William Boyd (Bill, as he liked to be called) Kennedy Shaw , in his 1945 work dedicated to the LRDG , his experience in the desert, a territory where deprivation was the order of the day but which, however, became a scenario dominated by the men of this unit, fundamentally for exploration, although it would also participate in direct actions against the enemy, as Saul Kelly tells us in The Lost Oasis. Almásy, Zerzura and the desert war .

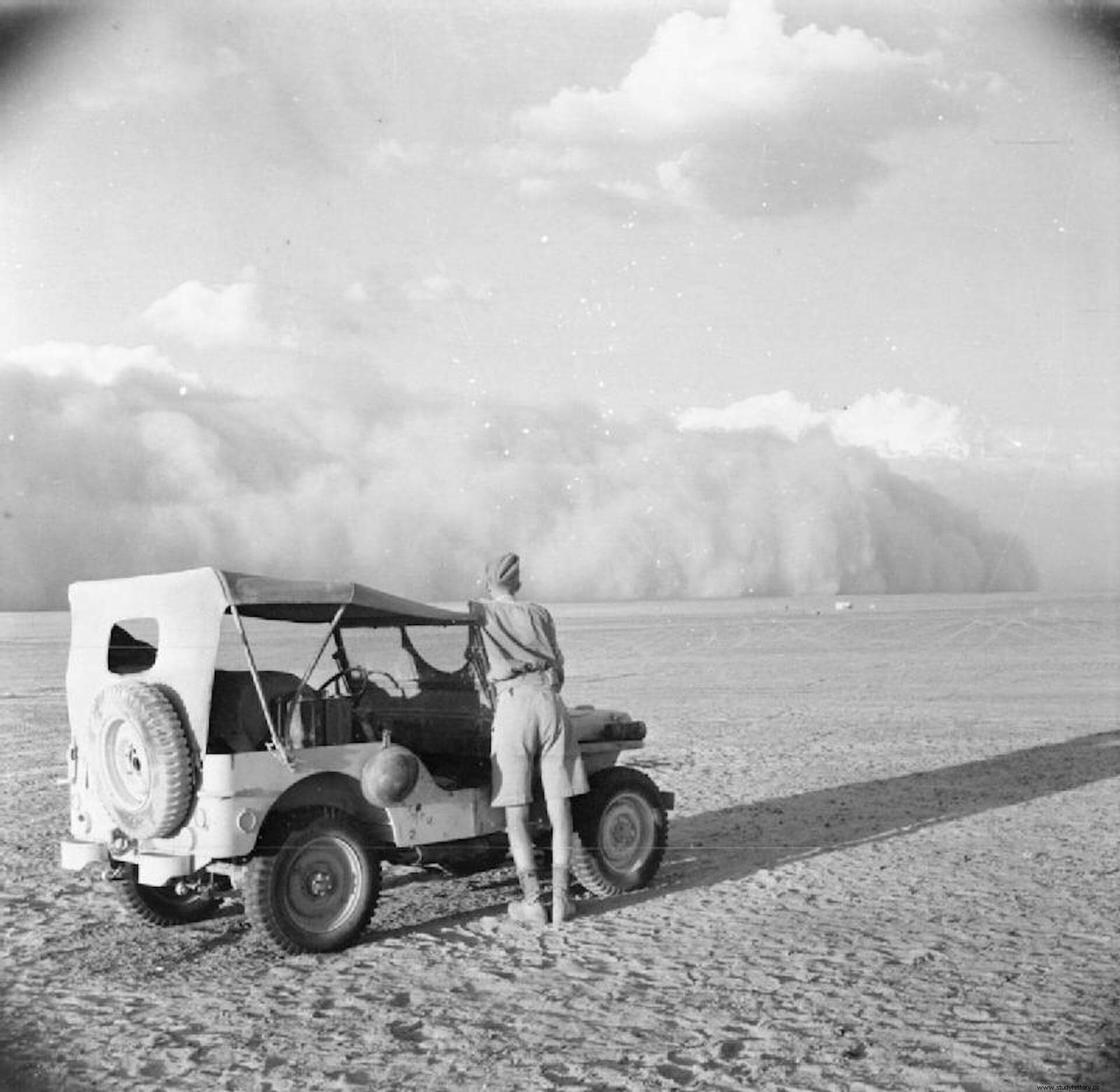

When one thinks of the desert, heat and thirst immediately come to mind. There is something false in the first of these deprivations, for the nights can be very cold (which is not necessarily a relief either), and thirst can be quenched with adequate supplies of water. For Kennedy Shaw the worst was the Ghibli .

