of their uniforms –Toledo or the Old Blues, Jaén or the Silvers, León or the New Yellows…–.

Regarding the study of the conflicts in which they were immersed, the 19th century meant a resurgence of their fame thanks to Positivist History. Of the one hundred and thirteen volumes of the Collection of unpublished documents for the History of Spain, (Madrid, 1842-1895) many collected documentation related to them, while authors such as Francisco Barado –Museo Militar. History of the Spanish Army (Barcelona, 1889)–, Antonio Cánovas del Castillo –Studies on the reign of Philip IV (Madrid, 1888)–, Antonio Rodríguez Villa –Ambrosio Spínola, first Marquis of los Balbases. Biographical essay (Madrid, 1905)–, Julián Suárez Inclán –War of annexation in Portugal during the reign of Philip II (Madrid, 1897-1898)– or reissues of texts from the 16th or 17th century such as those by Martín García Cerezeda –Treatise on the campaigns and other events of the armies of Emperor Charles V in Italy, France, Austria, Barbary and Greece , from 1521 to 1545 (Madrid, 1873-1876)–, Diego de Villalobos y Benavides –Comments on things that happened in the Netherlands of Flanders from 1594 to 1598 (Madrid, 1876)– or the thirteen annual reports written by Jean Vincart between 1636 and 1650 –published in various collections–, made the Tercios return from the limbo in which they had been plunged.

However, what could have been the germ of a series of studies on those units came to nothing from the historiographical point of view. The end of the 19th century marked the swan song of the Spanish colonial empire, the much talked about decadence became clear and its supposed origin –the Austrian dynasty, its armies and its wars– were left aside. Other difficulties beset Spain. Interestingly, a new colonial war for control of the Moroccan Protectorate led to the creation in 1920 of the Tercio de Extranjeros –or Spanish Legion– by the infantry lieutenant colonel Millán-Astray, who was inspired by them to give the new unit a spirit of the body. Its emblem is made up of three of the weapons used by the infantrymen of the 16th century –the halberd, the crossbow and the arquebus–, while the scripts on some flags represent some motifs from the same period –that of the 2nd century the coat of arms of the Emperor Charles V, that of the IVth the Christ of Lepanto, that of the Vth the coat of arms of the Great Captain, that of the VIth that of the Duke of Alba–; in addition, the legion band uses drums copied from those used by those. It is currently made up of Tercios whose names correspond to the great soldiers of that century –Great Captain, Duke of Alba, Juan de Austria and Alejandro Farnese–. In this way the Spanish Army, through a very special Corps, recovered part of its past.

From oblivion to today

From an academic point of view, for much of the 20th century no studies were dedicated to the subject in Spain. However, with the publication of the works of Geoffrey Parker –The Army of Flanders and the Spanish Road, 1567-1659 (Madrid, 1976)– and René Quatrefages –The Spanish Tercios, 1567-1577 (Madrid, 1979)– and, although it did not deal directly with Tercios and the title chosen by the Spanish publisher deformed the English original, I would add that of I. A.A. Thompson –War and decline:government and administration in Austrian Spain, 1560-1620 (Barcelona, 1981)–, the panorama turned 180 degrees. It is ironic that two Englishmen and a Frenchman were the ones who revitalized his study, thanks to them the Spanish university once again became interested in the military world of the Golden Age.

Still, it is frustrating to see that there are those who believe that there is nothing more to say about Thirds. Parker, Quatrefages and Thompson only explored a tiny part of an immense world that remains unknown in Spanish, Italian and Belgian archives, but also in Austrian, French, British, Dutch, etc. It must be recognized that they raised some strong pillars but they also erred in some of their statements or points of view. For example, Parker did not realize that the great riots that occurred between the 1570s and 1609 did not occur again, since the financial system of the Army of Flanders improved significantly during the first half of the 17th century. In addition, the first two works focused on the northern battlefield, although the Tercios served throughout Europe -especially Italy, France and Spain- and the Oceans.

The 1999 publication of From Pavia to Rocroi (reissued in 2017 by Desperta Ferro Ediciones), by Julio Albi de la Cuesta , was a turning point, and today, thanks to the efforts of a not very large group of military historians –among whom I have the honor to include myself–, studies on these units are gradually multiplying. Despite this, there is still a long way to go to know all its aspects, although, happily, less and less. And fundamental in the journey has been the publication of the six specials dedicated to the Tercios by Desperta Ferro Ediciones – the first, dedicated to the 16th century, appeared in 2014, was directed by the person who writes these lines – which have served to that the general public can be aware of the latest research, since no matter how much progress is made, if they are not transmitted to society, they are of no use.