Events like these could last for days and become a terrible test for the men of the LRDG, although our author will also come to recognize that these phenomena were much worse on the coast, where the The passage of tens of thousands of soldiers had turned the ground into a constant cloud of dust, while in the desert “only” it was sand that riddled everything, and although the winds could blow up to 100 km/h, it They were built at ground level, so it was always possible to move around.

Despite everything, training the future fighters of the LRDG to fulfill their missions in these circumstances was never complex since many already had the characteristics and knowledge of soldiers and, furthermore, there was no time. The New Zealanders were only going to make two trips, along with Bagnold , before being considered fit for service; The Guards, for their part, would receive ten days of training, two of which were to be spent in the desert itself, near el-Fayoum, with Commander Pat Clayton . One of the noncommissioned officers of Patrol S, formed with Rhodesian soldiers in January 1941, will remember:

Spirit of survival

Among the techniques that were learned in the LRDG, the fundamental thing was to survive in the desert , for which it was important to learn to conserve water (although once the discipline was acquired, each man could consume his ration as he saw fit) and to take refuge. It was also essential to know how to navigate, since men could easily get lost, or be abandoned. Four men were to specially apply these techniques:soldiers Moore, Easton, Winchester and Tighe , left for dead on January 31 after being attacked by the T Patrol (New Zealand), to which they belonged. The unit, commanded by Pat Clayton and made up of eleven cars, more than thirty men and four Breda 20mm guns, was surprised by the Italians at Jabal Sherif, south of Kufra, and by the time the fighting was over Clayton had been wounded and captured, the remnants of the force were hurriedly retreating south, leaving several vehicles on the ground, and the four men mentioned above had been left behind.

On February 1, they began the march to the south after the taxiing of their patrol vehicles. On day 4, after walking for hours with little sleep due to the low temperatures, Tighe began to show signs of fatigue, which they attributed to the after-effects of an old operation. That same day they ate his last substantial meal, a jar of canned lentils that had been discarded days before on the way out, and now proved providential. On the 5th they had to leave behind Tighe, who couldn't keep up, after leaving him his share of water. On the 6th they were surprised by a sandstorm, despite which the marks on the track, which was very busy, did not completely disappear. That same day Moore, Easton and Winchester arrived at Sarra, where there was a well which has been blocked up by the Italians, wood to start a fire and motor oil, with which they rubbed their feet. There was no food.

On day 7 it was Tighe who arrived at Sarra where he, unable to continue, he stopped for good. On the 9th, a French patrol arrived in the town and met the New Zealander, who informed them that three others were ahead of him. However, night was falling and it was not possible to follow the tracks, so the Gauls stopped. They did not know that during the day one of their planes had located Moore and Winchester (Easton had stayed behind), dropping food and water on them. However, the soldiers had been unable to find the first, and of the second, lost the cap of the container, there were barely a couple of drinks left.

On February 10 the French began the search. They would soon find Easton, who had drifted west, lying on the ground but alive, though he was to die a few hours later. Shortly after, 100 km south of Sarra, they located Winchester, who had also been unable to continue, delirious but able to stand. Ultimately, they would have to travel another 16 km to find Moore, who had by then traveled almost 340 km from the scene of the incident and looked capable of reaching the French outpost of Tekro (130 km further in Chad). , where there was water, and he was not going to hesitate to show his frustration at having been "rescued" before he got it.

Moore's tenacity undoubtedly squared with Kennedy Shaw's assessment of the New Zealanders of the LRDG, men who

The stinger of the LRDG

In any case, it is certain that neither the British nor Neither the Rhodesians nor other LRDG contingents detracted from the courage and tenacity of the New Zealanders. Such men as these stormed Murzuk on January 11, 1941, razed Cyrenaica in March and April, repeatedly disrupted the Axis rearguard, especially during Operation Crusader, spied on their movements, and carried out attacks on their airfields (Operation Caravan, against the Barce aerodrome, in September 1942) and its ports, such as Bengasi (Operation Bigamy, the same month) and Tobruk (Operation Agreement on the 13-14 of the same month).

The end of the Africa campaign did not mean the dissolution of the LRDG, but its transfer to the Aegean, where the patrolmen would exchange their trucks and cars for boats and canoes to move between the islands, and where many more would lose their lives in a strange scenario, for which they had certainly not been trained.